After years of serious debate about the reality or extent of actual climate change, governments around the world have responded to rising public support for “green” policies and programs.

For the United States, it’s a 2021 pledge by President Biden in the Paris Climate Accord to cut GHG emissions in half by 2030. Biden’s ambitions continue for the United States by stating that we will reach 100% carbon pollution-free electricity by 2035 and net-zero emissions economy by 2050, just 26 years from now.

International leaders also speak of commitments to massive greenhouse gas (GHG) reductions by mid-century, and businesses around the world have jumped on the prevalent environmental bandwagon with ambitious GHG reductions of their own. But things have changed since the glory days of the Paris Accord.

The subject of climate change has had sufficient time to percolate in the public mind. The issue has moved on from an initial era of awareness-building – years of helping define the issue in the public mind and marshaling political support for ambitious targets and extensive policies and programs. We now appear to be entering the next stage of public discussion and debate, focusing on the practical realities of moving the issue from an abstraction to reality.

As more and more of the policies and programs initiated in the undoubted enthusiasm for a better environment begin to gain traction, people are beginning to ask questions – sometimes difficult questions.

The Evil of Fossil Fuels

The largest area of concern centers on the extent of our dependence on fossil fuels. We’ve successfully created the picture of a self-destructive reliance on an energy source that is deemed to be harmful to the environment and to people. It’s so bad, critics argue, that we have no choice but to embrace draconian actions that effectively cut our use of fossil fuels – and cut it now rather than later.

Reduced use of petroleum products in the transportation industry and generation of electricity is a key objective, as is the development and use of other non-fossil fuel energy sources, including such renewable sources as solar, tidal, biofuels and wind. In short, transforming it fundamentally transforms our entire energy system.

According to 2022 government data, nearly 80% of U.S. energy consumption comes from fossil fuels, with the country consuming almost 20.3 million barrels of petroleum, about a fifth of the global total, every day.

The best-intentioned efforts, however, have proven to have some sobering realities. The largest of those realities is the sheer scale of the challenge. We have built an enormous economy on the basis of fossil fuels. Our gross domestic product is now roughly $25.5 trillion. Retooling such an economic engine away from dependence on fossil fuels will take money – a lot of money – not to mention the time needed to make such a transition without sending the economy into a tailspin.

Proponents of aggressive change believe that the huge costs of transformation will indeed lead to short-term run-up in consumer costs, as the price for new technologies and equipment and support systems come into play.

However, over time, they argue that these price-run-ups will be offset by improved efficiencies and lower costs that come from moving to a low-carbon energy model.

Analysis by leading consulting organizations echo this argument. But those same consultants also acknowledge that the cost of transitioning to net-zero emissions of GHG by 2050 will cost an extra $3.5 trillion per year. Cynics pointedly ask for an example of cost reductions actually being passed back to consumers, once the increases have been implemented.

Who Pays?

The question of “who pays” has become an increasingly troublesome matter to more than energy consumers. The food and agriculture sector is not immune to the economic questions posed by the wide range of green policies and regulations imposed in the name of protecting people and the planet.

The most immediate issue raised by people across the food chain is the enormous role played by energy costs in producing commodities and food products. Farming and ranching have massive energy needs and agriculture contributes approximately 11% of global green house gas emissions.

Nitrogen fertilizers are derived primarily from natural gas and make up one of the most critical crop inputs and remain a key to productivity. Field equipment such as tractors, combines, and trucks demand fuel, as well as power for moving, storing, drying, and maintaining crops. Basic processing of commodities into the food ingredients used by food manufacturers also demands significant energy. Warehousing and distribution of food to retailers and restaurants is inherently transportation-dependent.

Moving to vehicles not dependent on fossil fuels is a noble objective. But once again, the reality is that such a transformation in a system as large as the U.S. food system will be an expensive proposition. The more rapid the required conversion, the higher the risk of short-term adverse effects on the producer bottom-line.

Moving to vehicles not dependent on fossil fuels is a noble objective. But once again, the reality is that such a transformation in a system as large as the U.S. food system will be an expensive proposition. The more rapid the required conversion, the higher the risk of short-term adverse effects on the producer bottom-line.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates that our national food system accounts for 12.5 percent of U.S. energy use (2012). Between 1998 and 2002, more than half of the increase in U.S. energy use came from the food system, USDA noted.

If you want the gee-whiz numbers this represents, consider an estimate from USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS) that found the U.S. food system consumed about 12 quadrillion British Thermal Units (BTUs) in 2012. Each of those 12 quads works out to the energy in about 8 billion gallons of gasoline, or 293 billion kilowatt hours of electricity., or 36 million tons of coal. No matter how detailed or debatable the conversion arithmetic, that’s a lot of wind turbines and solar panels.

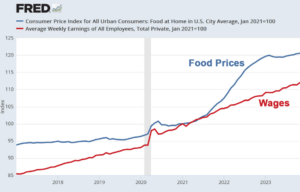

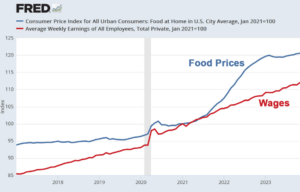

Food inflation has averaged roughly 3.2 percent each year for most of the past century. A host of factors during the Covid pandemic converged to drive food inflation to 6.3 percent in 2021 and a whopping 10.4 percent in 2022. (Inflation rates in other parts of the world remain elevated as well. In the European Union, for example, food inflation peaked in mid-2023 at 19 percent before dropping to “only” 5.9 percent by year’s end.)

Cutting through all the numbers leaves one clear message: consumer food costs remain under considerable inflationary pressures for multiple reasons. Energy costs – and the immediate transitional costs imposed by a growing roster of green requirements – will help maintain these pressures.

Cutting through all the numbers leaves one clear message: consumer food costs remain under considerable inflationary pressures for multiple reasons. Energy costs – and the immediate transitional costs imposed by a growing roster of green requirements – will help maintain these pressures.

Post Covid, the inflation rate has dropped back to more traditional rates. But the rising concern with further disruptions to global energy markets – and the unrelenting cost pressures on producers and others across the food chain from green policies and other cost sectors – once again have people looking a bit nervously over their shoulders about future food costs.

Green Politics

The worry over continuing food inflation – and the possible role of green policies in fueling that pressure – have taken root across many of the countries at the heart of the Paris Climate Accord and their ambitious targets for moving to a more carbon-neutral global energy system.

The issue has prompted vocal protests and confrontational demonstrations from European and UK farmers – and generated rising concern among the elected officials who must reconcile those protests with existing and planned green commitments.

EU and UK farmers argue they are being squeezed on a number of economic fronts. Shifting marketing flows in the wake of the Ukraine conflict have increased supplies, with resultant price pressure on commodities. The Middle East is fraught with conflict and the future is uncertain in regard to oil prices. Cuts in diesel subsidies and other energy-related supports have added to costs and hurt producer bottom lines, German farmers contend. Restrictions on nitrogen-based fertilizers and sequestration of some farmlands have hurt productivity and profitability, others argue.

Complying with a growing roster of green requirements involves ever-more bureaucracy and takes more and more time and expense. Protests have spread across France, Germany, Spain, Romania, Poland, Greece, Portugal, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom.

As one farmer summed up the litany of complaints to CNN, “We are no longer making a living from our profession.”

Eurostat findings tends to support the complaint: data shows a nearly 9 percent drop in the prices paid to EU farmers from 2022 to 2023.

Put that in perspective by imagining what you would do with that drop in your own household income – especially in an inflationary period.

The protests have reached sufficient size to prompt elected officials – many facing autumn elections – to rethink the extent and, perhaps more importantly, the timing of the ambitious green agenda. Some changes and restrictions have been rolled back or delayed. At this time, the discussion seems to focus on getting farmers more involved in the planning and development of green policies and programs and looking at time frames that provide greater opportunity for transition and adaptation.

European Commission President U chief Ursula von der Leyen has given up on an ambitious bill to reduce the use of chemical pesticides and softened the European Commission’s next raft of recommendations on cutting agricultural pollution. “We want to make sure that in this process, the farmers remain in the driving seat,” she said at the European Parliament. “Only if we achieve our climate and environmental goals together will farmers be able to continue to make a living.”

Evolutionary reality seems to be gaining traction over economically revolutionary good intentions.

Back in the U.S.

U.S. policy-makers still debating a massive long-term Farm Bill aren’t ignoring what is going on in the EU on the farm front. Many of the concerns and complaints heard across Europe and the UK sound all too similar to what U.S. producers may be thinking and saying.

Consumer attitudes also come into political play. Current estimates place the U.S. inflation rate at 3.5 percent, down significantly from the 7 percent and 6.5 percent seen in 2021 and 2022 but up slightly from last year’s 3.4 percent. Energy and food inflation, however, remain well above this level and represent two of the most powerful drivers of the cost increases facing consumers in the United States and elsewhere around the globe. Inflation hits hard. The other day in the grocery store, we overheard a child asking for a watermelon and his mother said no, at $7 it is too expensive. Sensitivity to those points of view grows especially strong as November looms.

How other countries handle the economic and political realities of ‘going green’ may offer some important advice on how to make that transition acceptable to everyone – none the least the American farmers and ranchers worried about their financial security, or the average food consumer tired of unrelenting increases in the costs of feeding their families.

Moving to vehicles not dependent on fossil fuels is a noble objective. But once again, the reality is that such a transformation in a system as large as the U.S. food system will be an expensive proposition. The more rapid the required conversion, the higher the risk of short-term adverse effects on the producer bottom-line.

Moving to vehicles not dependent on fossil fuels is a noble objective. But once again, the reality is that such a transformation in a system as large as the U.S. food system will be an expensive proposition. The more rapid the required conversion, the higher the risk of short-term adverse effects on the producer bottom-line.