Click here to read the original post.

You know, it’s kind of wild how things cycle back around, isn’t it?

It really is. What’s on your mind?

Well, beef tallow, for instance. I mean, I remember it being completely uh demonized, right? I mean, because of all the saturated fat stuff.

Oh, absolutely. Persona non grata in the kitchen for decades.

And now suddenly it feels like it’s popping up everywhere again. People are cooking with it, using it on their skin. I’ve even seen like biohackers talking it up.

Yeah, it’s a fascinating resurgence. And the materials you sent over exploring this trend. They really pose a good question which is is this comeback based on you know new science. Or is it more about maybe nostalgia like an ancestral wisdom kind of thing without looking hard at the evidence.

Right. It feels like part of that bigger trend maybe questioning the usual advice looking back to tradition.

Exactly. There seems to be this undercurrent of skepticism towards established health guidelines and the sources you shared really map that out. Tallow wasn’t always the bad guy. It used to be a kitchen staple. Right.

Totally. Think pie crusts frying. McDonald’s used it for their fries.

No way. Really?

Yeah. Up until 1990 gave them that distinctive flavor.

Wow. So what happened?

Well, starting around the 60s, research began linking saturated fats to higher cholesterol levels and you know heart disease risk.

Ah the beginning of the lowfat push.

Precisely. And there was pressure from health advocates campaigns. By 1990 companies like McDonald’s had switched over to vegetable oils.

Oh, okay. But that switch wasn’t exactly straightforward either, was it?

No, not at all. And this is where the story gets well kind of complicated. Some of those early vegetable oil replacements, the partially hydrogenated ones, they turned out to be packed with trans fats, which we later found out were even worse.

Arguably, yes, even more harmful for heart health. So, the initial solution created a whole new problem and honestly, a lot of confusion about fats that we’re still sort of dealing with.

Okay, so trans fats are mostly gone now, thankfully. But what replaced tallow then after the trans fat scare?

Mostly other vegetable oils. Canola, soybean, sunflower, corn oil, that kind of thing.

The ones often marketed as healthier. Cholesterol-free, high in polyunsaturated fats or PUFAs.

Exactly. But now you’ve got this whole counter movement, haven’t you? The anti-seed oil crowd.

Yeah, that’s definitely loud online. What’s their main argument?

Well, they often claim these oils are like ultrarocessed, unstable when you heat them, and potentially inflammatory in the body. It’s a lot to keep track of. So what does the mainstream science say about that debate? Seed oils versus saturated fats like tallow.

Okay, so the general scientific consensus based on, you know, large studies and trials is still that replacing saturated fats with polyunsaturated fats, the kind found in many vegetable oils tends to lower LDL cholesterol, the bad cholesterol, right? And lowering that is linked to a reduced risk of heart disease. So major health bodies generally consider oils like olive oil, canola, soybean oil as safe. even beneficial in moderation.

But what about the inflammation and instability claims?

There’s ongoing research into how these oils behave, especially when heated repeatedly. That’s the oxidation part, but the widespread claims you see online about seed oils being toxic, they don’t really have strong backing from clinical trials in humans.

So, the bottom line for most people is still that these vegetable oils are likely a safer bet than loading up on saturated fats

in the context of a typical Western diet. Yes. That’s generally the conclusion. They remain a safer alternative to routinely using highly saturated fats like tallow or butter for most of your cooking and fat intake.

Okay. So, if the science hasn’t drastically flipped, why is tallow making such a comeback now?

Ah, well, that’s more about culture and marketing. I think you’ve got wellness influencers promoting it as ancestral or natural and the skin care angle. Biocompatible they call it, right? Plus, chefs do genuinely like it for flavor and it’s high smoke point. It doesn’t burn. easily.

So, it cooks well at high temperatures.

Exactly. And social media just amplifies all of this, framing tallow as somehow cleaner or more real than processed seed oils.

It really taps into that desire for simpler stuff. Maybe a rejection of big food industries.

Definitely, there’s a nostalgia factor, a feeling of getting back to basics, but you know, just because something’s old or natural doesn’t automatically make it healthier. We stop doing lots of old things for good reasons.

And crucially, the fundamental science on saturated fat.

Yeah.

It hasn’t really budged, has it?

Not in its core message. The sources you looked at mentioned several big reviews of 2021, 2021, 2023.

Yeah. In major cardiology and medical journals, and they all continue to link high intakes of saturated fat with increased risk of heart disease and related mortality.

But what about that one study, I think it was 2014, that made headlines questioning the link?

Ah, yes, the Annals of Internal Medicine review. It did cause a stir. her, but it also faced significant criticism regarding its methods and conclusions. And importantly, major health organizations didn’t change the recommendations based on it.

So, the advice to limit saturated fat generally below 10% of daily calories still stands.

That’s the standard public health guideline. Yes. And those other claims you sometimes hear, tallow, fixing hormones, clearing skin, boosting mood, there’s just no rigorous scientific evidence backing those specific benefits up.

They’re most mostly anecdotal.

It does make you wonder though, why does it feel like people are more willing now to maybe disregard that scientific consensus?

That’s a huge question. It seems like health decisions are increasingly tied up with identity, maybe ideology, what fits a certain narrative and what algorithms push on social media.

Absolutely. Anecdotes from influencers spread like wildfire much faster than dense peer-reviewed studies. It feels like sometimes the story, the feeling around food becomes more powerful than the research data.

It’s like a preference for narrative over numbers.

You put it that way. And we see similar things happening elsewhere, right?

Like what?

Well, look at the resurgence of raw milk.

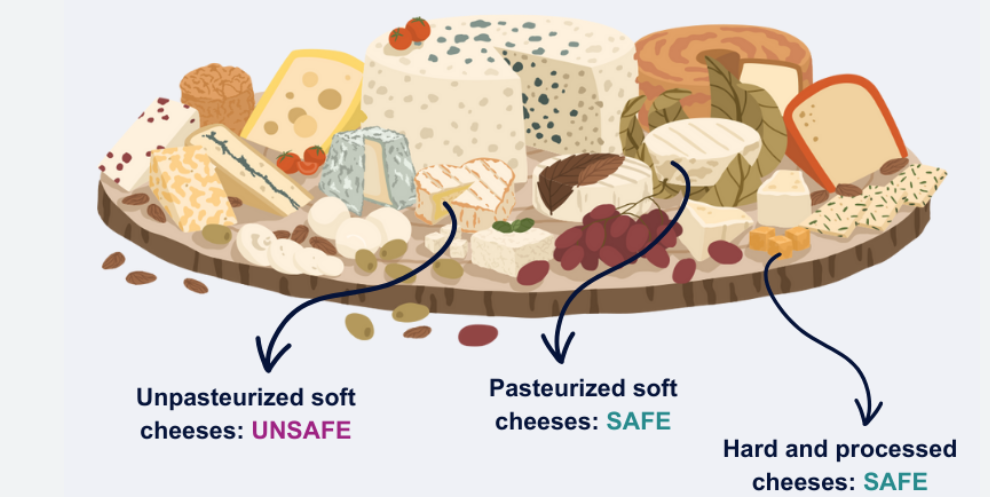

Oh, right. Similar arguments there. It’s more natural. Pasteurization destroys nutrients.

Exactly. Despite the very real documented risks of contamination, EC coli, lististeria, salmonella, things pasteurization was designed to prevent.

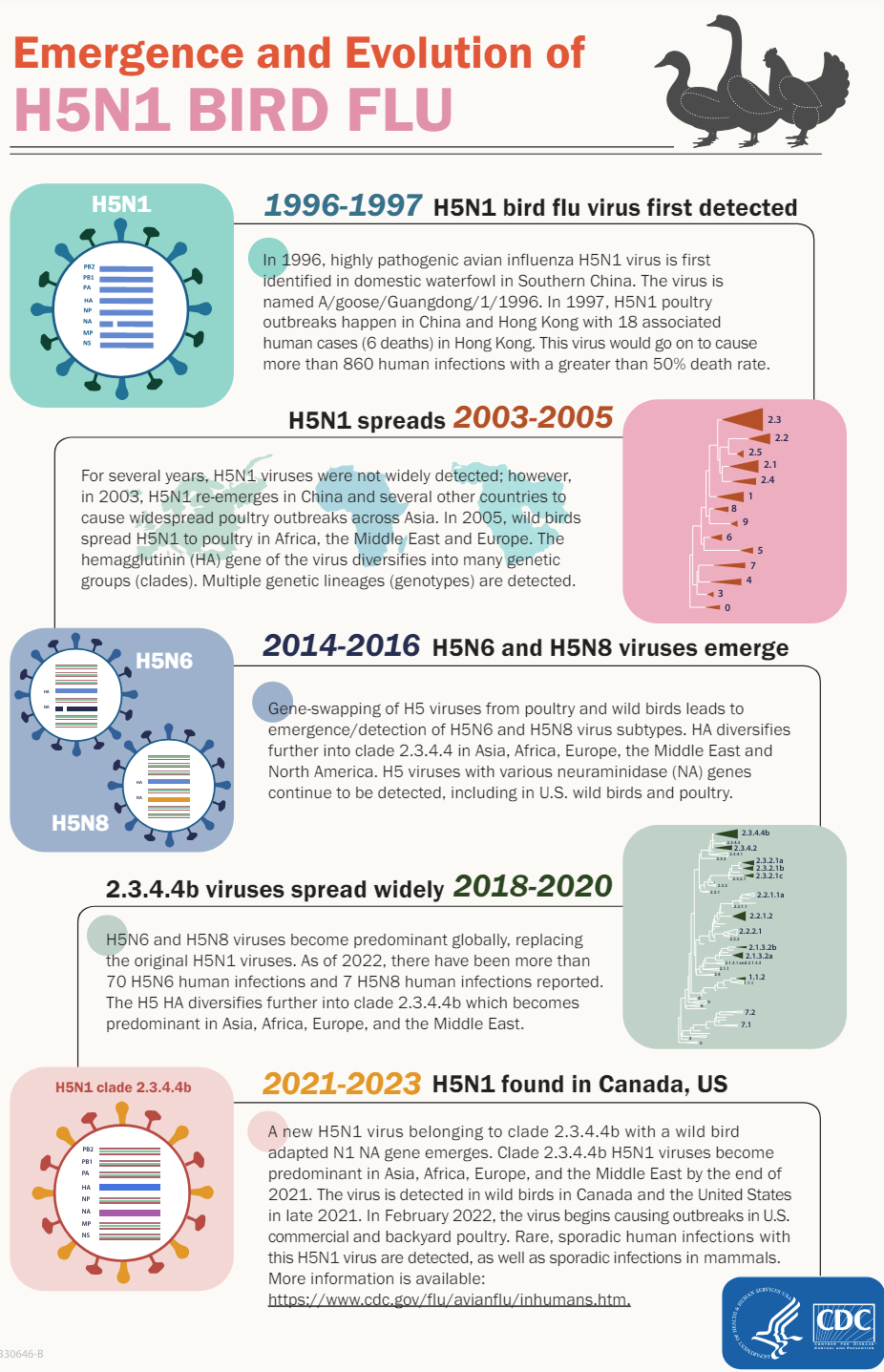

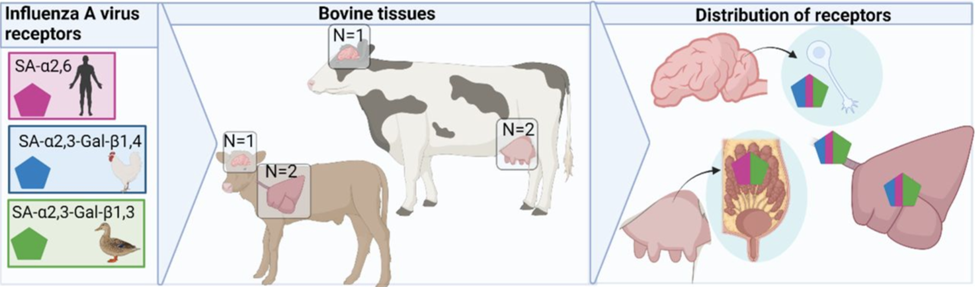

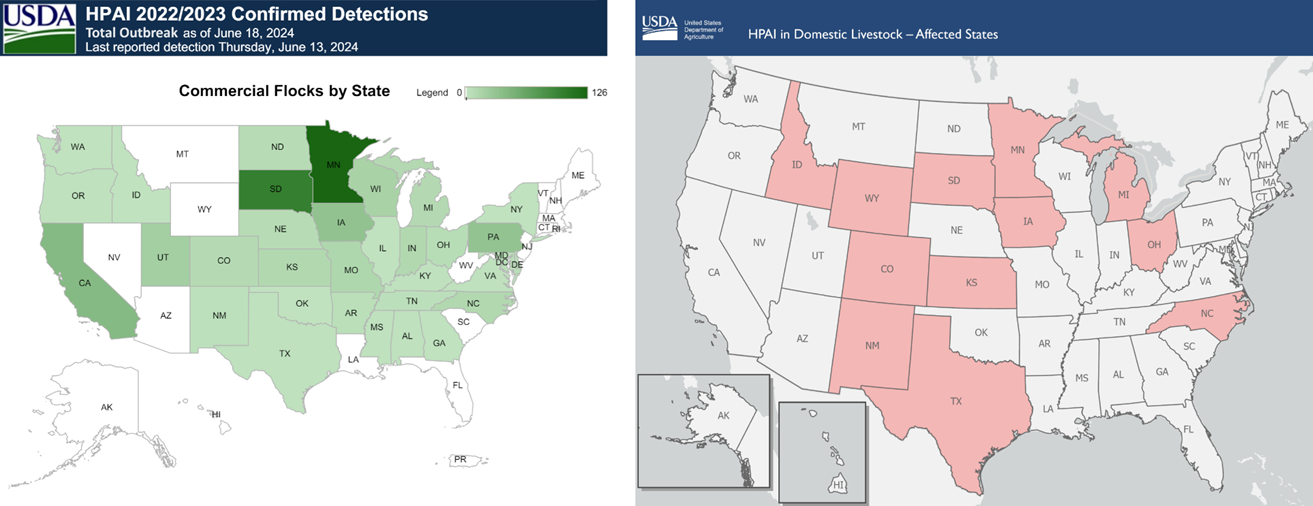

And now there’s even the worry about H5N1, the bird flu showing up in dairy herds, the FDA and CDC are warning against raw milk because of it.

Yet sales are apparently increasing in some areas driven by that same natural is better anti-establishment ethos.

It really highlights that tension, doesn’t it? The appeal of tradition versus the progress of science.

It does. It’s this sort of cultural yearning for simplicity, for a perceived lost purity.

But history isn’t always a reliable guide for health.

Precisely.

We should absolutely question our modern food system, but we also need to critically examine older practice. ices. Were they really better or just what people did before we knew more?

So, wrapping this up, the beef tallow comeback seems well less about a scientific evolution and more about culture.

I think that’s a fair assessment. It’s a cultural phenomenon, tapping into nostalgia and current anxieties about processed food much more than it is a scientifically validated health shift.

The comfort food aspect is strong, but the science on saturated fat and heart health, that story hasn’t fundamentally changed.

That remains the consistent message for major health organizations based on decades of research.

So maybe the final thought for you listening is this. When you’re making choices about food, about your health, what’s really guiding you?

Yeah. Is it the weight of the scientific evidence carefully gathered over time? Or is it more the emotional pull, the story, the allure of something that feels simpler or perhaps rebellious?

Definitely something worth chewing on as these trends continue.

This isn’t just about cooking with oil. It’s part of a broader philosophical divide. As institutional trust declines, many are turning to tradition and nature for guidance—assuming, sometimes wrongly, that these values offer more than modern science.

This isn’t just about cooking with oil. It’s part of a broader philosophical divide. As institutional trust declines, many are turning to tradition and nature for guidance—assuming, sometimes wrongly, that these values offer more than modern science.

Interested in learning more?

Interested in learning more?

This vitamin is essential for a healthy body, as it helps develop red blood cells,

This vitamin is essential for a healthy body, as it helps develop red blood cells,