What is the Farm Bill?

The Farm Bill is the comprehensive federal legislation that lays out our food and agricultural policies. Think of it as a blueprint, or rules of the road, for guiding the production of the food consumers here and around the world depend upon.

The Farm Bill dates back to 1933, when in an effort to help farmers devastated during the Great Depression, Congress passed the Agricultural Adjustment Act, providing basic commodity supports. Farm legislation traditionally has been renewed every five to six years, expanding with each bill to cover an ever-wide range of national policy objectives.

What’s in it?

Think of the Farm Bill as a great big bus – with enough seats from everyone from the farm field to the dinner plate, from the American heartland to the most distant export market.

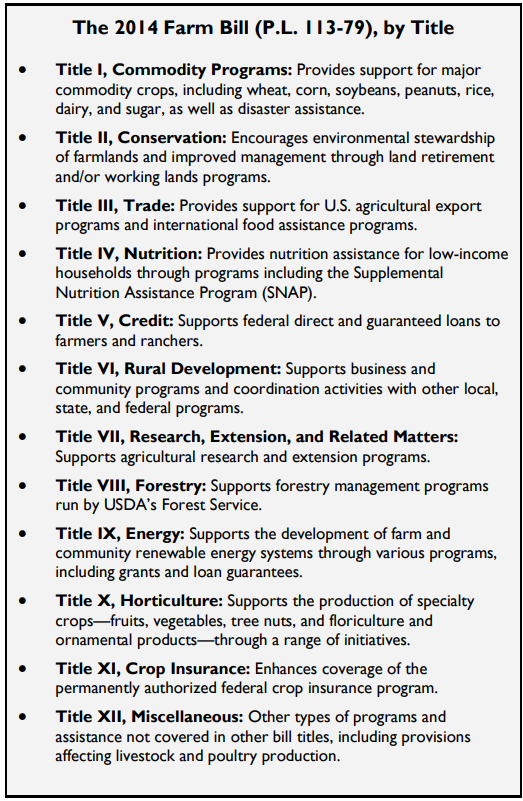

From its initial focus as an economic support plan for farmers, the Farm Bill has grown, pardon the expression, like a weed. The last farm bill, Agricultural Improvement Act of 2018, included 12 separate titles and ran over 800 pages.

From its humble origins, the Farm Bill now lays out a basic blueprint for commodity supports, crop insurance, farm credit, conservation programs, rural development, bioenergy, commodity market regulation, research and extension services, trade promotion, forestry, horticulture, food safety and nutrition – and more. The table of contents for the last Farm Bill ran 16 pages – longer than the average piece of legislation placed before Congress.

The sheer scope of the legislation makes it one of the most complex and daunting tasks facing Congress.

The number of voices that must be heard in drafting the legislation has grown in lockstep with the bill’s span of goals and objectives. And with each Farm Bill, the task of finding consensus grows more and more demanding. Differences on policies and especially spending priorities have led to simple year-long extensions of the 2018 law.

How much does it cost?

As the Farm Bill has grown in size, so has the price tag. The total five-year tab for the 2018 Farm Bill is estimated at about $428 billion dollars, according to the Congressional Budget Office during the last round of Farm Bill deliberations. That’s about $1,300 for every American over those 5 years, or roughly $260 per person per year.

That number again?

$428,000,000,000

As high as the numbers are, the five-year cost of the Farm Bill remains only 9 percent of the 2025 federal budget – and less than 2 percent of the federal budget on an annual basis.

In fact, it’s a pittance compared to federal spending. Social Security spending ran about $1.354 trillion in 2023. Healthcare clocked in at $889 billion, Medicare another $848 billion in that year. Our national defense budget hit $820 billion, with another $302 billion for veterans benefits. Even interest on the national debt ($658 Billion) topped the cost of the five-year Farm Bill. Still, nearly a half-trillion taxpayers dollars should garner some attention – and it has.

Where does the money go?

Now before anyone goes all ballistic over how rich this makes the American farmer, let’s take a look behind those numbers.

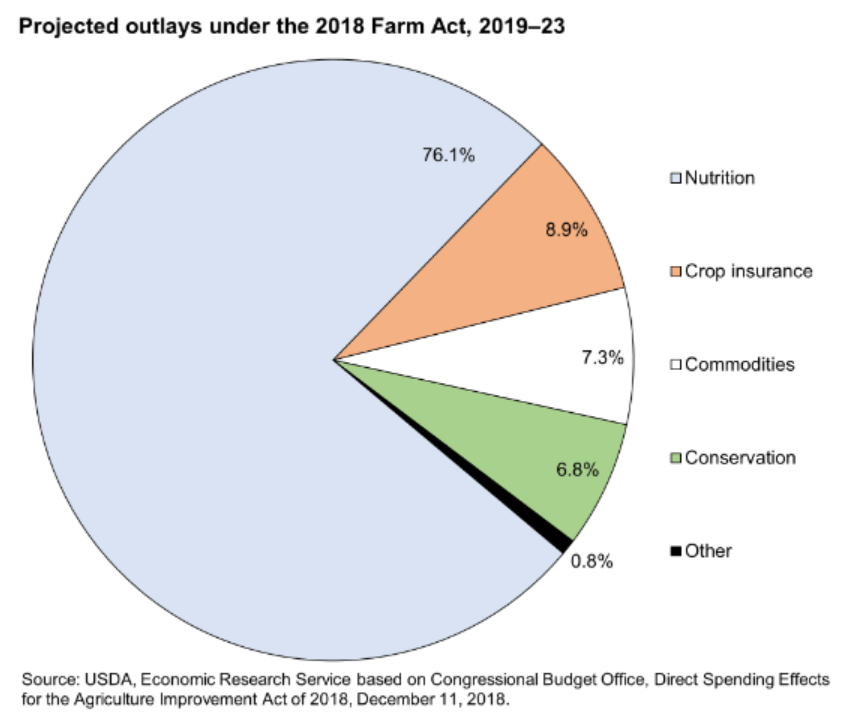

The latest data from the Economic Research Service at the U.S. Department of Agriculture notes that the overwhelming majority of spending comes through four specific areas (or titles) the bill.

Three are mainstream farmer-oriented program areas – commodity price supports, crop insurance and conservation. These three make up about 23 percent of the total Farm Bill tab.

Where does the rest go? All those other areas cited above – research, regulatory oversight, trade promotion and the like – make up about 1 percent of the bill.

The remaining 76 percent of spending goes to nutrition programs.

Yes, three-quarters of our Farm Bill spending is devoted to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as the Food Stamp Program), and programs such as the National School Lunch Program, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC), and others.

Yes, three-quarters of our Farm Bill spending is devoted to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as the Food Stamp Program), and programs such as the National School Lunch Program, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC), and others.

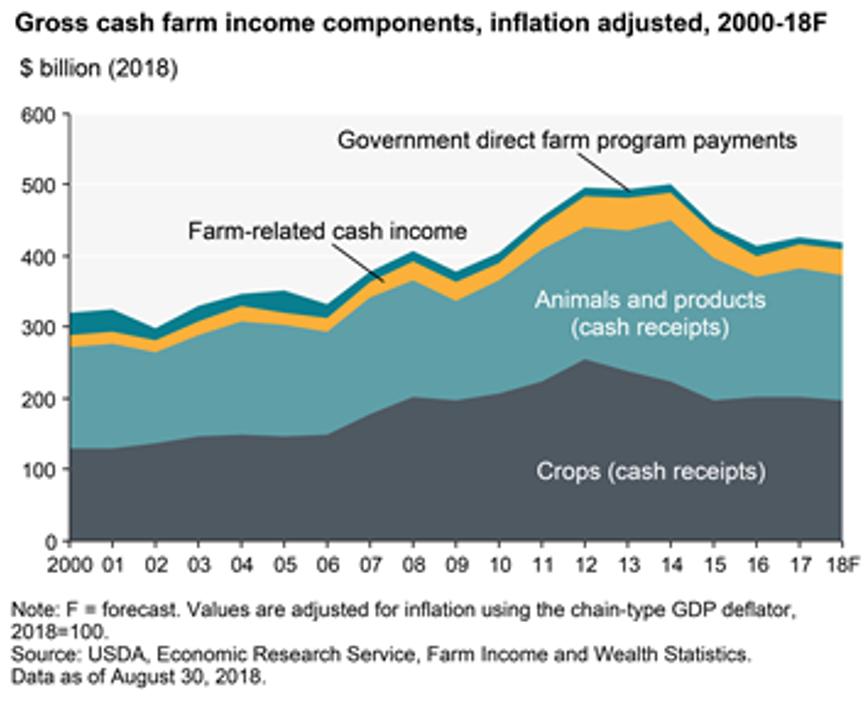

Programs authorized through what’s known as mandatory funding aren’t subject to the annual appropriations process in Congress. They are funded through the Commodity Credit Corporation and respond to market conditions and other economic considerations.

Discretionary funding covers programs with a price lid and require specific congressional action to exceed them through additional appropriations. The SNAP program is mandatory funding. As as more people sign on to the program, the costs automatically go up as well.

In other words, it’s very difficult – and maybe politically impossible — to shut off the spigot of taxpayer dollars.

What’s the math for consumers and taxpayers?

As we noted, the average American pays about $260 each year to cover the costs of the 2018 Farm Bill, according to figures from USDA, the CBO and other government sources. For a family of four, that is just over $1,000 per year.

If SNAP costs were eliminated from the calculation, those figures drop by almost $200, to roughly $60 per person per year. For the family of four, the cost would decrease to $210 per year, a reduction of $790.

If SNAP costs are kept in the Farm Bill, and the projected increases in costs prove true, the average per-person and family of four costs of the farm bill will increase beyond the $260 and $1,000 estimates.

So what’s the holdup on a new Farm Bill?

Congress has made a serious run at a new Farm Bill for more than two years, but with not quite getting over the finish line. The last Farm Bill technically expired during the national tumult surrounding the Covid outbreak, and the transition from a Democrat to Republican administration made agreement among legislators even more difficult. An extension and use of continuing resolutions added to congressional appropriations helped extend the bill.

But plain old politics also contributes to the impasse.

For some time, the rising costs of SNAP flew under the radar as federal spending on health care soared, and overall federal spending expanded at what many consider an alarming rate due to Covid and other factors. But a major debate is nonetheless present over the rising price tag for the Farm Bill, with the SNAP program the primary target for budget-conscious legislators. Questions about the likely need for some form of direct financial assistance for farmers due to the continuing global furor over tariffs and trade also are very much a part of the farm policy debate.

For some time, the rising costs of SNAP flew under the radar as federal spending on health care soared, and overall federal spending expanded at what many consider an alarming rate due to Covid and other factors. But a major debate is nonetheless present over the rising price tag for the Farm Bill, with the SNAP program the primary target for budget-conscious legislators. Questions about the likely need for some form of direct financial assistance for farmers due to the continuing global furor over tariffs and trade also are very much a part of the farm policy debate.

Critics of the SNAP program have floated the idea of separating the program from any new Farm Bill. Such a step would dramatically lower the price tag. But more experienced legislations say the nutrition and food assistance programs are in the bill for a very important reason.

Proponents of keeping SNAP within the bill point to the need to appeal to House and Senate legislators with largely urban and suburban constituents. Absent the link to SNAP, they warn, there is a risk of push-back from those inexperienced in the importance of solid food and farm policies.

Or to put it more bluntly, there is a risk of Democrats from blue states looking for leverage against Republicans from red states in the Midwest and south. It’s a high-stake game of poker, with the Farm Bill sitting in the center or the table.

In simple terms: don’t be entirely surprised if a new and better Farm Bill remains elusive in 2025.

What will the Farm Bill cost in the future?

The future price tag can’t be accurately estimated at this time, obviously. There simply are too many uncertainties about the decision to be made by a Congress made up of a high percentage of Farm Bill virgins – that is, legislators who have never before been through the process of crafting omnibus farm legislation. More than one-third of the U.S. Senate is made up of senators elected since the last Farm Bill was passed. In the House, the percentage is almost double – 67 percent.

After two years of frustrating delays in addressing the need for new farm and food legislation, Congressional and Administration leaders pledge their best efforts to see the Farm Bill through to completion in 2025.

The stakes are high.

Farmers need to know the rules of the road, and the policy directions that will shape their planting and marketing plans in an era of economic stress throughout the farm economy.

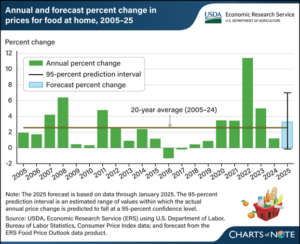

Consumers need to know that their food is available, safe, nutritious and affordable, which means some clarity in the way plans to reduce staff and funding in various food-related programs and agencies will play out.

Put the taxpayer on that list, too. Simply locking in the existing Farm Bill policies means the price tag for the Farm Bill will continue to escalate.

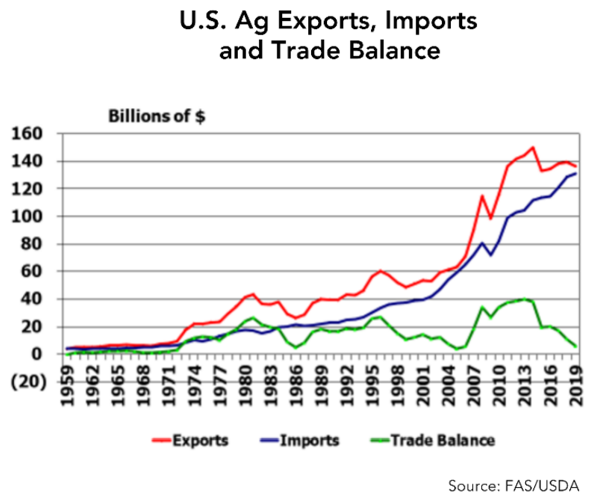

The world needs to know how reliable the United States can be as a supplier.

The cost of SNAP and comparable food-assistance programs administered by USDA already is estimated to rise to $110 billion in 2025 by the Congressional Budget Office.

The Congressional Research Service (CRS) estimated a 10-year continuation of existing law would cost $1.4 trillion, with the SNAP share of the tab rising to 81 percent. CRS pointed out that such spending would be an increase of about $600 million.

Mostly I look for sales. If it’s a good deal, that’s what we eat.

Mostly I look for sales. If it’s a good deal, that’s what we eat. What do you think? Of course they are going to keep going up. Nothing I can do about that.

What do you think? Of course they are going to keep going up. Nothing I can do about that.  We’ll go out on weekends now and then, but not during the week. And we try to leave the kids home when we do. That saves us a lot of money.

We’ll go out on weekends now and then, but not during the week. And we try to leave the kids home when we do. That saves us a lot of money.

We’re still without our long-overdue

We’re still without our long-overdue