As a younger parent, I was perpetually annoyed hearing things like, “Once you hit 40, it all goes downhill…and fast” That’s not due to age, I thought; that’s from life’s circumstances – kids, aging parents, job shifts, and so on.

And then I got there. For months, I felt like I was losing the battle against fatigue while somehow acquiring jitters with my second cup of coffee. Then I came across an article in the medical journal Nature, which felt like a harsh yet validating slap in the face. I guess there is something to this sudden shift in aging once we hit 40s, after all…

We all know aging is unavoidable – a constant in our lives once we reach our mid-30s. But while most of us naively liken it to a slightly uphill stroll, a recent study reveals that aging sneaks in a couple of surprising hairpin turns along the way, most likely occurring in our 40s and again in our 60s.

Sure, these shifts may be biological, but there must be things we can do to ease these blows, right? Thankfully, yes…but let’s get the basics of this study down first.

Overview of the study

The study, Nonlinear Dynamics of Multi-omics Profiles During Human Aging, takes a comprehensive look at how molecular and biological processes shift over time, offering insight into how our bodies age and which factors significantly affect our long-term health, lifestyle, and nutrition during these periods.

The Stanford University research team followed 108 California residents between the ages of 25 and 75 over an average period of 2 years. They collected massive amounts of “multi-omics” data – large sets of biological information to measure molecular activity in the body.

This comprehensive series of tests does more than just track blood pressure or glucose levels; it captures hundreds of various body functions for an individual, all at the molecular level. Multi-omics data for this study included the following lab tests:

- Genomics: genes, or DNA; essentially the body’s instruction manual

- Transcriptomics: RNA, shows which genes are “turned on” or active

- Proteomics: proteins that carry out most of the body’s functions, including cytokine activity

- Metabolomics: metabolites, or the small molecules made when your body breaks down food, drugs, or its own tissues

- Lipidomics: fats and fatty molecules that play key roles in energy and cell structure

- Microbiomics: microbes living in and on you that affect digestion, immunity, and mood

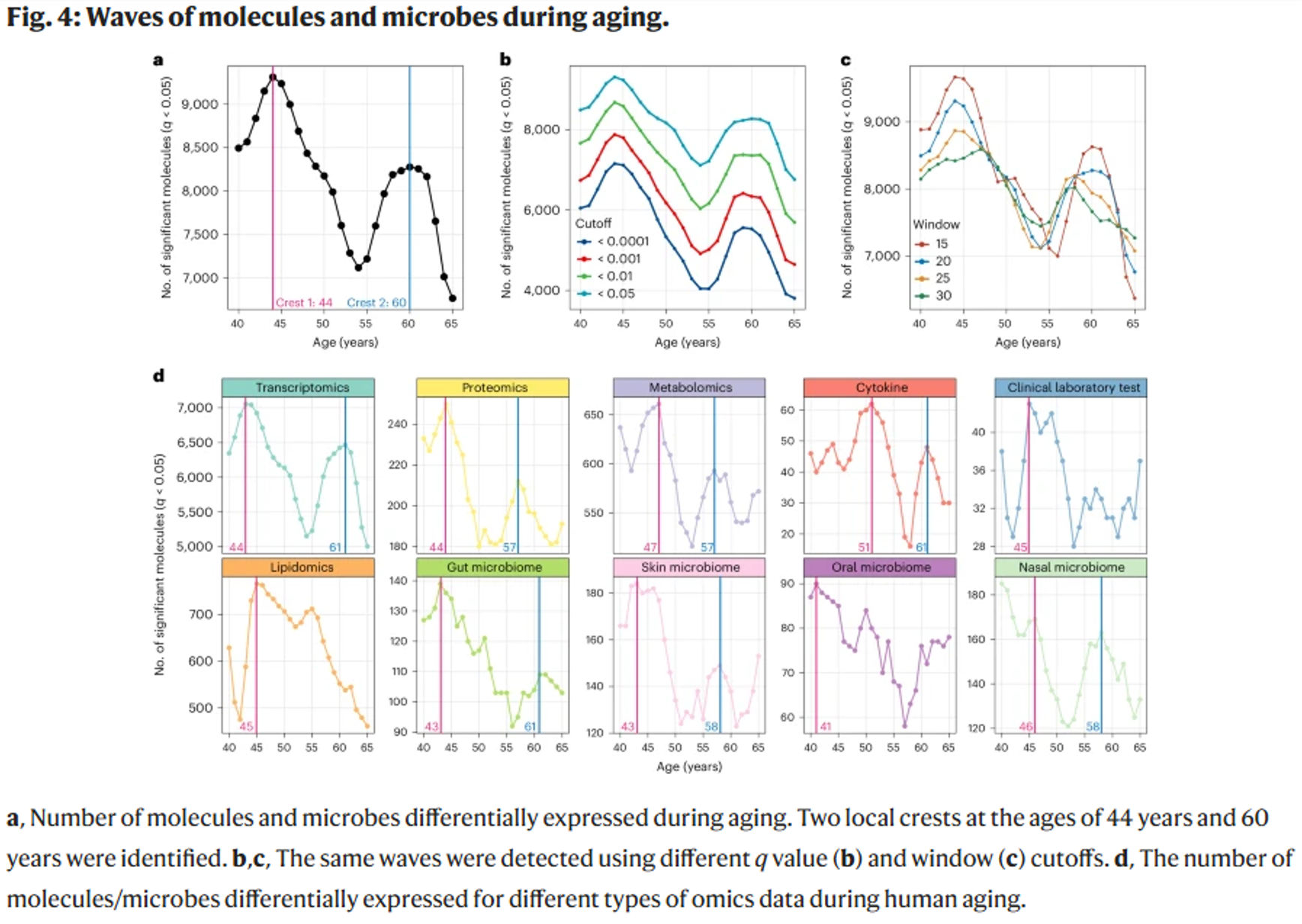

Rather than the collected data showing linear molecular changes over time, researchers found the opposite: most of the changes are non-linear.

In fact, only about 7% of all molecular activity studied behaved linearly with age, whereas about 80% of molecular behavior revealed far more complex, non-linear patterns.

What does “non-linear” really mean here?

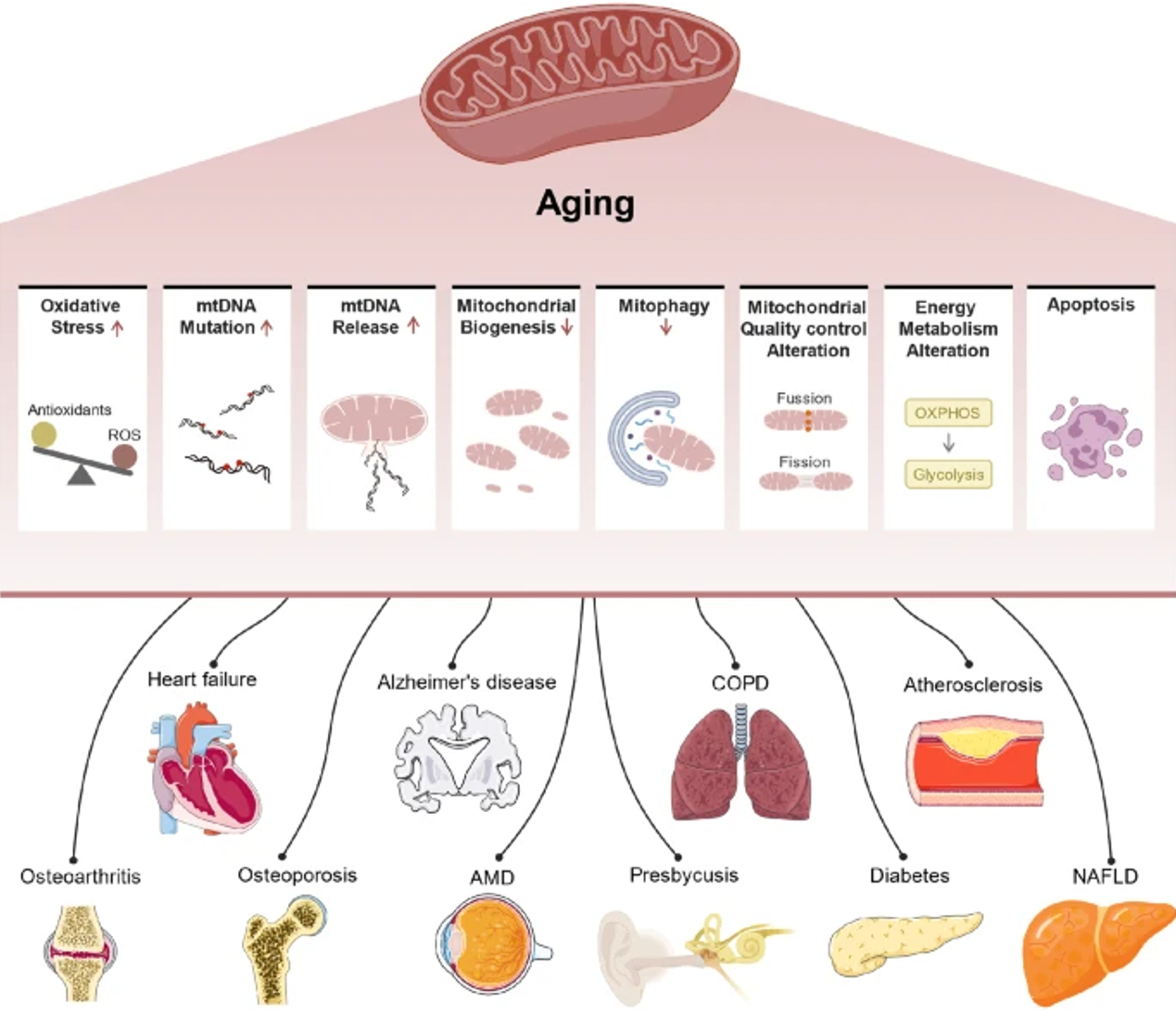

This study suggests our body’s molecular and functional “engine” doesn’t slow down gradually; it hits two major inflection points. These two major “waves” are represented in the data as significant periods of molecular disruption, occurring around ages 44 and 60.

The multi-omics data indicates that each wave is unique regarding specific changes occurring in our bodies:

Around age 44:

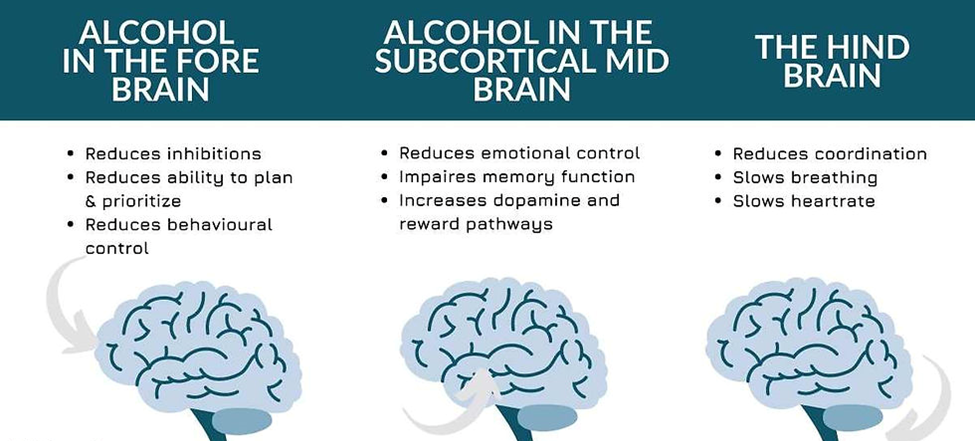

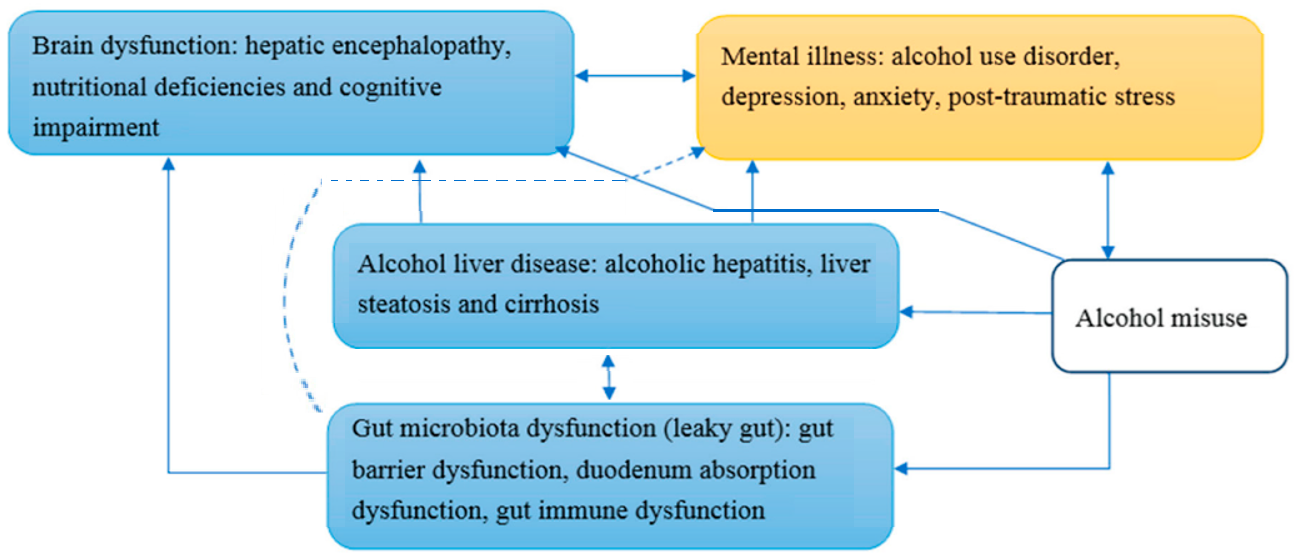

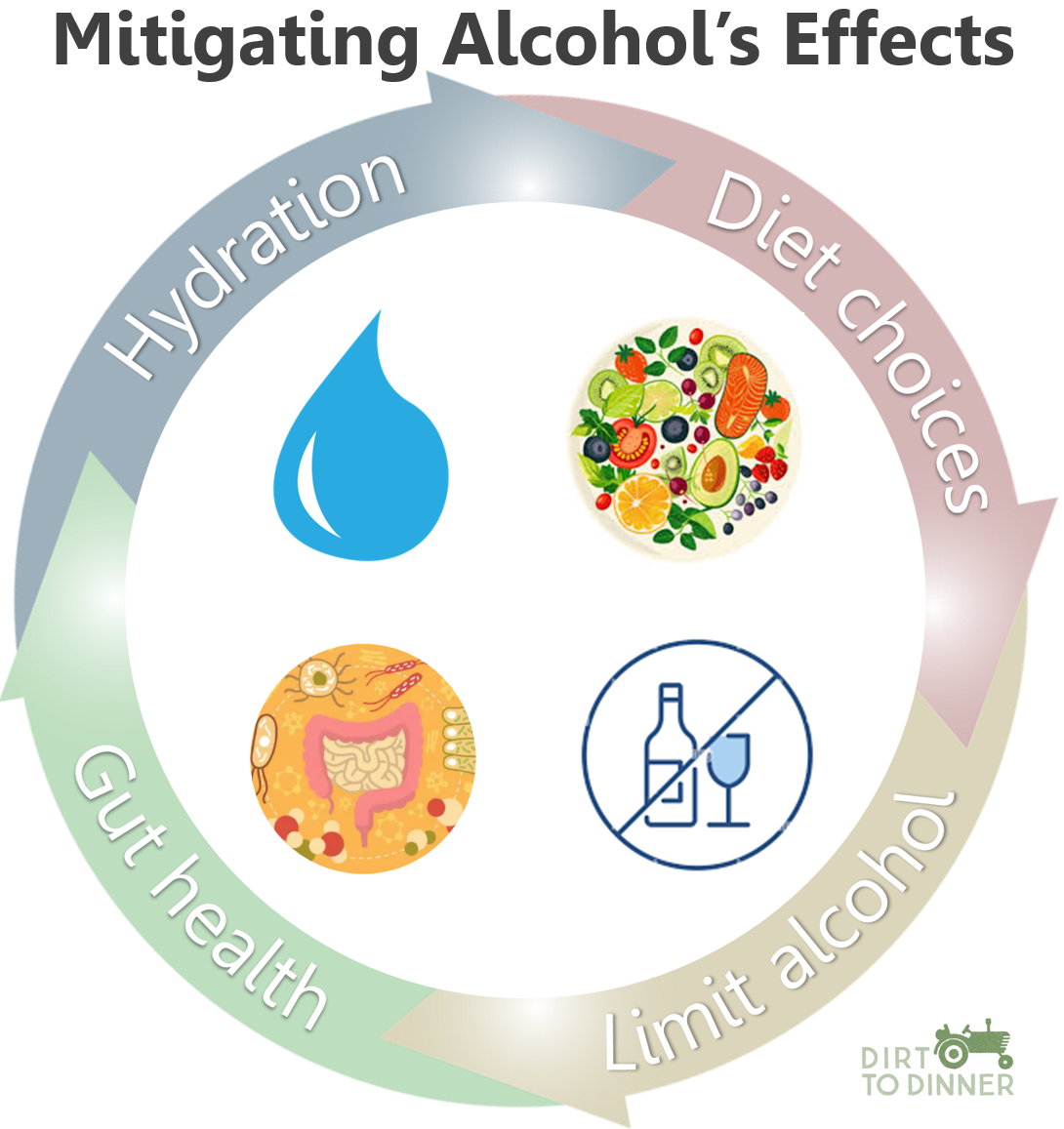

- Molecular activity: significant molecular disruptions occur in lipid metabolism, alcohol metabolism, caffeine metabolism, and cardiovascular/lipid markers

- Observations: marked decreases in metabolism, energy, and cardiovascular health indicate extra attention needed at this stage

The takeaway: Your body can’t break down fats for energy or metabolize alcohol or caffeine as well. In addition, exercise more frequently to keep your heart healthy.

Around age 60:

- Molecular activity: significant shifts occur in immune regulation, carbohydrate and fat metabolism, kidney function, tissue and organ structural stability

- Observations: the body’s immune system begins to change, blood sugar control can become trickier, and tissues such as muscle and skin may lose resilience

The takeaway: Be kind to your body and diversify your microbiome during this phase, as your immune system and metabolism aren’t as efficient. Also, your kidneys and other organs are less resilient, so stay hydrated all day long.

How did researchers detect these shifts?

Scientists wanted to see how different molecules and microbes in the body shift as we age, so they used a computer algorithm called DEswan, which is like sliding a magnifying glass along the subjects’ molecular timeline. This helped them distribute people into similar age groups to spot where big shifts happened in the body’s chemistry and microbiome from one age group to the next.

When they looked at all the compiled data, that’s when they discovered these molecular changes coming in distinct waves.

When they looked at all the compiled data, that’s when they discovered these molecular changes coming in distinct waves.

And these waves correspond with age-related illnesses, like the accelerated risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and kidney disease during these inflection periods.

Though this study has been peer-reviewed, the researchers note some limitations that may not align with the broader population.

They note the relatively small cohort of 108 subjects, all aged 75 or younger and residing in California. Also, data collection was limited to about two years, whereas most aging studies are longitudinal, providing multiple years of data to mine for more concrete findings.

What can be done to slow down aging?

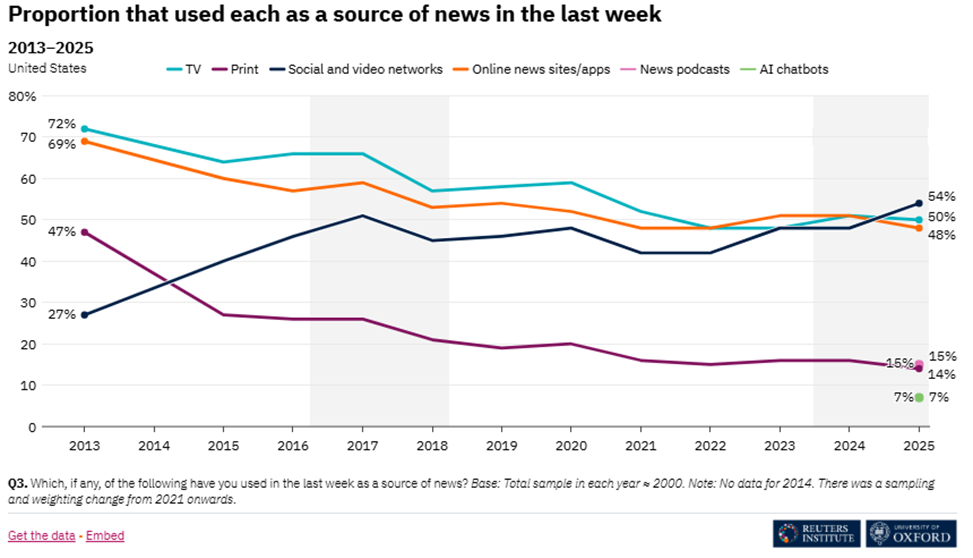

We often turn to social media feeds and other news sources to provide us with health and wellness solutions, especially when we see excerpts from well-known anti-aging professionals. These experts often include Dr. Peter Attia and his recent book, Outlive; Dr. Rhoda Patrick’s research on inflammation and aging; and Dr. Andrew Huberman’s conversations with fellow longevity experts, like biologist David Sinclair.

But what have studies shown us about slowing down our biological age? While more research is being conducted on the molecular indications of humans’ biological aging, here are a few studies that have shown promise in slowing down its process via our lifestyle choices, with technology potentially playing a role further down the pipeline, too.

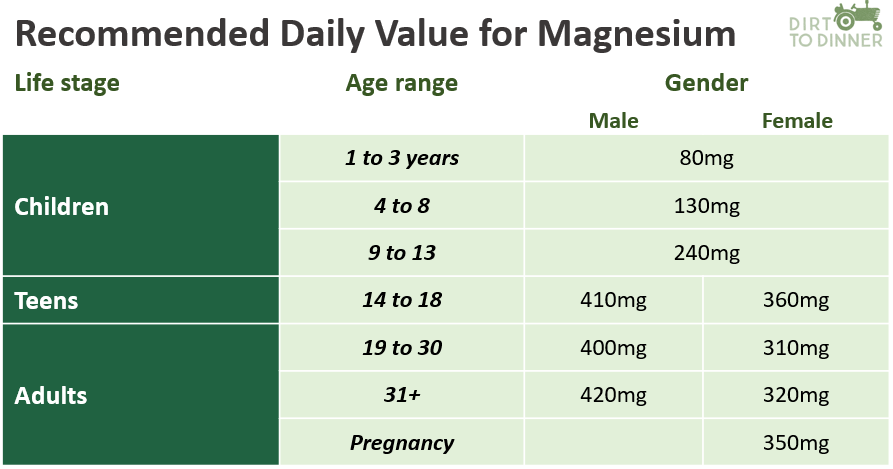

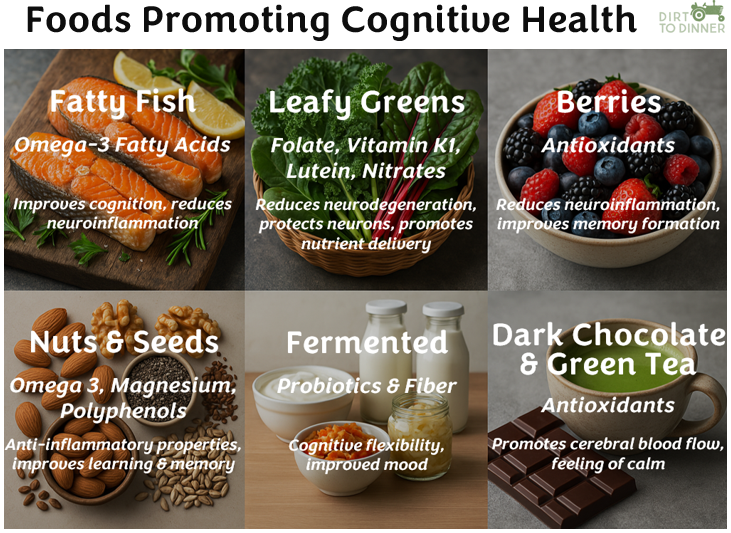

A recent study with older adults revealed the surprising impact just three things can have on aging. Subjects who took omega-3 fatty acids and vitamin D and exercised regularly experienced a measurable slowing of biological aging, or about 3.5 months [ls3] [HK4] over three years, according to the researchers’ epigenetic clock measurements.

A meta-analysis on calorie-restricted eating studies shows that reducing caloric intake by 25% can slow our biomarkers of aging, leading to a reduction in future mortality risk. Intermittent fasting yields similar results, as well.

And ongoing research into epigenetics continues to reveal all the small ways our lifestyle and everyday behaviors can affect how our genes are expressed, including how we biologically age. Our DNA is affected by everything we experience – from the chemicals released from activity, during periods of stress, foods and drinks we consume, the quality of our sleep, and so on. So while we inherit our genes, it’s our lifestyle that helps turn them on or off.

Novel therapies in biotechnology may further slow down aging in the coming years. Recently, scientists have found that senescent cells – aged cells no longer functioning properly – can be cleared by drugs or supplements called senolytics, which helps preserve tissue integrity and reduce inflammation. And clinical trials investigating epigenetic reprogramming have found that some cells can be “reset” to help regenerate tissues and repair damage.

While we may not “stop” aging altogether, we’re gaining tools to shift the pace and perhaps extend the period of life spent in good health. But the insight from current research is actionable: aging biology is dynamic, and our behaviors can interact with that.

Tips for planning long-term health

There’s a lot of heavy information here – I know. But keep in mind that these “waves” should be used as gentle reminders for our intervention, rather than ticking time bombs.

So try to replace any doomscrolling with these helpful tips instead:

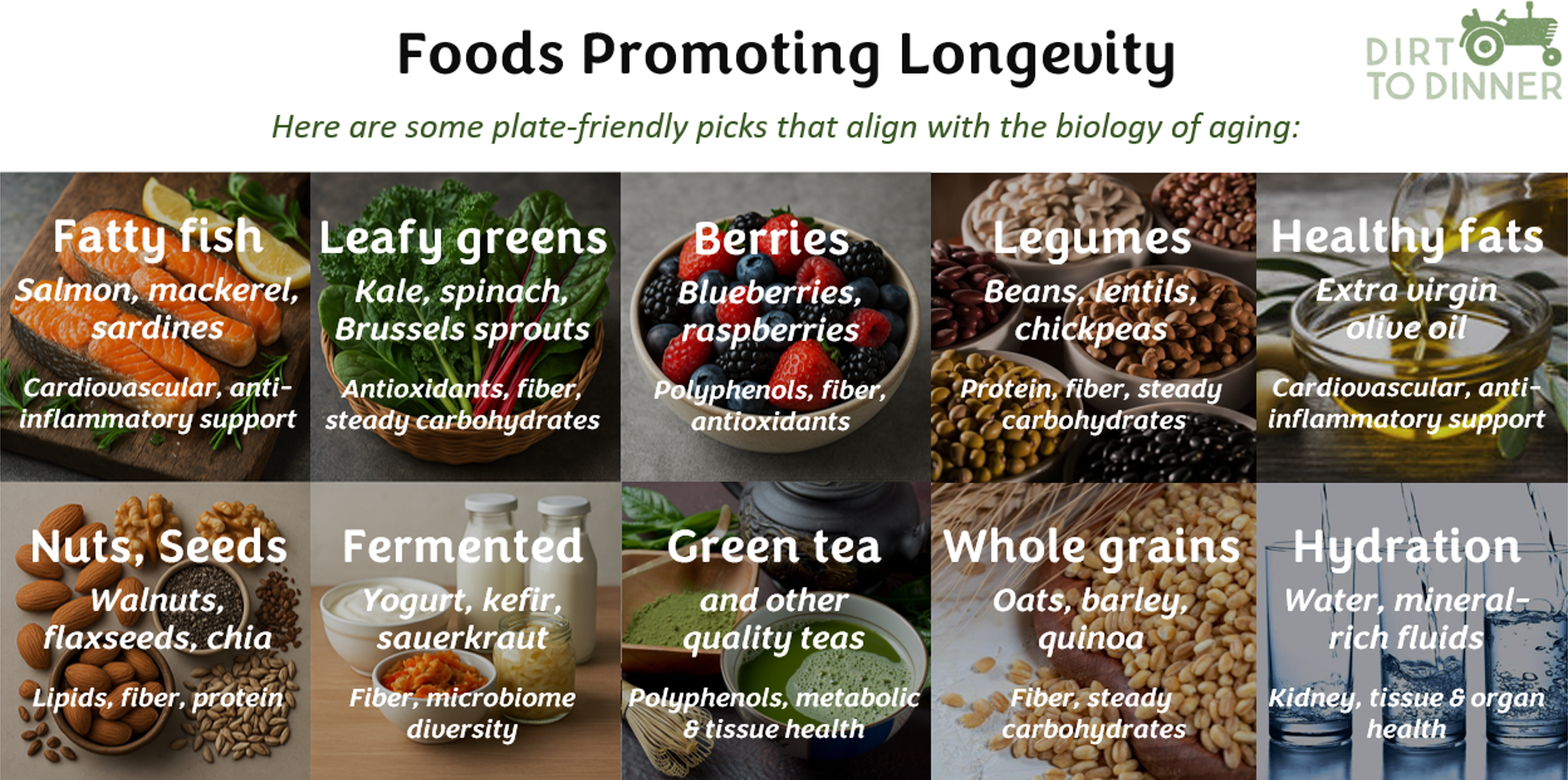

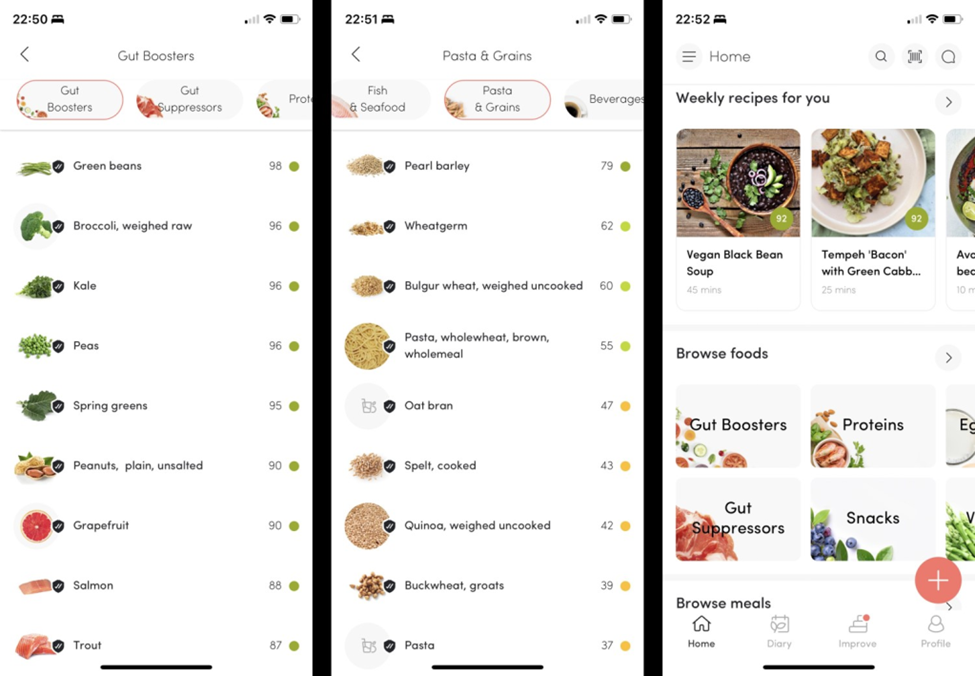

- Follow a gut-healthy diet

- The food-microbiome link is especially important to temper these molecular disruptions affecting metabolite, lipid, and protein functioning.

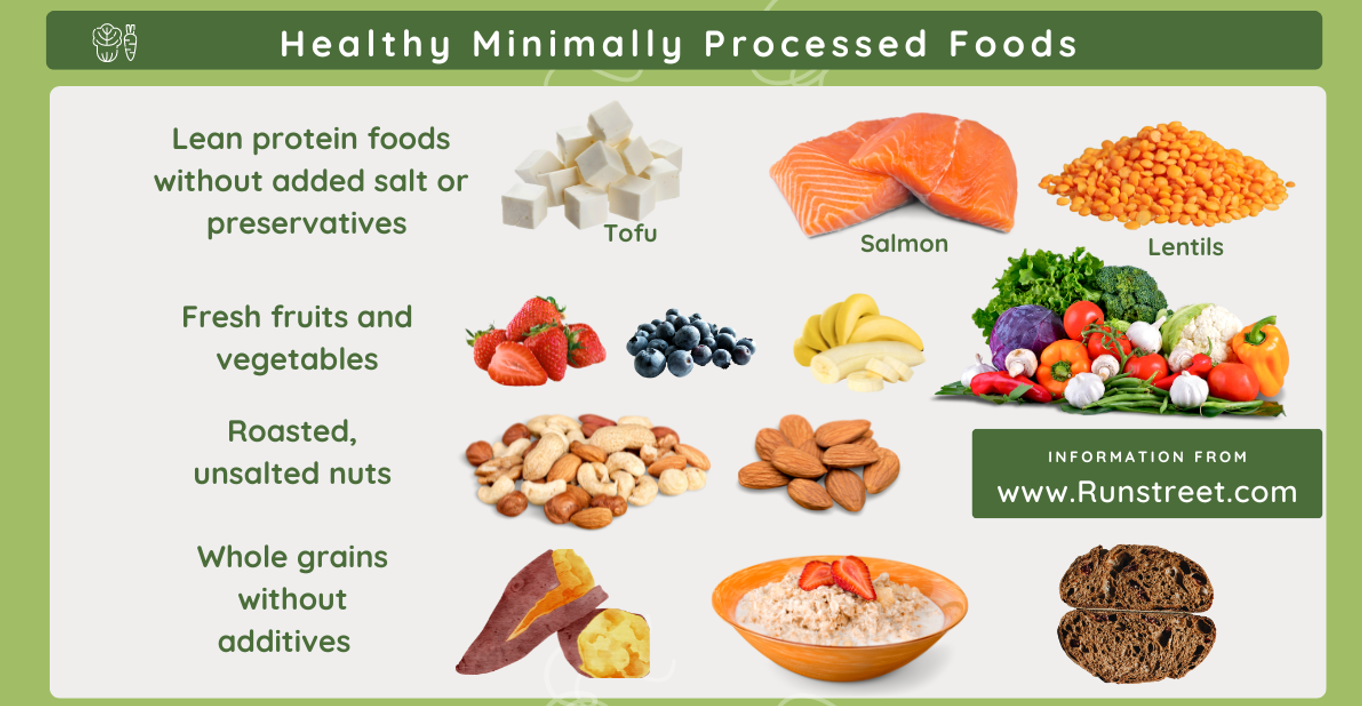

- A diet rich in fiber, diverse plants, lean proteins, and fermented foods can influence multiple aging pathways.

- It’s never too late to adopt a “longevity-friendly” lifestyle

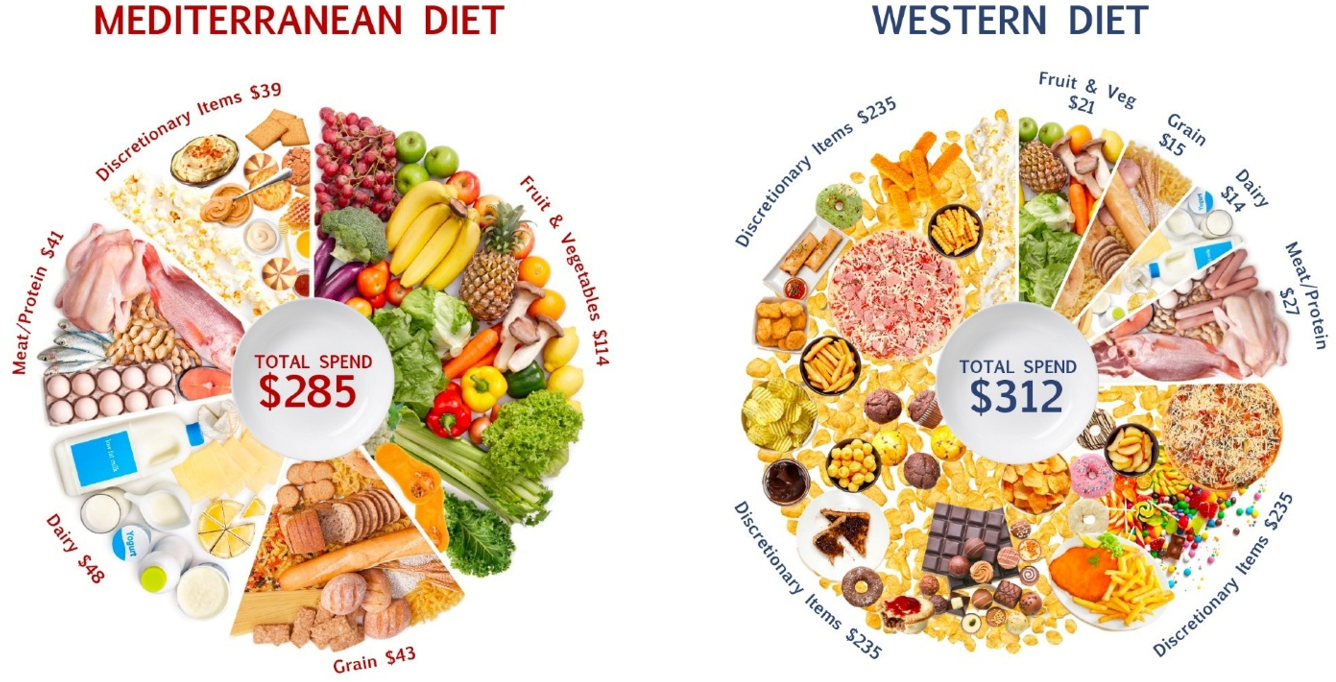

- Consider adopting a healthier approach to your eating habits, such as adhering to the Mediterranean diet and/or trying intermittent fasting

- If you’re on the younger side, your 30s and 40s are an ideal time to build strength in metabolic flexibility by increasing muscle mass, cardiovascular resilience, and decreasing consumption of saturated fats, alcohol, and caffeine

- As you move into your 50s and beyond, focus on resistance training and light to moderate exercise several times a week, and consume immune-supporting fruits and veggies, lean proteins, kidney-friendly hydration, and anti‐inflammatory add-ins

- Don’t forget these crucial habits, too:

- Exercise, sleep quality, stress management, activity level, and daily habits all feed into the molecular systems that the study highlights, like our immune system, metabolism, and tissue integrity

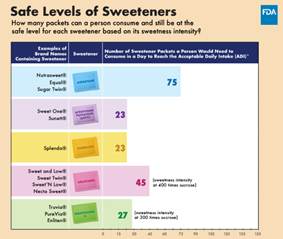

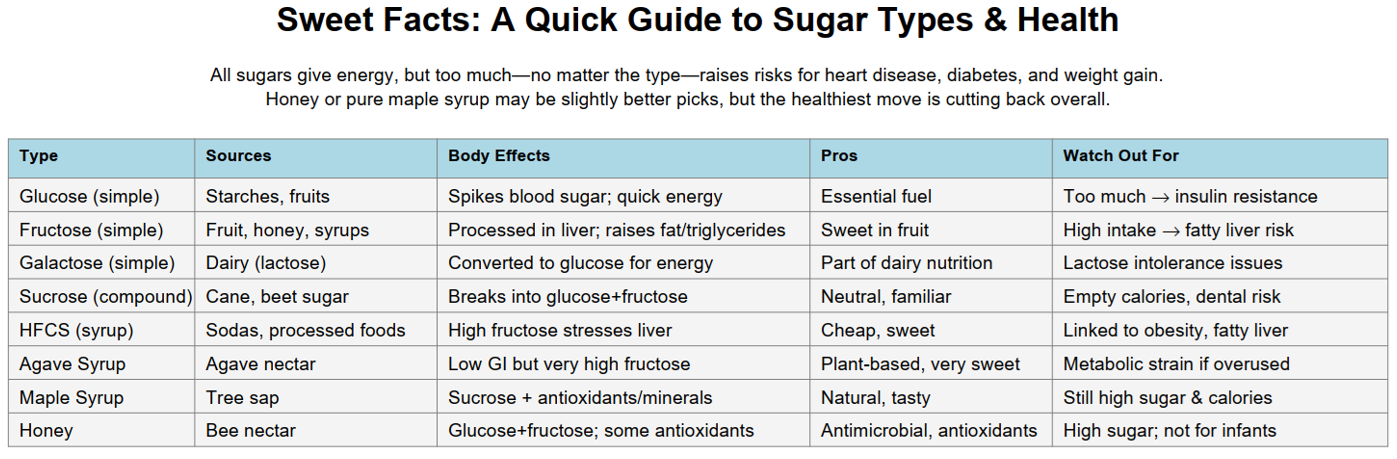

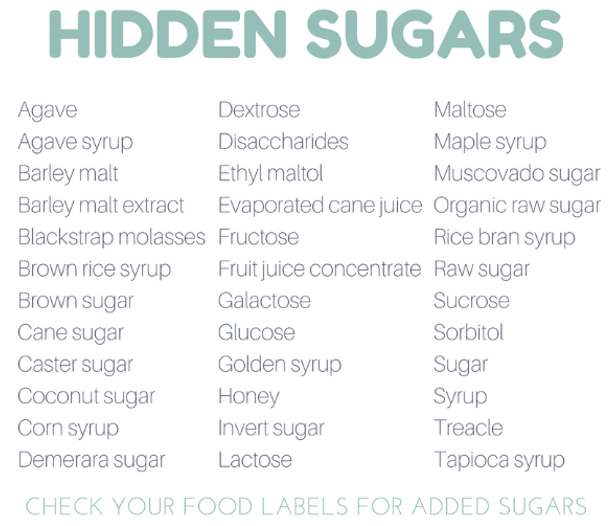

- Limit consumption of alcohol, highly processed meats, sodas, and other products with excessive added sugars, as these can increase molecular disruption

While still true, these guidelines often fail to capture the complexity of human biology—and the individuality of how we metabolize food.

While still true, these guidelines often fail to capture the complexity of human biology—and the individuality of how we metabolize food.

Emerging platforms

Emerging platforms

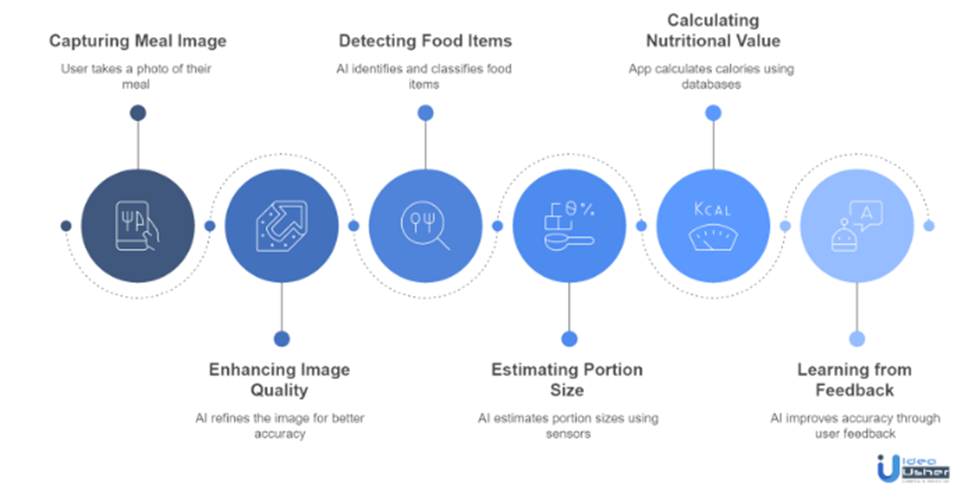

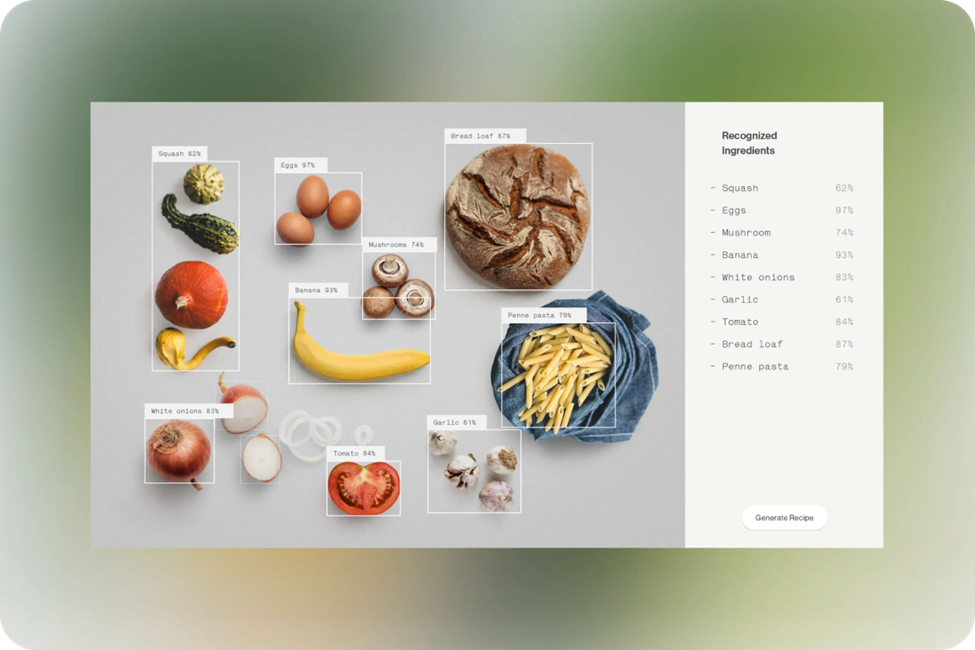

Samsung Food’s Vision AI easily scanned items in my fridge, sometimes correctly identifying even partially used produce, and generated recipes that incorporated what I already had on hand. It wasn’t perfect (a few mystery leftovers stumped it), but the suggestions often saved me from another night of takeout.

Samsung Food’s Vision AI easily scanned items in my fridge, sometimes correctly identifying even partially used produce, and generated recipes that incorporated what I already had on hand. It wasn’t perfect (a few mystery leftovers stumped it), but the suggestions often saved me from another night of takeout.

Advocates claim it reduces inflammation, improves mental clarity, and helps manage glucose levels, and promotes weight loss. However, the reported benefits of this diet are more anecdotal than clinical. In fact, multiple studies cite the dangers of this diet, including

Advocates claim it reduces inflammation, improves mental clarity, and helps manage glucose levels, and promotes weight loss. However, the reported benefits of this diet are more anecdotal than clinical. In fact, multiple studies cite the dangers of this diet, including

For instance, high consumption of saturated fats like beef tallow – which

For instance, high consumption of saturated fats like beef tallow – which  Yes, ACV can slightly

Yes, ACV can slightly  Experts generally agree that most people, especially women and older adults,

Experts generally agree that most people, especially women and older adults,

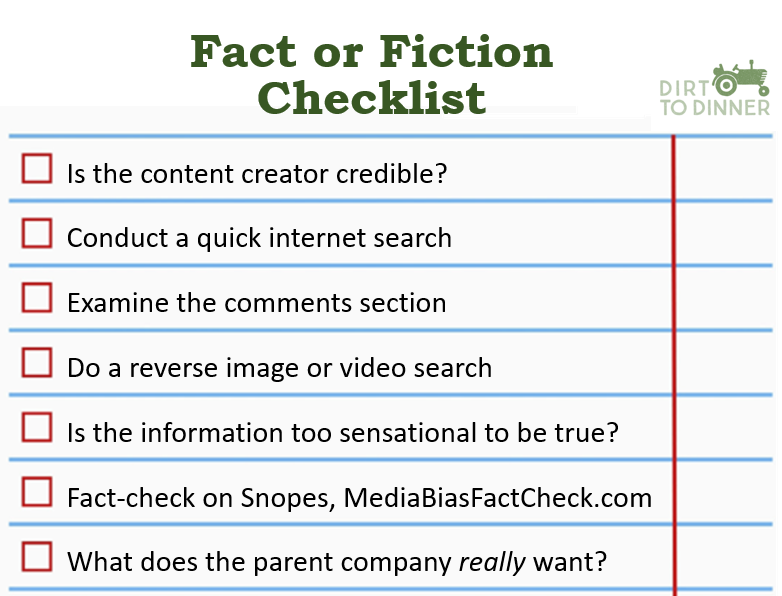

When it comes to understanding our food – especially things like health and nutrition – professional standing means a great deal. You trust scientists, educators, doctors, and healthcare professionals. Close behind, you once again value the opinion of people close to you, notably family and friends.

When it comes to understanding our food – especially things like health and nutrition – professional standing means a great deal. You trust scientists, educators, doctors, and healthcare professionals. Close behind, you once again value the opinion of people close to you, notably family and friends.