Debates are hitting headlines as Robert F. Kennedy Jr. voices new concerns about fluoride in public water systems. But what does the science actually say? And how should we as consumers evaluate the risks and benefits?

If your water supply is sourced from a municipal reservoir, you’re consuming more than just water with every glass you drink from your tap — you’re also getting a carefully regulated dose of fluoride in addition, depending on the water source, calcium, magnesium, sodium, and potassium It is fluoride that has quietly helped prevent millions of cavities over the past 80 years.

But some now claim that fluoride may be harming children’s brains. So, what exactly are we drinking — and is it safe?

What Is Fluoride and How Does It Get into Our Water?

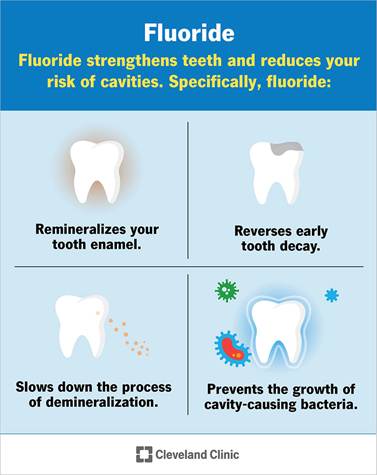

Fluoride is the naturally occurring anion of the element fluorine, found in rock, soil, plants, and ultimately in your water sources. It is known for reversing demineralization, strengthening tooth enamel, and repairing tooth decay.

Therefore, for tooth care, particularly for children, across the population, water systems carefully add fluoride to reach a safe and effective concentration of 0.7 mg/L — the level recommended by both the CDC and U.S. Public Health Service.

Municipal systems use one of three fluoride compounds:

- Fluorosilicic acid (most common)

- Sodium fluorosilicate

- Sodium fluoride

As one water-treatment engineer explains: “We monitor fluoride levels constantly to hit that sweet spot—enough to protect teeth, but far below levels that could discolor or harm them.”

Consider this:

Fluoridating a standard barrel of drinking water requires just a few drops of fluoride — enough to protect your teeth with every sip. For those homes on well water, pediatricians often give fluoride as a small daily tablet to protect teeth.

The Proven Benefits of Water Fluoridation

Since Grand Rapids, Michigan became the first U.S. city to fluoridate its water in 1945, fluoride has led to a dramatic 25%–35% reduction in cavities across children and adults. The CDC calls community water fluoridation one of the top 10 public health achievements of the 20th century.

The economic impact is equally significant: for every dollar spent on fluoridation, communities save about $20 in avoided dental treatment costs — preventing painful procedures, school absences, and financial burdens, particularly for lower-income families.

RFK Jr.’s Challenge: The Risks, Studies, and the Stakes

Robert F. Kennedy Jr., now leading the Department of Health and Human Services, has emerged as one of fluoride’s most vocal critics, calling it “industrial waste” and suggesting links to lowered IQ, thyroid dysfunction, bone cancer, and neurological harm.

At the center of his argument are two studies:

The National Toxicology Program (NTP) 2024 Review: This cautiously reported that fluoride levels at or above 1.5 mg/L may be associated with slight IQ declines in children.

Additionally, a 2025 Meta-Analysis by Philippe Grandjean (Annual Review of Public Health) suggested potential neurodevelopmental risks from fluoride exposure during pregnancy — again, at exposure levels higher than U.S. public drinking water standards.

What the Science Says: Context and Dosage Matter

Here’s the catch: the levels referenced in these studies far exceed the fluoride levels used in U.S. water systems.

- Standard U.S. fluoridation level: 0.7 mg/L

- Levels where potential risks appear (in studies): 1.5–2.0 mg/L

- Average adult daily water consumption: ~2.5 liters/day

- Fluoride intake at U.S. standards: ~1.75 mg/day

To approach the fluoride intake levels associated with possible neurotoxicity, an adult would need to consume over 11 liters or about 3 gallons of fluoridated water per day, every day, for years.

For comparison, an adult African elephant drinks 50 to 100 liters of water daily. To reach concerning fluoride levels, you’d need to drink more like an elephant than a typical person at your kitchen sink, without a filter, daily, for years. You’re more likely suffer from fluoride-induced nephrotoxicity before finishing up those 21 gallons a week.

Even at these higher exposure levels, these studies RFK references only observe correlations — not causation — and often rely on data from countries where fluoride levels in untreated, unregulated, groundwater naturally reach 5–10 mg/L, which is many times higher than U.S. water systems allow.

As the American Academy of Pediatrics summarizes, fluoridation is safe. Studies that suggest harm use higher doses than what’s found in U.S. water supplies, and the risks are far outweighed by the benefits for children’s oral health.

Headlines vs. The Truth: What Experts Say

What the Headlines Say:

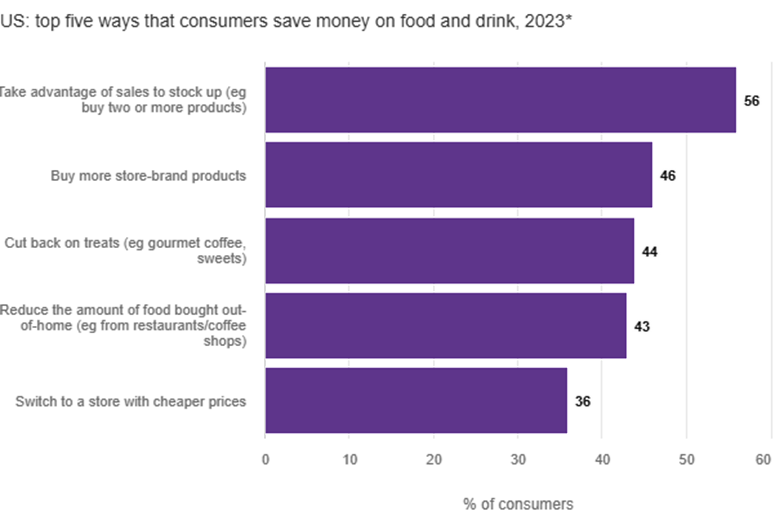

“As Fluoride Bans Spread, Who Will Be Hit the Hardest?” — Time.com: A national fluoridation halt could add 25 million cavities and $9.8 billion in extra dental costs, especially affecting children and low-income families.

“As Fluoride Bans Spread, Who Will Be Hit the Hardest?” — Time.com: A national fluoridation halt could add 25 million cavities and $9.8 billion in extra dental costs, especially affecting children and low-income families.- “Study Shows Rise in Children’s Cavities If U.S. Removed Fluoride from Water” — The Guardian: Modeling data estimated 25.4 million extra cavities among American children over five years if fluoridation were discontinued.

- “Fluoride Toxicity Alerts” is another site that is not based in science. Be sure to check who is funding sites like these and the data that they are basing their claims on.

What the Experts Say:

- Dr. Steven Levy, University of Iowa: “Having a very low level of fluoride in the water was substantially protecting against cavities.”

- FactCheck.org: “The mineral fluoride, at the right dose, has been shown to reduce the risk of tooth decay… The CDC and multiple expert groups endorse water fluoridation as a safe way to reduce tooth decay.”

- Dr. Vivek H. Murthy, U.S. Surgeon General: “Fluoridation is the single most effective public health measure to prevent dental decay and improve oral health for everyone, regardless of income or access to dental care.”

- Dr. Myron Allukian, American Public Health Association: “Fluoride at the level used in community water systems has repeatedly been shown to be safe and effective.”

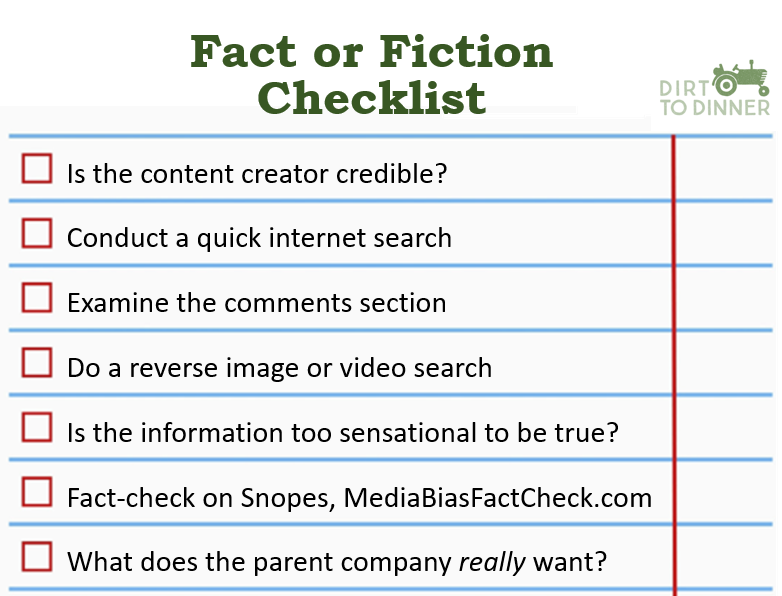

The Importance of Verification: A Reminder for All of Us

Fluoridation works. At properly regulated levels, it is safe, effective, and supported by over 80 years of real-world evidence. While RFK Jr.’s concerns raise legitimate questions for ongoing study, they focus on fluoride exposures far above what U.S. communities use.

We all deserve clean, safe water — but skepticism alone is not enough.

As consumers, parents, and voters, we must:

- Verify claims by reading studies directly, not just headlines

- Understand the dose: what levels are truly harmful versus helpful

- Look at real-world data: 80 years without unexplained neurotoxic effects

- Trust but confirm: science evolves, but so do misleading narratives

Beyond Fluoride: Why Food and Science Literacy Matter

At Dirt to Dinner, we believe deeply in understanding not only what we eat and drink, but also how public science is communicated. Fluoride is one of many public health debates clouded by partial information. So are:

- GMOs — proven safe across 300+ studies, yet still widely misunderstood

- Pesticide Residues — often far below safety thresholds but poorly explained

- Hormones in Meat and Dairy — regulated and minimal, but still widely feared

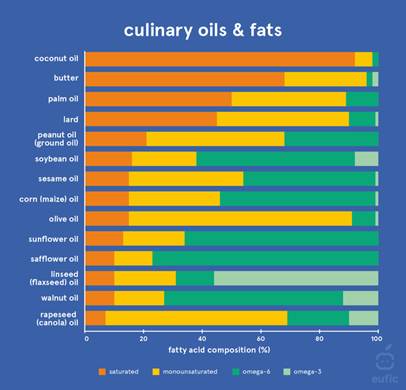

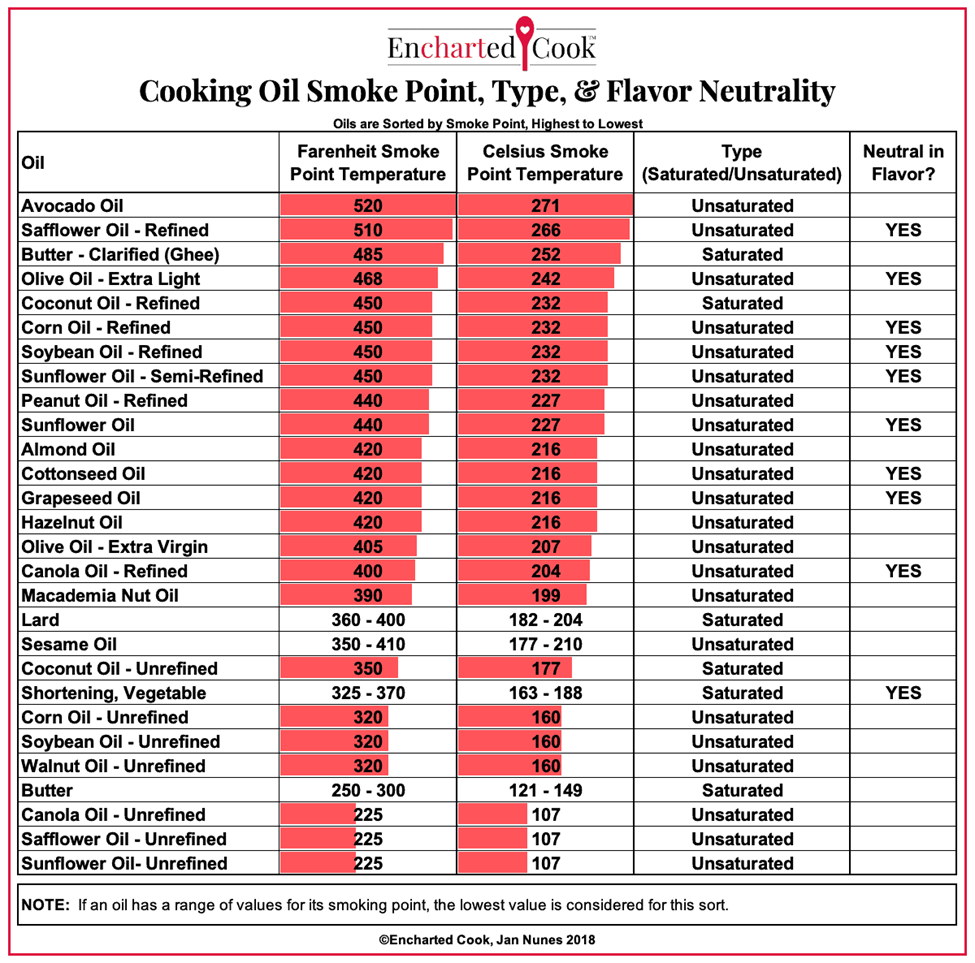

- Seed Oils — debated endlessly online but rarely with full scientific nuance

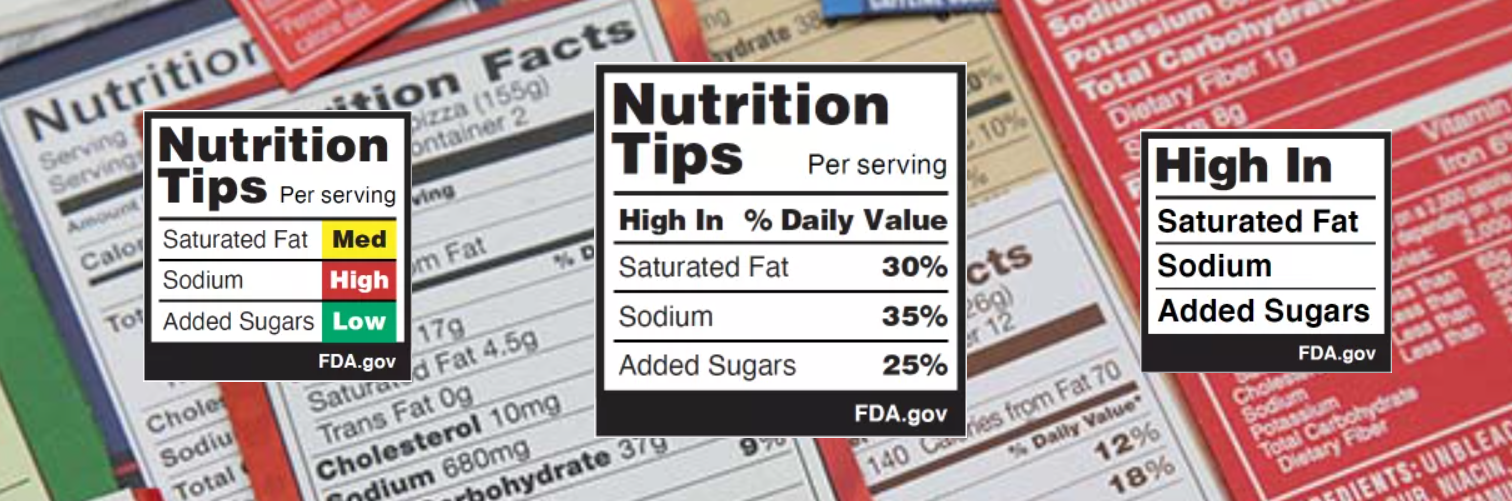

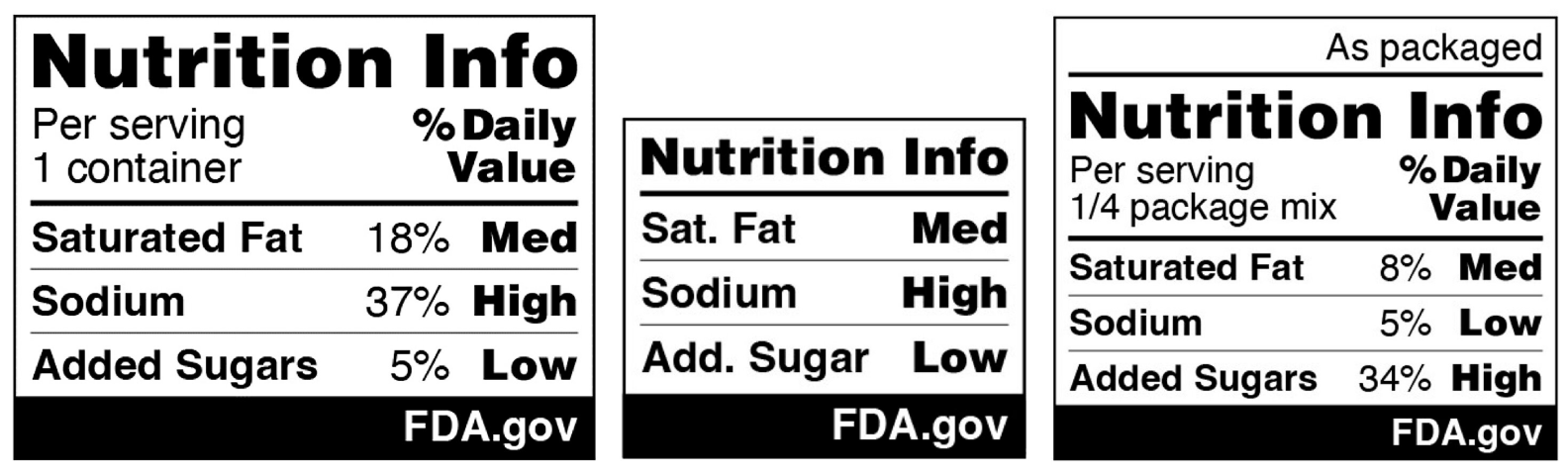

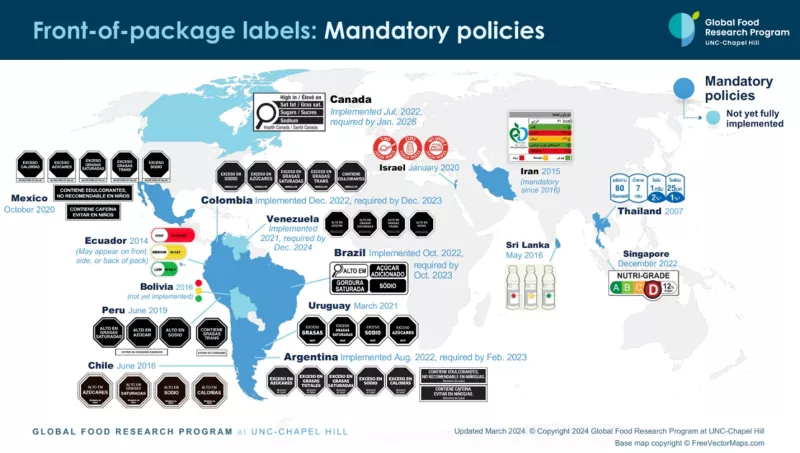

- Food Labeling — buzzwords like “natural” or “non-GMO” often cause confusion

Advocates claim it reduces inflammation, improves mental clarity, and helps manage glucose levels, and promotes weight loss. However, the reported benefits of this diet are more anecdotal than clinical. In fact, multiple studies cite the dangers of this diet, including

Advocates claim it reduces inflammation, improves mental clarity, and helps manage glucose levels, and promotes weight loss. However, the reported benefits of this diet are more anecdotal than clinical. In fact, multiple studies cite the dangers of this diet, including

For instance, high consumption of saturated fats like beef tallow – which

For instance, high consumption of saturated fats like beef tallow – which  Yes, ACV can slightly

Yes, ACV can slightly  Experts generally agree that most people, especially women and older adults,

Experts generally agree that most people, especially women and older adults,

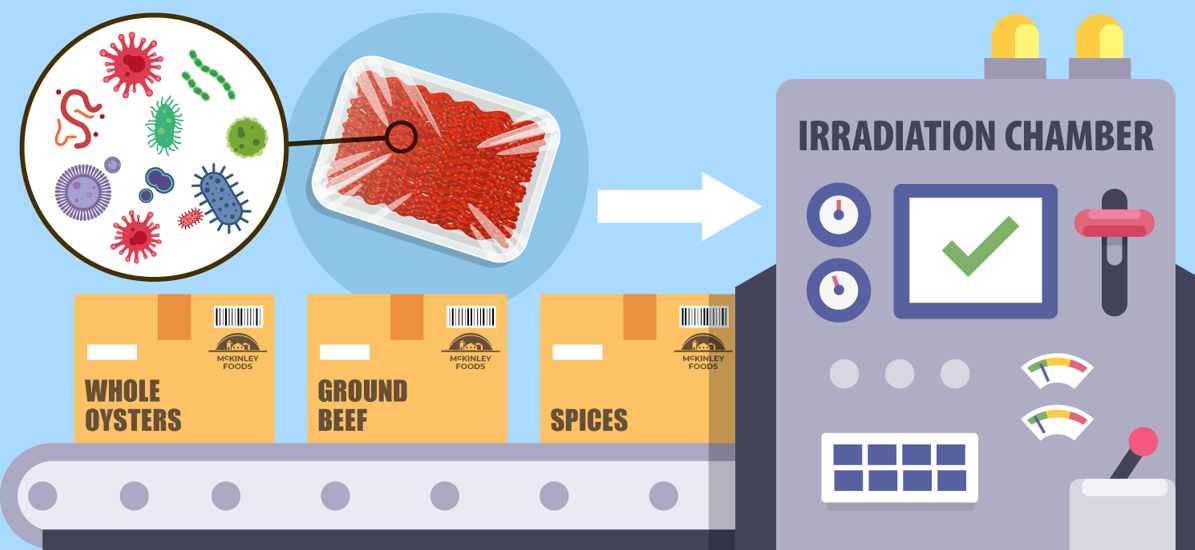

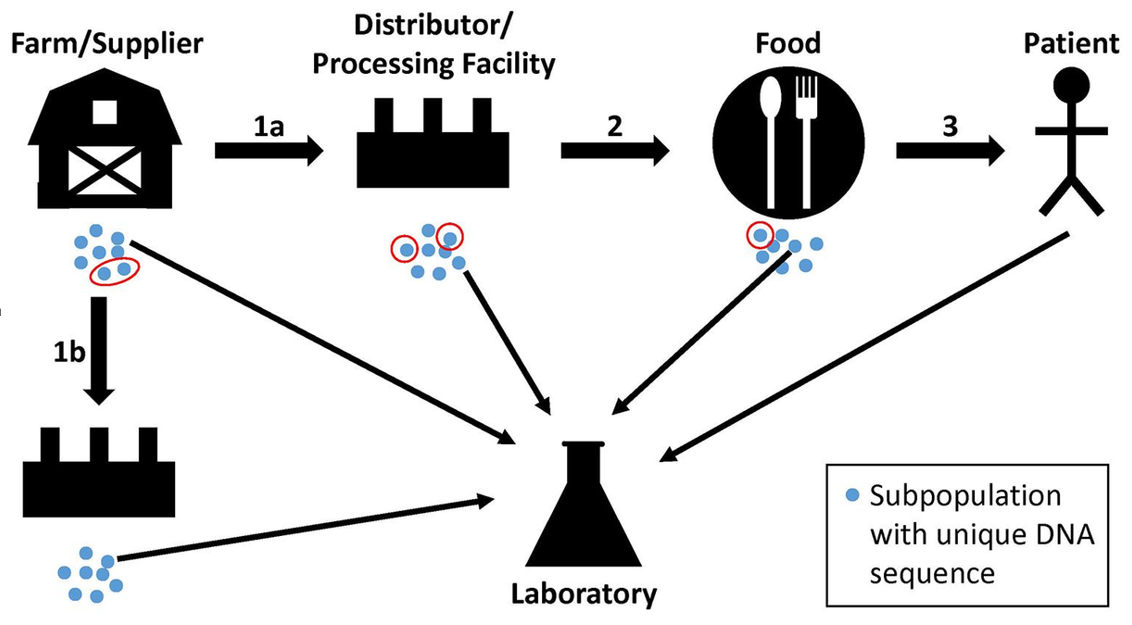

During the 2022 E. coli outbreak in leafy greens,

During the 2022 E. coli outbreak in leafy greens,

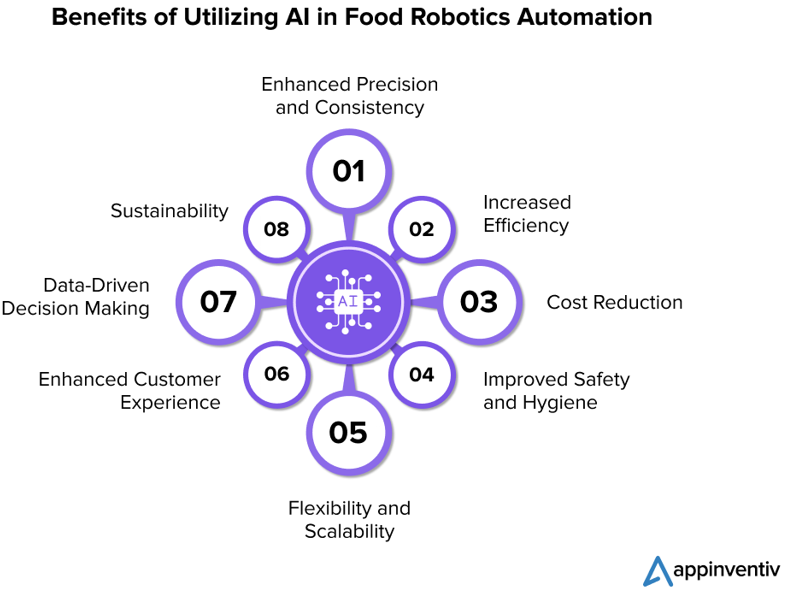

This allows agencies to prioritize inspections based on actual risk, not just routine schedules.

This allows agencies to prioritize inspections based on actual risk, not just routine schedules.

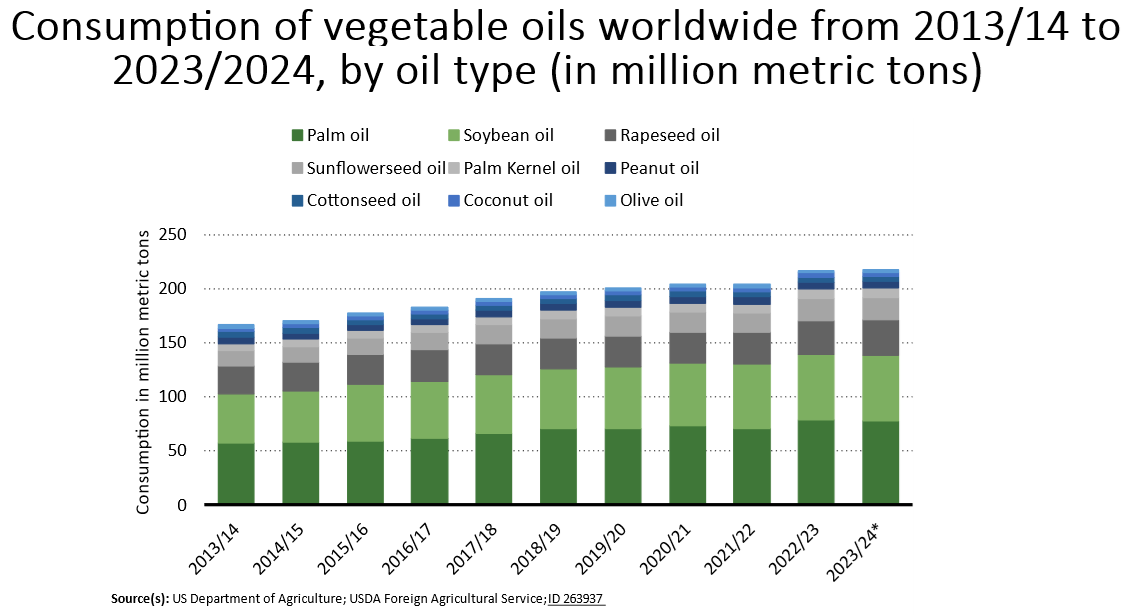

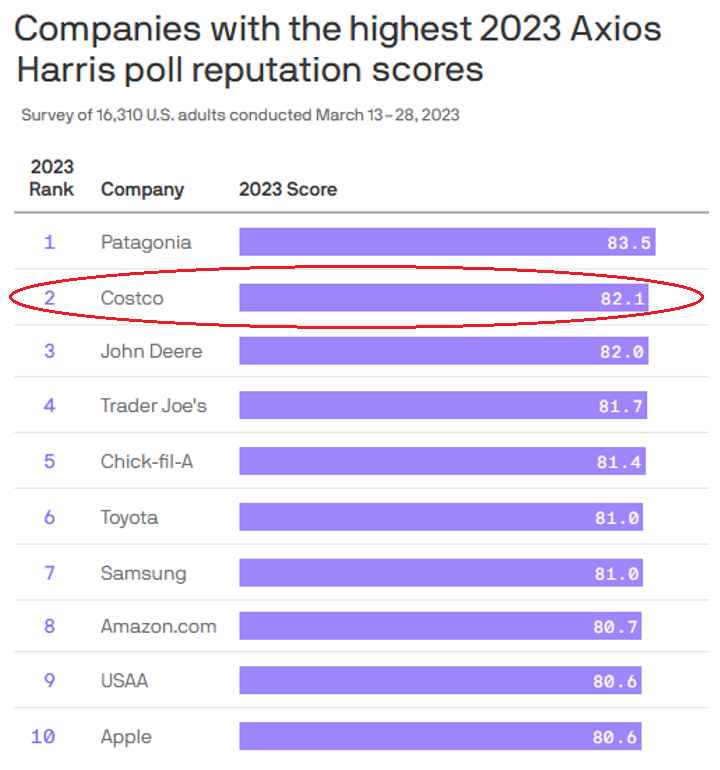

This isn’t just about cooking with oil. It’s part of a broader philosophical divide. As institutional trust declines, many are turning to tradition and nature for guidance—assuming, sometimes wrongly, that these values offer more than modern science.

This isn’t just about cooking with oil. It’s part of a broader philosophical divide. As institutional trust declines, many are turning to tradition and nature for guidance—assuming, sometimes wrongly, that these values offer more than modern science.

RFK is right: so many Americans are unhealthy.

RFK is right: so many Americans are unhealthy.

The Thin Mint headlines may be new, but glyphosate conversations are years old.

The Thin Mint headlines may be new, but glyphosate conversations are years old. Both the

Both the  It’s also important to rinse all

It’s also important to rinse all

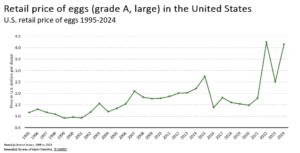

A local supermarket worker described the retail situation in simple terms: “Eggs come in on Friday’s truck. By Monday, they are pretty much gone.”

A local supermarket worker described the retail situation in simple terms: “Eggs come in on Friday’s truck. By Monday, they are pretty much gone.”

The FDA’s decision to act on Red Dye No. 3 after decades of inaction may signal a shift towards more proactive regulation of food additives.

The FDA’s decision to act on Red Dye No. 3 after decades of inaction may signal a shift towards more proactive regulation of food additives. There are many substitutes for Red Dye No. 3, such as beet juice, purple sweet potato extract, red cabbage extract, carmine, and pomegranate juice. These natural substitutes align with growing consumer preferences for clean-label ingredients. After all, many of us would rather consume pomegranate juice in Jell-o than red dye.

There are many substitutes for Red Dye No. 3, such as beet juice, purple sweet potato extract, red cabbage extract, carmine, and pomegranate juice. These natural substitutes align with growing consumer preferences for clean-label ingredients. After all, many of us would rather consume pomegranate juice in Jell-o than red dye.

As for the salad…

As for the salad…