To all my Dirt-to-Dinner friends,

Thanks to everyone for the many, many expressions of concern and support following the devastating effects of Hurricane Helene.

My part of North Carolina was hit especially hard, with epic flooding and devastation that simply wiped away many of the small towns here and left cities like Asheville reeling from destruction almost beyond description. The photo on the right shows Helene’s impact on my hometown.

My part of North Carolina was hit especially hard, with epic flooding and devastation that simply wiped away many of the small towns here and left cities like Asheville reeling from destruction almost beyond description. The photo on the right shows Helene’s impact on my hometown.

Remember just how widespread and damaging this storm has been for us.

Helene brought a 500-mile path of death and destruction from Florida to the southern Appalachian Mountains. Our state Department of Health and Human Services placed the death toll from Helene at 95 across 21 of our 100 counties – with another 200 still missing.

Almost three million people lost power across the affected states, including me, for eight days. A gaunt work crew from far-off Ohio sent to restore our power politely declined our offer of some camp-stove instant coffee. Too many people still need our help for us to spend time drinking coffee, one of them said without a hint of pretension.

As if farming wasn’t bad enough this year…

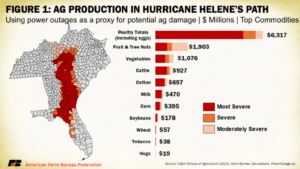

Like most southern states, Georgia has a robust and diversified agricultural production system. But Helene brought four months’ worth of rain in barely two days to some areas of the state. Winds estimated at 79-111 miles per hour helped devaste a huge swatch of the Peach State’s prime production areas.

Georgia Agriculture Commissioner Tyler Harper commented on the hurricane’s effect on Georgia’s farms and farm families:

“Every commodity in our agriculture industry has been impacted by this storm. You got poultry houses that are leveled, pecan trees that are down.

“That means we’ve lost that crop, not only for this year but we’ve lost that crop for years to come.”

Preliminary estimates by the state’s Agriculture Department, the Forestry Commission and University of Georgia placed the total economic damage to the state’s agriculture at $6.5 billion. Harper estimated that about 30 percent of the overall economic output from Georgia’s farming industry was lost and with nothing to sell, the families and workers that make the state’s agriculture what it is are in need of help.

Atlanta television station WBS reported that the American Farm Bureau estimated Georgia had suffered a 75 percent loss in the pecan crop, and 80 percent in the poultry industry. Other reports said as many as 100 poultry houses no longer exist. That’s a huge hit for a sector that accounts for about one-third of the state’s agricultural economy.

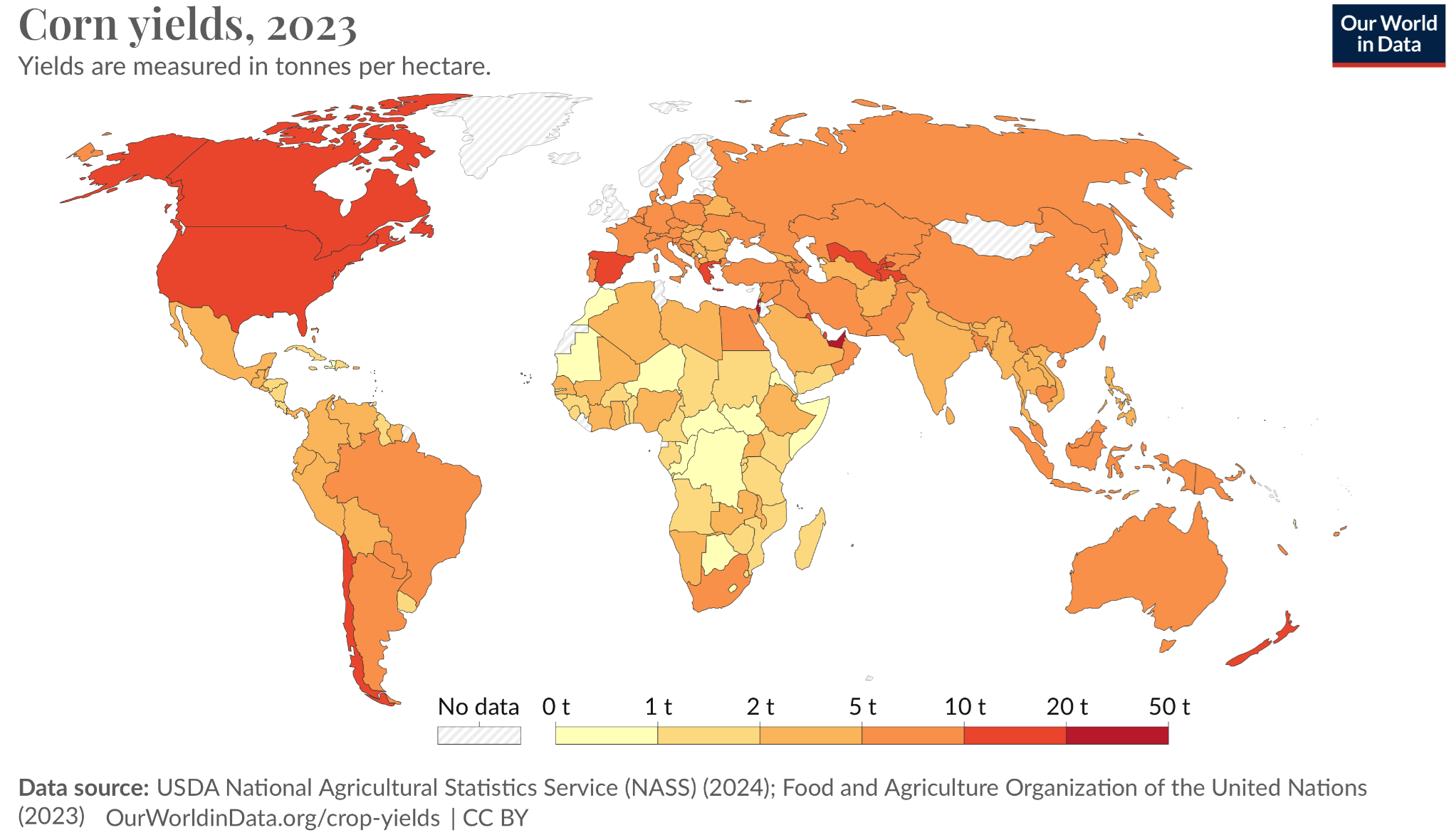

Corn is the most widely grown crop in the state, notably in the southern half of the state. Autumn crops of produce also are critical, with one farmer estimating his losses alone at $7 million – with most of those crops not covered by crop insurance. Peach farmers also report extensive damage to their trees.

The storm brought notable immediate and lasting damage to at least two of the state’s most important crops: cotton and pecans. Cotton helps clothe us. Pecans are a mainstay of confections and notably holiday cooking. Cotton accounts for $1 billion of the state’s farm economy, pecans another $400 million. Both crops provide examples of the potential consequences of extreme weather events to producers almost anywhere.

Helene devasted as much as a quarter of the state’s entire pecan acreage. Pecan trees can take as long as 25 years to reach full maturity – meaning it will take years for the lost trees to be replaced.

According to Lenny Wells, the University of Georgia’s extension pecan specialist:

“”What we are hearing from most growers is that large trees (40-50 years and up) have suffered about a 70 percent loss and younger trees have suffered somewhere around a 40 percent loss. When I say loss, I am referring to trees blown completely down.

“These numbers are yet to be confirmed but from what I have seen myself and gauging by what we saw from Hurricane Michael a few years ago, I don’t believe these numbers are an exaggeration. I have heard from people in the damage area who have five or six trees left standing, and several who have no trees left standing.”

Cam Hand, the school’s extension cotton specialist, painted an equally somber picture:

“It seems like across the state, we lost somewhere between 35 percent to 40 percent of our (cotton) crop. … And there are fields worse than that and some that aren’t that bad, but that’s what the number looks like. And we’ve still got a long way to go on getting data and seeing the reductions in fiber quality associated with this storm.”

Let’s not forget another of the state’s key crops, supporting an industry worth an estimated $2 billion: peanuts. Georgia plants about 770,000 acres of the 1.8 million acres of peanuts grown in the United States and accounts for 53 percent of total consumption, according to industry figures. Officials are still calculating the extent of Helene’s damage to Georgia’s peanut crop. They also somberly note that Helene’s path cut through not just the state’s peanut-growing areas but the heart of the prime peanut-growing acres across the southeast.

And here in North Carolina, corn is one of our most important crops. The latest government reports show that we’ve completed 72 percent of our corn harvest, compared with 84 percent complete at this point in the last harvest season. But weather has taken its toll throughout the year, from dry conditions in the summer to torrential rains this autumn.

Only 12 percent of North Carolina’s corn crop is rated as “good,” another 11 percent “fair” – and a whopping 77 percent either “poor” or “very poor.”

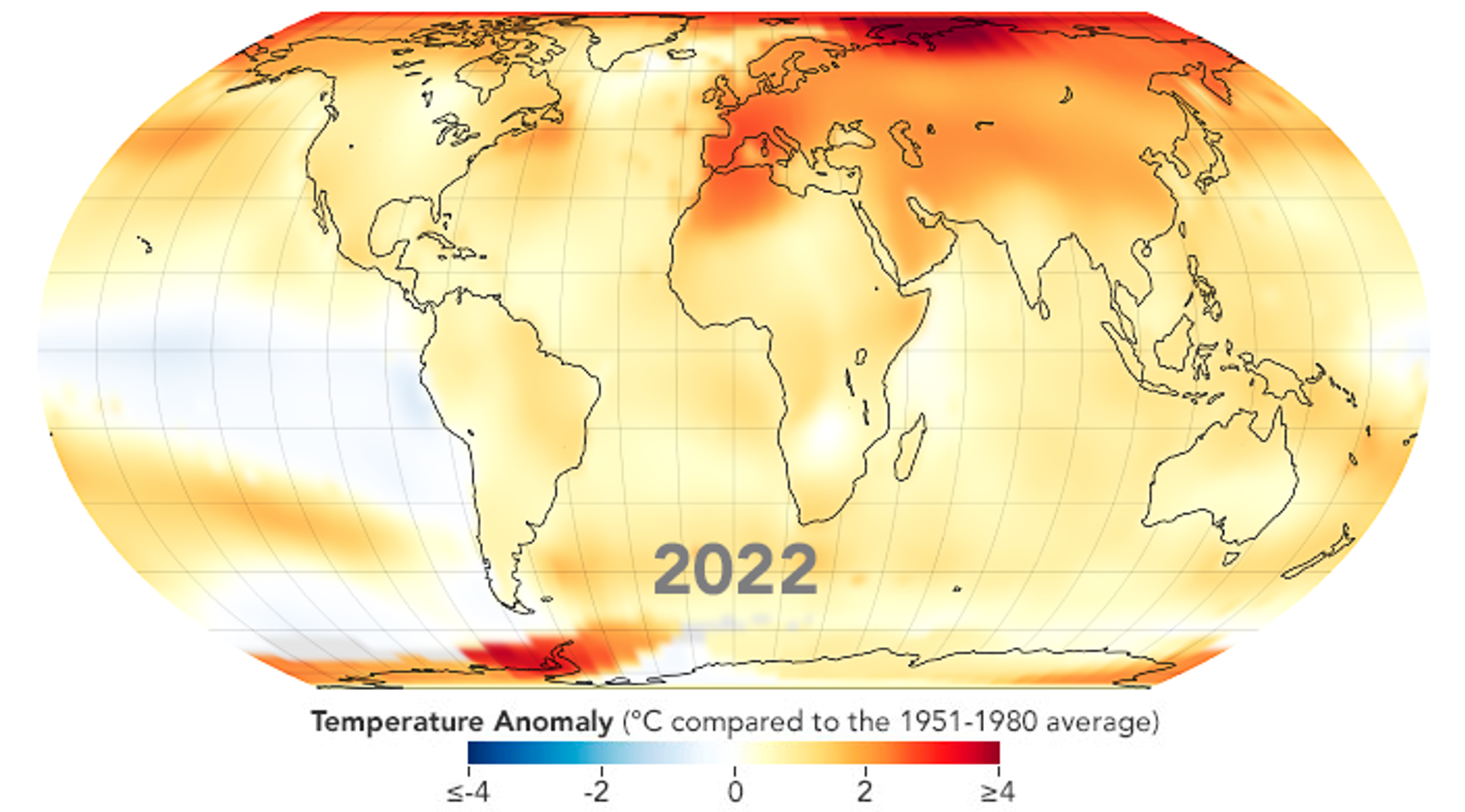

I can’t think of a better barometer of the critical role of weather in our food system – here or anywhere else.

I’m pleased to report that we are recovering

In fact, perhaps the biggest ray of sunshine in all of this – if there is one – is the remarkable way people have pulled together to deal with the situation. No one has simply given up, and I’ve encountered precious few individuals prepared simply to wait for help from some government agency or an anonymous distant benefactor.

Neighbors are banding together to clear debris, and the sound of chain saws throughout the day from all directions tells me we’re out there thinking about the future, far more than about the past.

Thanks, everyone, but we are well on our way for getting through this.

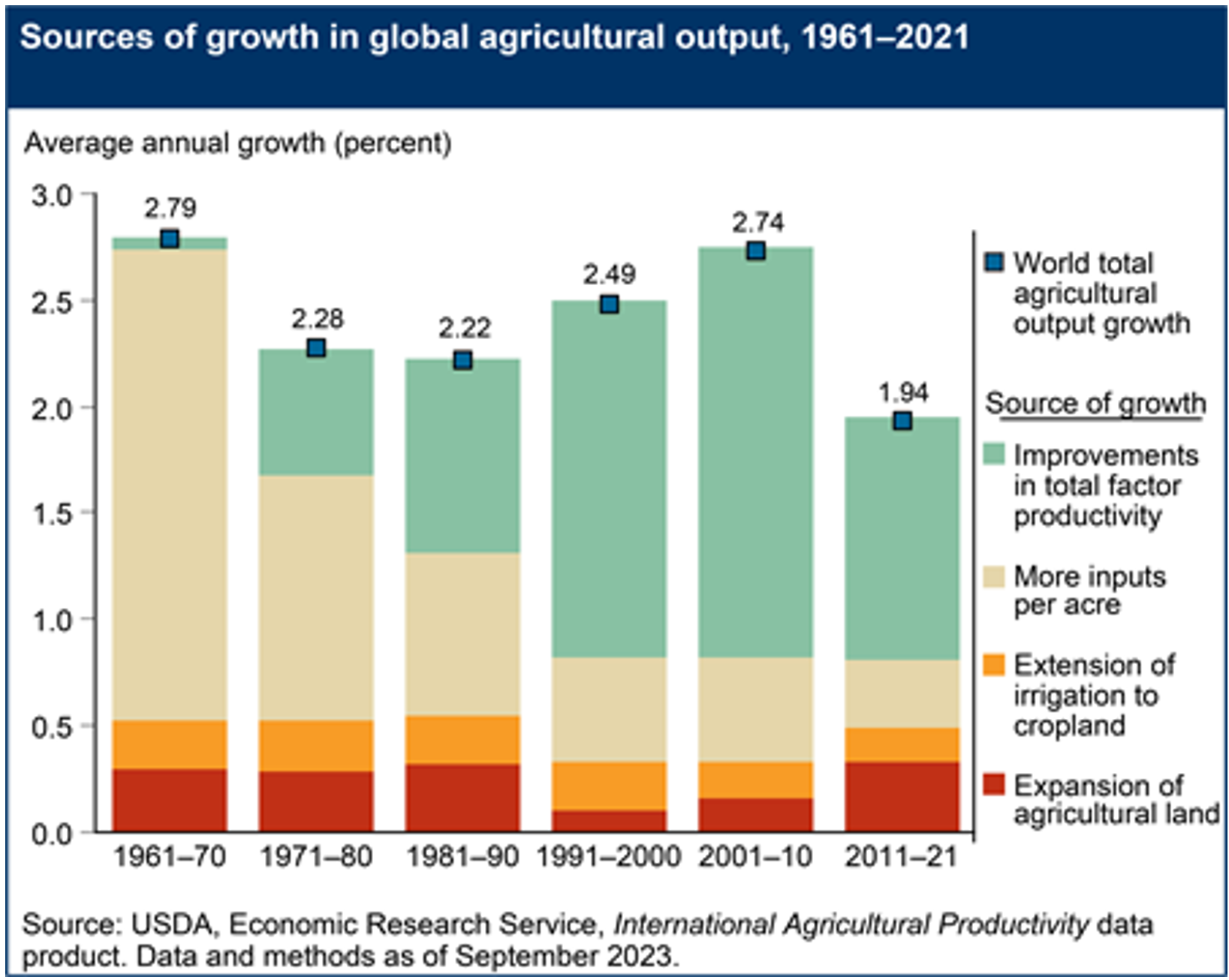

As I watched all this unfold around me over almost an entire month, I’ve also noticed that the agricultural community is doing its part in the relief effort. I suppose farmers are more used to dealing with the vicissitudes of weather than we complacent consumers. Excessive rain, extreme heat, drought and the pests that come with them are part and parcel of the farming way of life. Finding ways to cope with them is the flip side of the farming coin.

The good news about agriculture, if there is any, is in the spectacular efforts of farmers to get ahead of the storm.

Thanks to the accurate heads-up provided by weather experts in the days before Helene came ashore, many farmers were able to get into the fields to speed the normal pace of the traditional farm harvest season that is underway at this time of the year. Key southern crops have been hit – some hard – but by and large an alert farming community helped cut the extent of devastation in real and meaningful ways.

But there’s still much to do

Even so, Helene’s effects on agriculture in the Southeastern United States are almost beyond comprehension.

Broken buildings, mud and silt are everywhere, still.

Roads are still closed. Downed trees, snapped power poles and drooping electrical cables line what roads are open. Obviously, some level of disruption to normal flow of crops and animals to market of course can be expected, creating spot shortages and sometimes lack of available supplies.

A visit two days ago to a prominent Asheville supermarket showed the effects in real time.

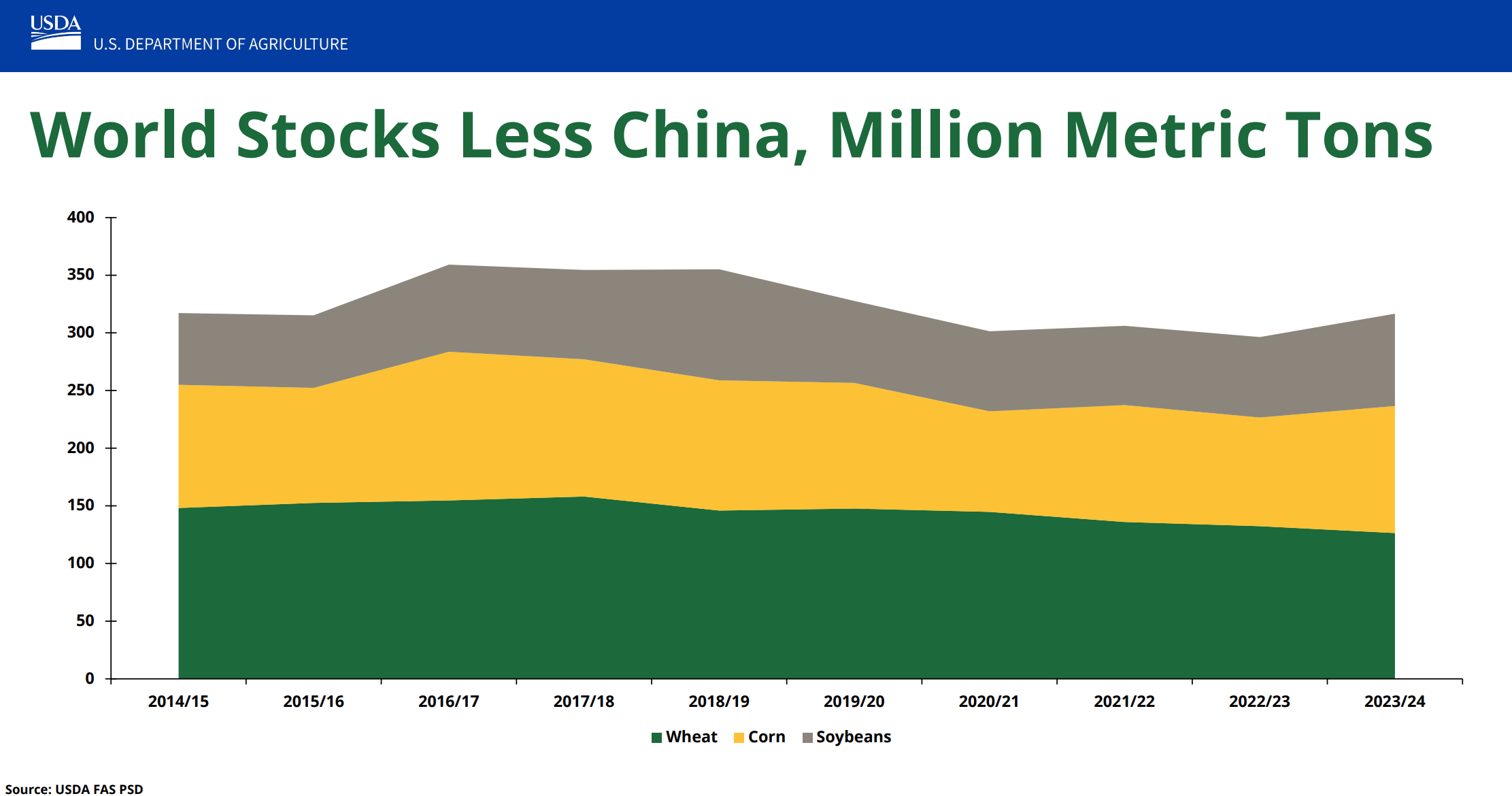

Weeks after the storm, the items on the previously robust aisles are sparse and picked over, and huge swatches of store shelves remain empty. Eggs and dairy products are in limited supply, and good luck finding any 2% milk.

Frozen food cases are bare, after extended periods without the power that makes them possible.

“Bear with us,” the harried store manager told me. “We’ll be back. Count on it.”

That’s the voice of resilience and optimism.

The logistics system that delivers supplies and takes crops and animals to market has been severely disrupted in many areas, where roadways and bridges no longer exist. The famous Blue Ridge Parkway and other scenic attractions in this part of our state are completely shut down and will be for some time.

Local roadways are just gone in many places. The vital east-west Interstate 40 corridor remains closed in long stretches from Asheville to the Tennessee border, with eastbound lanes swept away by rains and mudslides. For those who don’t know our local geography, that’s roughly 50 miles.

It’s still possible to see farm equipment bogged down in fields that weren’t simply muddy. They were quagmires if lucky, and submerged if not. Thank the heavens above for the past week of sunny, dry conditions.

Advance weather notices helped many farmers avoid calamity. But the sheer speed of the rising waters and the extraordinary levels of water on historically safe fields and city streets took all of us by surprise, nonetheless. This was a near Biblical event for people in this area, none more so than our local farming community.

The floods, tragically, have left hundreds of my fellow state residents dead or missing.

Finding a new path amidst the devastation

On top of that, uncounted animals also are dead or missing. Some of the luckier animals were stranded around this area, and supplies of hay and feed completely lost or rendered inaccessible. I’m told by my local farming friends that dairy farmers have faced enormous challenges dealing with their herds, without reliable delivery of feed, supplies and the ability to move product…or the power they need for milking and other management duties. Truckloads of hay from Pennsylvania and other somewhat drier distant areas have helped fill the gap for animal feed.

The peculiar thump of helicopters in the skies above delivering food, water and emergency supplies for desperate people and animals has become a normal sound of the day – and music to our ears.

Pastureland was flooded and remains wet, weeks after the storm. Some poultry houses no longer exist. Many barns, out-buildings and other elements of the farming infrastructure are left damaged, in rubble, or simply vanished down the turbulent river flows. I sense that we’re transitioning from a period of emergency response to a slower, more deliberate process of rebuilding and recovery. It will take months, perhaps years, to repair and recreate all the resources needed to move food from dirt to dinner. But we’re going to do it.

This may be the best example of “regenerative agriculture” that I’ve found so far.

As I’ve watched all this unfold around me, I also tried to take a look at how other areas hit by Helene have fared. The picture is much the same, across large portions of Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina and Tennessee, not to mention the Florida Panhandle and parts of Kentucky, Virginia and West Virginia. (Florida has its own story to tell about hurricanes, which probably deserves special attention.) But as a loyal Carolinian with a well-documented southern bias, I’m sensitive to what all this means for southeastern farming and ranching, and the key crops that form the foundation of our farm economy.

How we can help

And maybe more of concern to the average consumer, the effects of Helene on the poultry industry are significant. For example, the National Chicken Council (yes, there is a national chicken council) notes that Georgia, North Carolina, Arkansas, Alabama, and Texas were the top five states for liveweight broiler production in 2023, accounting for 55.5 percent of total U.S. federally inspected production. Replacing the productive capacity for broilers, layers, eggs, turkeys and other poultry lost because of Helene won’t happen overnight.

If anyone wants to offer help to the people ravaged by Hurricane Helene, please visit CharityNavigator’s Hurricane Helene Support page for an overview of various charitable organizations helping in the relief effort.

Thanks again for all your support and concern. We all appreciate it more than we hope you will ever know.

– Garland

Interested in learning more?

Interested in learning more?

My part of North Carolina was hit especially hard, with epic flooding and devastation that simply wiped away many of the small towns here and left cities like Asheville reeling from destruction almost beyond description. The photo on the right shows Helene’s impact on my hometown.

My part of North Carolina was hit especially hard, with epic flooding and devastation that simply wiped away many of the small towns here and left cities like Asheville reeling from destruction almost beyond description. The photo on the right shows Helene’s impact on my hometown.

We’re still without our long-overdue

We’re still without our long-overdue

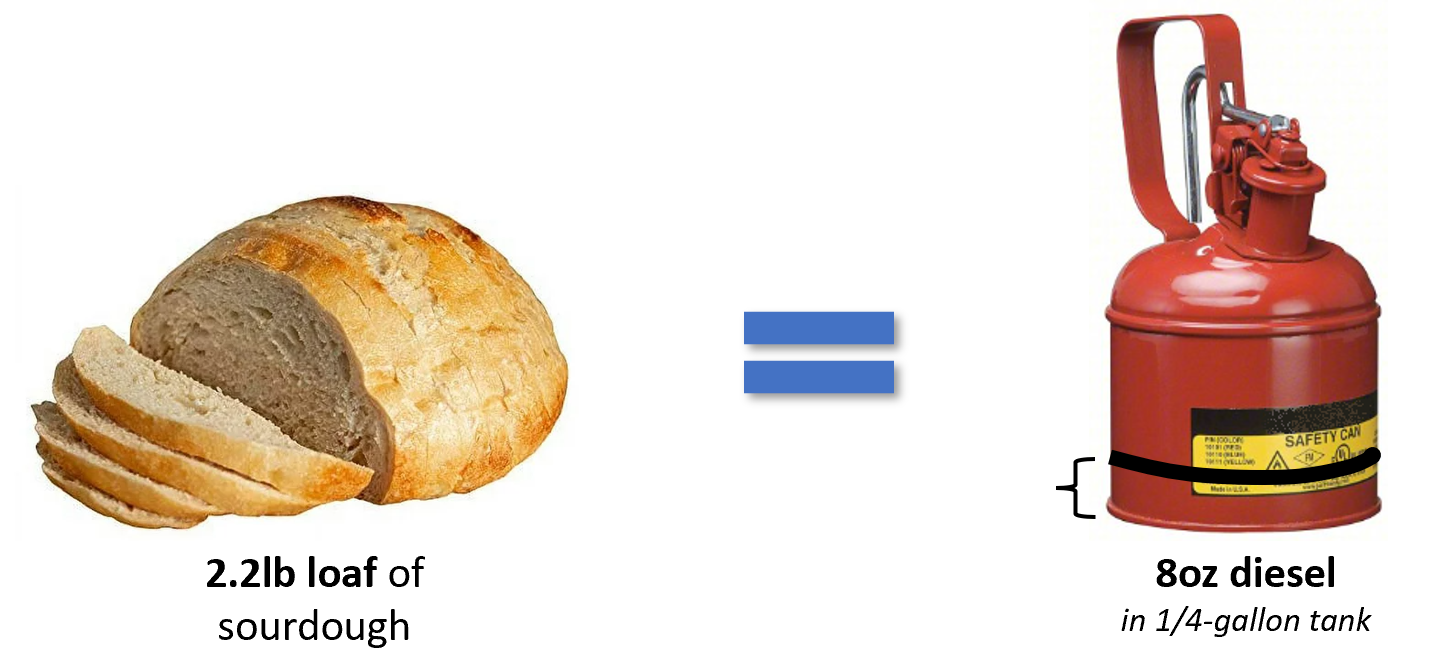

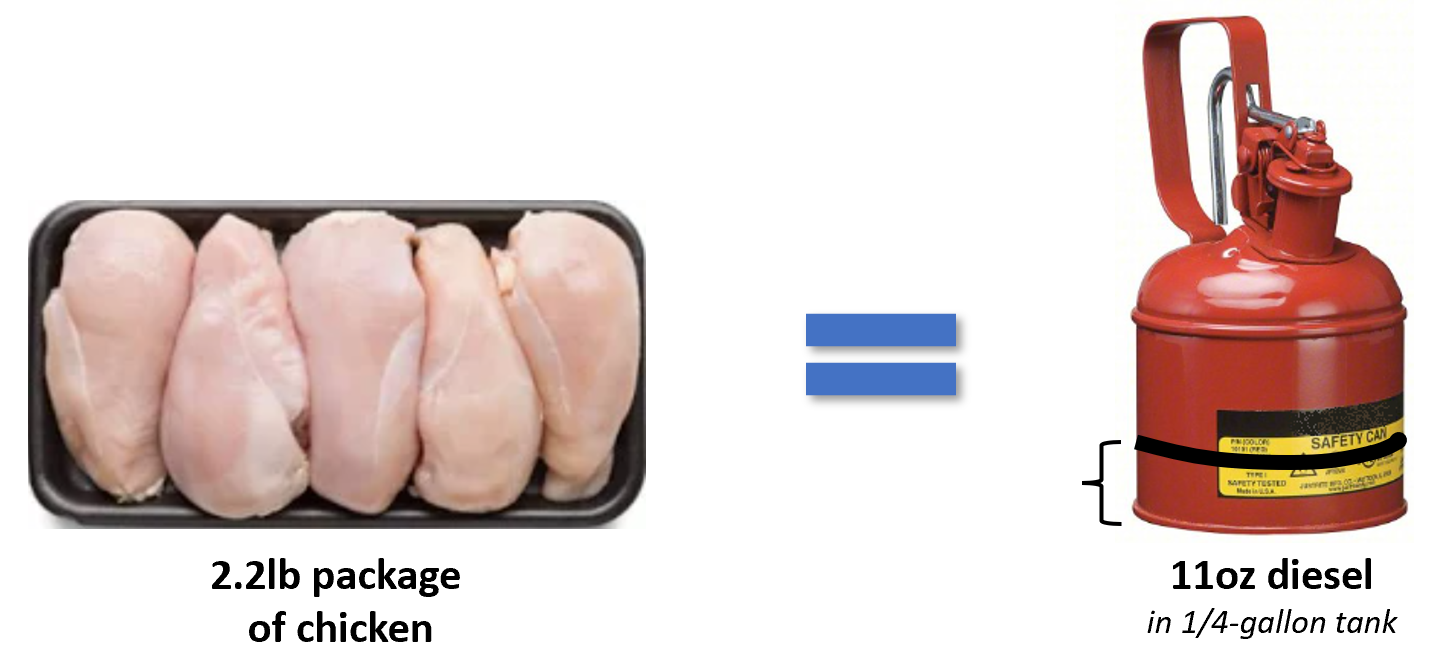

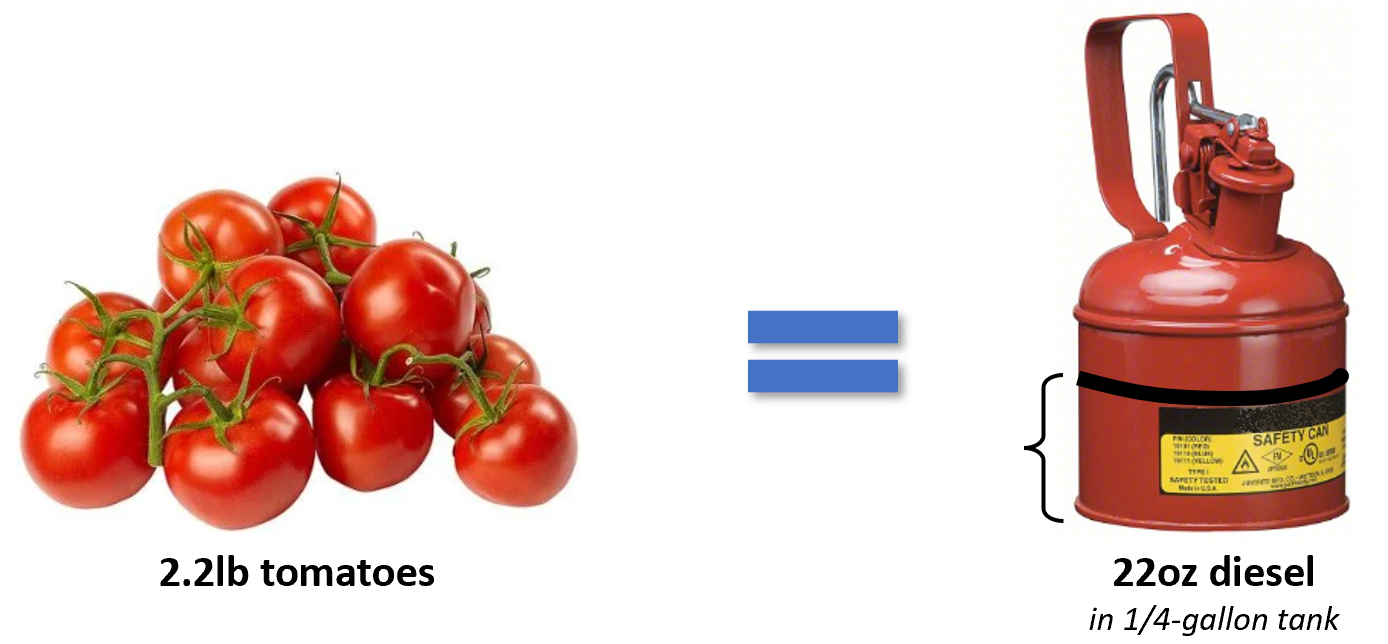

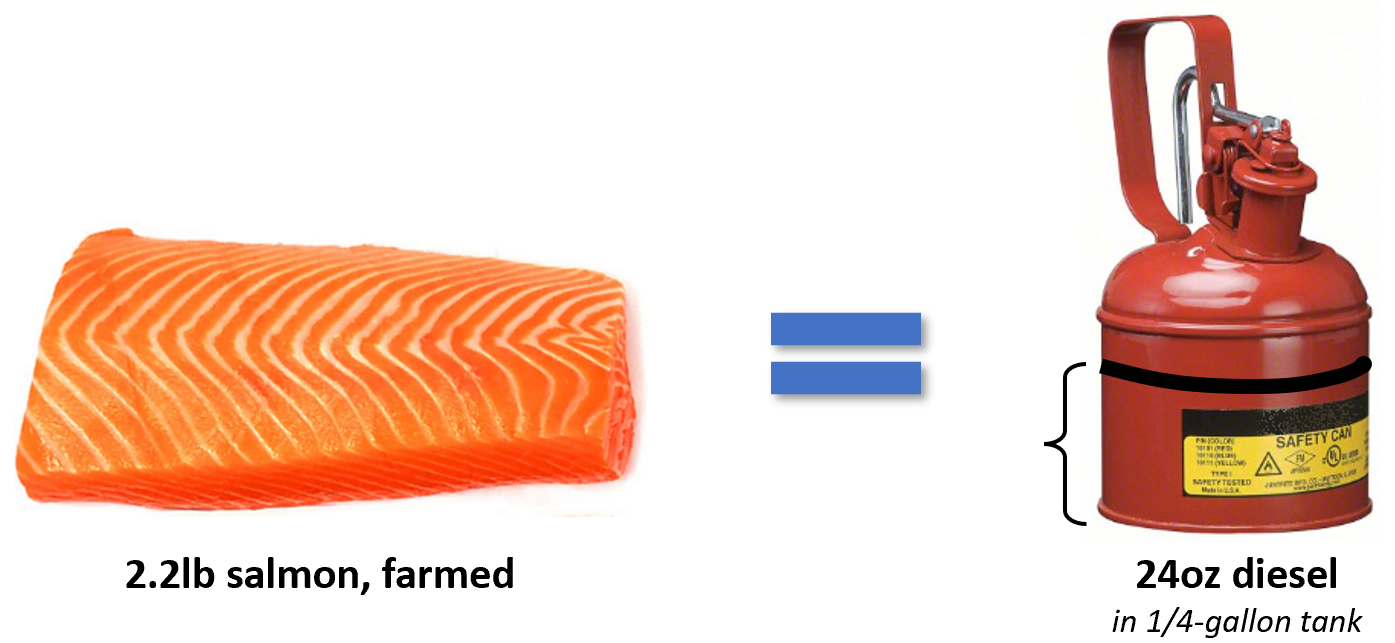

Moving to vehicles not dependent on fossil fuels is a noble objective. But once again, the reality is that such a transformation in a system as large as the U.S. food system will be an expensive proposition. The more rapid the required conversion, the higher the risk of short-term adverse effects on the producer bottom-line.

Moving to vehicles not dependent on fossil fuels is a noble objective. But once again, the reality is that such a transformation in a system as large as the U.S. food system will be an expensive proposition. The more rapid the required conversion, the higher the risk of short-term adverse effects on the producer bottom-line.

Wildfire smoke is a devil’s brew of harmful ingredients – carbon monoxide, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, water vapor and various particulate matters. As fires burn, these substances rise in the air, driven upward by heat, finding prevailing winds aloft capable of carrying them thousands of miles.

Wildfire smoke is a devil’s brew of harmful ingredients – carbon monoxide, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, water vapor and various particulate matters. As fires burn, these substances rise in the air, driven upward by heat, finding prevailing winds aloft capable of carrying them thousands of miles. The scientific community continues to explore the question of the relationship between exposure and lasting health damage.

The scientific community continues to explore the question of the relationship between exposure and lasting health damage.

Food waste occurs due to many reasons—spoilage, issues during drying, milling, or transporting, processing that exposes food to damage and equipment malfunction.

Food waste occurs due to many reasons—spoilage, issues during drying, milling, or transporting, processing that exposes food to damage and equipment malfunction. A consumer report from Mintel detailed that the acceptance of

A consumer report from Mintel detailed that the acceptance of

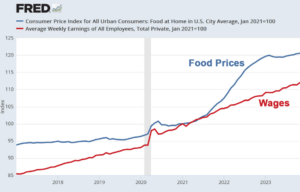

The latest data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) pegs the annual inflation rate for food running at 6.8%.

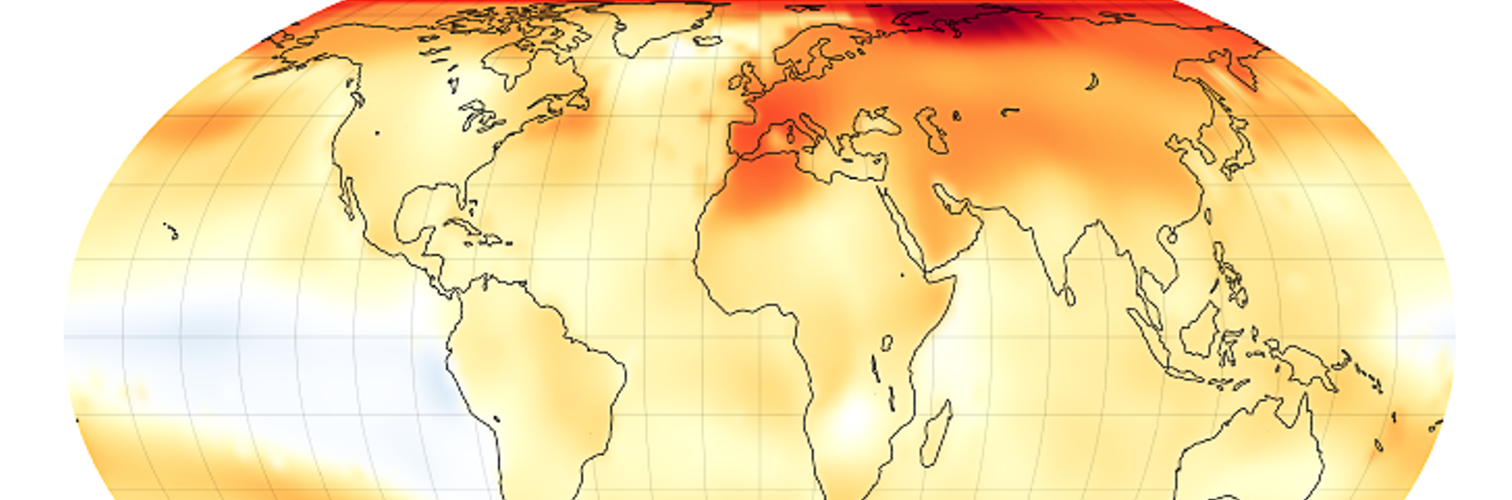

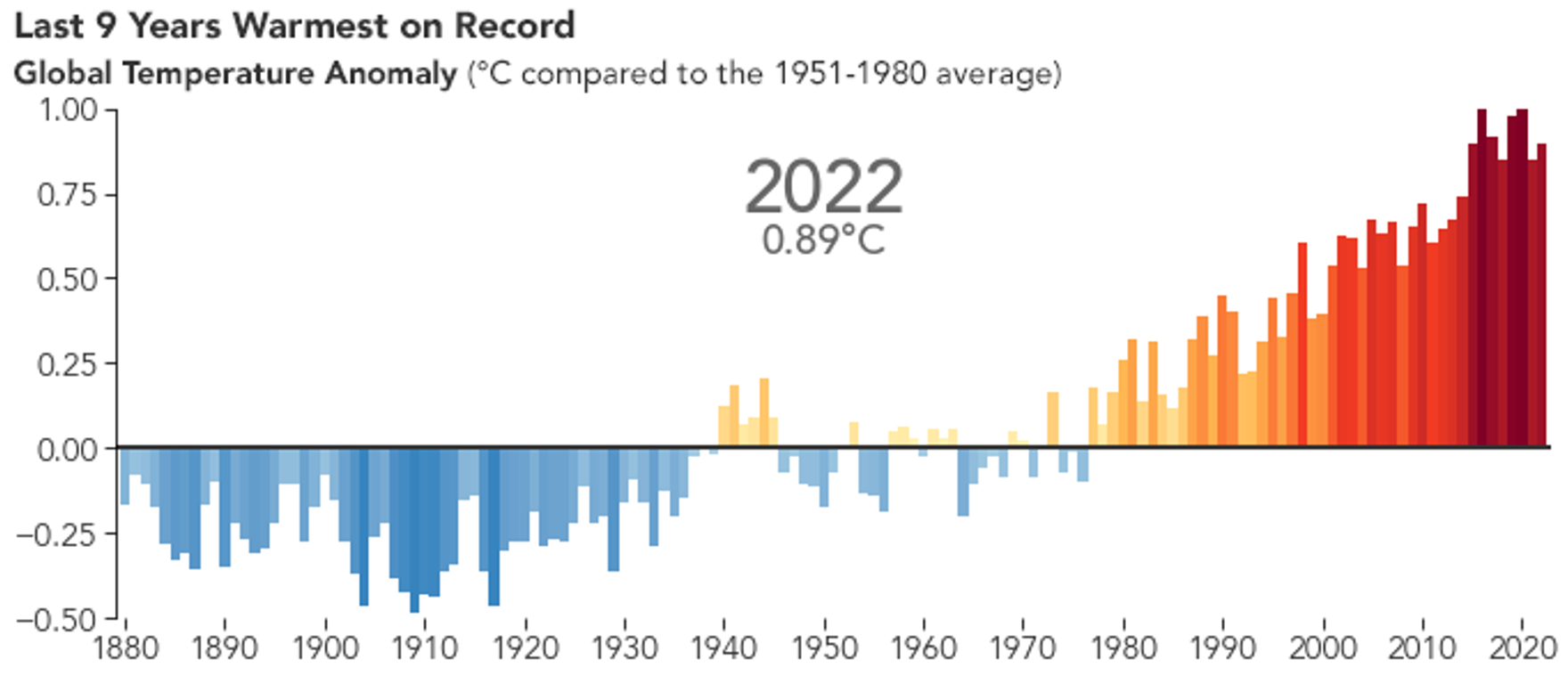

The latest data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) pegs the annual inflation rate for food running at 6.8%. Concern with global warming accelerated during 2021, from the halls of international organizations and national governments all the way to the farm gate.

Concern with global warming accelerated during 2021, from the halls of international organizations and national governments all the way to the farm gate. Department of Agriculture projections for FY2021 indicate

Department of Agriculture projections for FY2021 indicate

2021 helped drive home an important truth: farming is a technology-dependent activity. Better technology can offset labor issues and enable the better productivity and operational efficiency critical to solid bottom lines.

2021 helped drive home an important truth: farming is a technology-dependent activity. Better technology can offset labor issues and enable the better productivity and operational efficiency critical to solid bottom lines.  Joey Chestnut routinely grabs headlines when he wins the annual July 4th Nathan’s Hot Dog Eating Contest. This year was no different when the 37-year-old American scarfed down 76 hot dogs (and buns) in 10 minutes to win for the 14th time in his career. Less noted: Women’s champion Michelle Lasco managed to down 30 and ¾ hot dogs in the same time span. Yup, together that’s nearly 100 hot dogs in 10 minutes. It’s also close to 29,000 calories – or over 10 times the daily caloric intake of the typical person. Is this a great country, or what?

Joey Chestnut routinely grabs headlines when he wins the annual July 4th Nathan’s Hot Dog Eating Contest. This year was no different when the 37-year-old American scarfed down 76 hot dogs (and buns) in 10 minutes to win for the 14th time in his career. Less noted: Women’s champion Michelle Lasco managed to down 30 and ¾ hot dogs in the same time span. Yup, together that’s nearly 100 hot dogs in 10 minutes. It’s also close to 29,000 calories – or over 10 times the daily caloric intake of the typical person. Is this a great country, or what? A Brazilian cow, unhappy with its prospects as a future delicious dinner, escaped and sought safety in a nearby water park, where it managed to take one last fling at fun by sliding down the park’s lengthy waterslide into the cool and refreshing pool below. Officials reportedly denied the fun-seekers request to “do it again, do it again…” but the happy animal was given a consolation prize of spending the remainder of what we all hope will be a long and happy life courtesy of a kind-hearted rancher 500 miles west of Rio de Janeiro. And BTW, the cow’s new name: Toboga, Portuguese for “waterslide.”

A Brazilian cow, unhappy with its prospects as a future delicious dinner, escaped and sought safety in a nearby water park, where it managed to take one last fling at fun by sliding down the park’s lengthy waterslide into the cool and refreshing pool below. Officials reportedly denied the fun-seekers request to “do it again, do it again…” but the happy animal was given a consolation prize of spending the remainder of what we all hope will be a long and happy life courtesy of a kind-hearted rancher 500 miles west of Rio de Janeiro. And BTW, the cow’s new name: Toboga, Portuguese for “waterslide.” The fine folks in Austin, Minnesota, for years, have enthusiastically observed the glories of the pork delicacy SPAM, with parades, cookouts, and sundry celebratory events. Dirt to Dinner actually has attended this august event and can honestly report it to be one of the finest examples of true Americana anywhere. But we also must note that word has spread about another “Spam Jam” – this version found on Waikiki in Hawaii, where 7 million cans of Spam are consumed each year as a self-proclaimed “cultural tradition.” Cans of the pork delicacy are donated to local food banks if that helps explain the event’s real allure. Let’s ALL go…

The fine folks in Austin, Minnesota, for years, have enthusiastically observed the glories of the pork delicacy SPAM, with parades, cookouts, and sundry celebratory events. Dirt to Dinner actually has attended this august event and can honestly report it to be one of the finest examples of true Americana anywhere. But we also must note that word has spread about another “Spam Jam” – this version found on Waikiki in Hawaii, where 7 million cans of Spam are consumed each year as a self-proclaimed “cultural tradition.” Cans of the pork delicacy are donated to local food banks if that helps explain the event’s real allure. Let’s ALL go…

The film is well-intentioned. It covers core global issues we currently face across nine defined boundaries. It highlights the importance of individual action and response.

The film is well-intentioned. It covers core global issues we currently face across nine defined boundaries. It highlights the importance of individual action and response. It is vital to offset the carbon we will inevitably emit (at least to some level).

It is vital to offset the carbon we will inevitably emit (at least to some level).

Similar to the

Similar to the

An elementary step we can make at home is reusing water bottles. It seems obvious, but the cumulative statistics are staggering.

An elementary step we can make at home is reusing water bottles. It seems obvious, but the cumulative statistics are staggering.

Drought affects both crop and livestock production, obviously. Dealing with the problem poses different sets of problems and issues for both.

Drought affects both crop and livestock production, obviously. Dealing with the problem poses different sets of problems and issues for both.

AgMission thinks so. If all the farmers in the United States adopted soil-smart farming systems such as no-till, cover crops, rotational grazing, manure management, methane-reducing animal feed, and variable-rate fertilizer application, then the soil would be healthier and more carbon would be pulled from the atmosphere.

AgMission thinks so. If all the farmers in the United States adopted soil-smart farming systems such as no-till, cover crops, rotational grazing, manure management, methane-reducing animal feed, and variable-rate fertilizer application, then the soil would be healthier and more carbon would be pulled from the atmosphere.

While the focus on climate change comes as no surprise, the farm community anxiously awaits some sign of the approach to be taken. Farm leaders urge policymakers to think in terms of carrots rather than sticks. That is, they note that the farm community by and large is supportive of the broad effort to act responsibly on matters that affect the climate, and the environment.

While the focus on climate change comes as no surprise, the farm community anxiously awaits some sign of the approach to be taken. Farm leaders urge policymakers to think in terms of carrots rather than sticks. That is, they note that the farm community by and large is supportive of the broad effort to act responsibly on matters that affect the climate, and the environment.

Continuing economic challenges from the pandemic, coupled with a generally more ambitious agenda of government initiatives, mean an almost certain review and revision of tax laws. It will likely involve examining a range of tax policies, including capital gains, gift taxes, inheritance taxes, accounting rules, and more.

Continuing economic challenges from the pandemic, coupled with a generally more ambitious agenda of government initiatives, mean an almost certain review and revision of tax laws. It will likely involve examining a range of tax policies, including capital gains, gift taxes, inheritance taxes, accounting rules, and more.