Lucy Stitzer: Welcome to our Dirt to Dinner podcast with Aaron Wetzel, Vice President at John Deere with their Production and Precision Ag Production Systems. Growing up on a farm in Illinois, Aaron has over three decades of experience at John Deere. He is a seasoned leader and expert in the global ag industry, holding roles across sales, marketing, finance, and product development. Speaking with Aaron, I was so impressed with John Deere’s running journey from the self-scouring steel plow in 1837 to the John Deere tractors to the company’s evolution into a pure technology company serving their farmer customers. We welcome Aaron Wetzel.

Good morning, Aaron. Thank you so much for joining Dirt to Dinner and we are very excited to have you on our podcast. Why don’t you tell us a little bit about yourself and a little bit about your introduction to John Deere?

Aaron Wetzel: I have been fortunate to work for John Deere now 37 years. I always like to say I started when I was 10, but that’s not real. I started right in the middle of my college studies at Augustana College. I was studying accounting and became a summer student working at our corporate offices in Molen, Illinois. And that ultimately transferred into full-time employment.

On my graduation, upon working for Deere, I started in the accounting finance function. I quickly realized that accounting was not necessarily what I wanted to do. It was a great foundation to have, but I wanted to make the beans instead of count beans. And so I moved into the sales and marketing function and worked my way through the organization.

I’ve been fortunate in my career to work internationally. I lived and worked in Europe for a few years and also lived and worked in Latin America primarily in Brazil running our Brazil operations for several years from 2007 to 2012. I’ve worked in not only sales and marketing but in manufacturing and product development.

I’ve worked in our financial services business as a chief marketing officer for John Financial and today I lead our production and precision ag business. So really the culmination of coming together of our equipment and technologies and how we create value for customers. And so it’s as I look back as a farm kid from central Illinois never in my wildest dreams, what I have imagined, who have experienced what I’ve experienced and lived where I’ve lived, all as a result of my career at John Deere.

That’s a great story, a great career. And so tell me how John Deere has been running like a deer since 1845. So what values have kept you at John Deere and that have also kept John Deere going for over 180 years?

I would say first and foremost is our commitment to our customer. You know, I think that’s what has enabled Deere to exist for now nearly 200 years is through the thick and thin of agriculture in the good times and the bad times, Deere is there and working to support the customers that we serve, looking at the opportunities to help create value for them and we’ve been doing that over and over and reinventing ourselves as a company over that almost 200-year history.

I think another thing that’s important is our focus on commitment to quality and innovation. We’re continually bringing the latest in technologies to our customers and that started in even in the iron space with the self-scouring plow back in 1837 that started the whole company and we’ve been very much focused on how do we bring that innovation but it’s it’s steeped in us having a deep understanding of the customers that we serve.

As I’ve worked across the globe I also think our commitment to what we call all the how in doing things the right way has also enabled Deere to navigate through challenging times and make sure that we’re doing the things that are right for our customers and that’s what’s kept me at Deere and it’s been an amazing journey but at the end of the day what passions me to get out of bed every morning is what can we do to help create new value for customers and as a as a farm kid myself and making decisions as growing up in the mid-80s when it was a very challenging time in agriculture farming was not an option for me to be able to be in the industry and to be able to do what we do is really rewarding.

So creating value for the customer and that means helping them become more profitable, helping them with their labor and helping them be as sustainable as possible given the times really with the new technology starting as you said earlier with the plow, you know, changing the plow so instead of just going straight through it can dig up the earth a little bit better and make it easier for the farmer.

Were there some tough years. Were there lessons that you’ve learned that have carried you through to today?

Yeah, I would say, in agriculture is a series of really great times and a series of challenging times. And that’s been the interesting piece during my 37-year history is I’ve seen both. I’ve seen the really positive euphoric times, but I’ve also worked through some challenging times. And for our business, it’s again staying focused on what the customers need. How do we create new opportunities to deliver value for them?

I think about working in Brazil during the 2008 financial crisis and a significant change in credit availability caused a tremendous decrease in demand for products and we needed to get creative in how we manage our business, how we manage our inventories, but also keeping in mind what customers are going through. And so with with our financial services business. How did we step in and help them through a really challenging time by offering credit available to them?

That’s I think probably in the most critical times our John Financial, the financial services side of our business has been a real key partner in working with our customers, especially during times of hardship and being able to work specifically with customers in their specific needs and then arranging payment options that need their cash flow requirements to be able to navigate through a challenging time. And I think that’s what’s helped Deere navigate over nearly 200 years of history is that real close connection we’ve built with our customers.

I can imagine that the John Deere financial was a lifeline for customers, especially in 2008. So all of your inventions are helping the farmer become more productive as I said earlier, more profitable, more sustainable. And how did you end up just focusing on the customer? Did you make a conscious effort with your focus is completely on the customer and anything that you invest in to grow is all pertaining to the customer.

I mean it sounds so obvious and it sounds so clear but was there ever a time in your history where you veered off and you had different focus and you were focused on more on machinery or doing something different than your eye only on the customer?

Yeah, it’s been a very long journey of transformation for our company. Lucy, you said it well. You know, if I look back 25, 30 years ago, we were a very product focused company and machines, bigger, stronger, faster, wider machines to be able to maximize productivity for a person in the cab. And we optimized our business around each of those products, whether it’s a combine, a tractor, a planter, or a sprayer.

What’s been exciting over the past few years as we’ve really doubled down on our technology stack and reorganized our company around our customers. Like today, I’m responsible for the portfolio of opportunities to serve the large scale producers in our business. So, corn and soybean producers, sugarcane, small grains, and cotton producers globally. And so now we’re optimizing our business around what does the customer need?

And it’s that combination of the technology with the product to create that value. And that’s been a real exciting time for me to see that trans information take place, but it’s also helped our business accelerate some of our developments in the technology space to create that value for customers. And really, it’s bringing that technology to help us more precisely place seed, chemical, and nutrients in a time where customers are very much focused on their bottom lines and how do they optimize their inputs.

By doing that, a more precise placement, we’re seeing customers improve their yields because you’re doing the job better, doing the job of planting better, you’re doing the job of spraying better. And that’s continuing to propel our investments to say how do we create those values in those particular production systems that help those customers and help us. And so that transition of just being a singular product focus to now being a customer focus is aligning our investments. It’s aligning the organization our channel and really more deeply understanding the challenges our customers face every day in field.

And you’re really helping the customers make the world a better place, feed more people on existing land sustainably. That’s a higher purpose than just making machines. So before we go into the technology, can you just explain to our listeners a little bit about what kind of crops the farmers harvest? You know, corn, soybeans, cotton, but you also work with lettuce farmers? So what’s the broad range of farmers? And then you also are in construction and timber.

We also have a business focused on turf. So as I said earlier, we’ve we’ll separate our businesses kind of into three separate categories. We have our what we call our production and precision ag business which is what I’m responsible for in creating value for customers that produce corn and soybeans, small grains. So that would be wheat, canola, lentils primarily in Canada, Australia, the great plain states of the US, Europe, sugarcane producers primarily Brazil but also Australia and parts of Asia and some in United States. And then cotton, a fiber that is important for the clothes that we wear and produced in the US, Asia, but also in Brazil predominantly.

And so we’re creating a portfolio of products to help customers produce those crops and technologies to help them do it more sustainably and with better focus on their input. So that’s the production precision ag business. The small ag and turf business we call is really focused on dairy and livestock customers. So bailing, mowing, as well as high value crops. So that would be lettuce producers, orange producers, orchard and vineyards and we’re building out a suite of technologies that we can then leverage from our production and precision ag business into those segments to create the value for customers in a similar manner of more precisely placing chemicals and nutrients.

And in some instances it’s on our own machines, but also in a lot of instances it’s on non- Deere crops. And so being able to take advantage of the technology suite that we’ve got to create value for them were focused in that business. And then we have a turf business that’s a part of that which is commercial landscapers, homeowners, golf courses where we create a series of products that enable us to help create value for them and doing the job faster.

So, I worked in that business for a very long time in my career and on our consumer space, for example. I love having a very nice looking yard, but I don’t want to do it. So, I outsource it to a commercial landscaper that does it for me. And so, we create the machines to be able to do that for them. And then we have our construction and forestry business. So again, all the machines that are in place for earth moving.

You mentioned the timber. So our forestry business that helps harvest lumber around the globe to produce pulp and paper. And then we have a road building business through an acquisition called Verkett that gave us a leading position in building roads around the world.

So those I would say are the main business units of Deere today that encapsulate our global operations and then we have some supporting services like our aftermarket business so the part support that’s mission critical for our customers and then we have our financial services business that I mentioned so we really cover the gamut.

When people think of John Deere, you mostly think of farming but didn’t really realize that you were in the lawn and turf and really the timber business as well as road building.

And then in the center of all of that we have what we call our technology stack and that’s really the organization that builds and develops the leading technologies to create the value for customers that we then incorporate into each of these customer segments and product portfolios that I mentioned earlier.

Well, let’s move into technology and I think we can start with the See and Spray technology which is very exciting.

It’s an exciting technology. It’s one that we’ve been working on for quite some time. It’s really helping customers tremendously save on inputs with our technology. We’ve got a series of cameras systems computing on the machine itself. highspeed computing and machine learning capabilities that as a customer is going through the field at 15 miles an hour with their self-propelled sprayer.

We have the technology on the back of the sprayer that’s controlling the nozzle system on the boom that’s only spraying the weeds. And I’ll use the analogy I go back to being the kid that was 8 years old in a field in central Illinois and we used to walk beans. I don’t know if you walk beans, but we walk beans to kill the wheats. And I always had this dream that I said, “Why can’t we have like a laser beam that would just shoot down the field and only kill the weeds. So I don’t have to be out there walking beans as a kid.

And what’s exciting now nearly 50 years later is the technology exists and we have machines now traversing through fields only killing weeds and that is saving our customers nearly 60% chemicals and in today’s environment that is a significant portion of their P&L and that’s really helping them save money in a time where commodity prices are the challenging and that’s helping them improve their profitability especially at this period of time.

That also not only is it saving them money, it’s also more sustainable for the environment because we’re putting down less chemicals. And so it’s a win-win from being able to improve profits, but also the environmental impact is very positive. And we’re doing that through incorporating these leading technologies into our machines ultimately to create this value for customers.

So does the customer have to program for its specific crop or does the machine just know exactly, okay, this is soy, this is corn, this is what it is, this is how much distances between the rows and knows exactly what to do?

Yeah, it knows. So, we’re spending an enormous amount of time and energy and investment to train the models. As we said, it’s got a machine learning model. So, it’s we’ve taking these machines across thousands and thousands of acres to educate the model on what’s a weed, what’s a soybean, we train it into different crops and then once we feel confident on where that particular performance is then we will make it available to customers.

And so right now we’re in soybeans and cotton and we intend to expand that across all of the crop segments that customers produce. And so it takes some time to get the machine learning capabilities in place, but as it gets faster as we continue to develop into each crop because we learn from one to apply it to the next. And so that’s what’s super exciting about the technology.

It’s the pace of with which it improves and the ability for us to then take that not only to different crops but we take it to different geographies. Crops grown in central Illinois or Iowa slightly different than what we see growing in Brazil. So we need to train the capabilities for those particular applications in that and we’re doing that as well. So we intend to take this capability not only across crops but across the world in terms of offering to customers

Is there something or someone on the tractor monitoring them, making sure that they don’t veer and go astray?

Yeah, so these are it’s designed for a self-propelled sprayer. So, it’s a dedicated machine form that does spraying. You still need to have a person in the cab that’s operating the product, but we have other technologies that are enabling customers to do things in an autonomous way.

And that’s another key pillar of our strategy going forward from a technology perspective to help address some of the challenges customer face and that’s tough.

We’ll talk about the automation in a little bit. When you’re spraying, one question one would have is: is there drift a little bit over to the crop so the crop has to be Roundup Ready or it has to have that, as well?

So there are there are special nozzles that we have that help reduce drift. Drift is a concern for many customers. We have a pulse width modulation system on our sprayers that increase the droplet size so that it reduces the drift and we’ve launched that technology probably about 10 years ago that is now widely used by our customers and it really addresses that concern you just had around drift because there are some chemicals that are very concerning for customers in terms of drift.

Let’s say you’re spraying Roundup Ready soybeans and you’ve got a corn field next to you. You got to make sure that reduce that drift otherwise you’ll have a negative impact. So our technologies and our products are positioned for customers to be able to do that to the best of their ability.

And then how about nutrients? Does the same machine do nutrients as well?

Nope. We will be able to do nitrogen and you can do a myriad of other opportunities but those are still in development but today it’s really focused on glyphosate and other weed management chemicals.

So you were talking about when you were younger and you were walking through soy and you were spraying the weeds and you thought well wouldn’t it be great if there was a laser that would get rid of weeds. There are some tractors out there that have robotic weed pullers and I don’t know have if the laser is available but is that something you’re moving towards is eliminating the weeds without any spray?

We see those opportunities. A lot of startup companies today that are looking at mechanical weeding solutions. A lot of those are primarily focused in the European markets. We have not specifically targeted any investments in that space primarily because the productivity of those machines for the customers that we want to serve in our primary markets like the US and Brazil and corn and soybean producers whereas the main lead investment areas for our technologies.

It’s really not hitting the productivity levels that those customers are looking for. So, we’ve really started, we’ve really stayed focused on the CN spray and the machine learning and the cameras and the computing capabilities that deliver on that productivity that those customers are looking for.

So, now let’s move on to automation. I was at a conference somewhere and someone was on their phone and he’s like, “Yeah, I’m farming my field.” And I was like, “Wow, that’s interesting.” So, he was on his phone and could program his tractor. So that’s what you see as the future is farmers can stay home and have a nice dinner and their tractors will just be moving through the fields 24/7?

Yeah, it is definitely a vision we have for our future and what customers are able to do. You know, if we think about our customers we serve today, labor is becoming a greater challenge for them. Finding qualified labor to do the work and because of that we’ve really made some investments in automation of jobs so that you can put less qualified workers in the cab, but also in fully autonomous solutions.

And that’s what’s exciting is to see where we’re going with this technology opportunity to really create a whole new opportunity of value for customers. And that’s getting the operator out of the cab over the long haul. Not only are we doing that in our large ag customer space, we’re doing it across the portfolio.

And I don’t know if you saw the most recent consumer electronic show that we participate in where we showcased our focus on autonomous solutions not only for our large ag producers but for orchard and vineyards and for our construction customers. And what the unique opportunity Deere has is we have this centralized tech stack that is developing the capabilities and then we take that and leverage it into the various customer applications.

And so there we had the same technology opportunity move from large ag producer We had the same camera systems and computing capabilities on a small zero turn mower for a commercial landscaper. We had that same technology stacked into an orchard and vineyard application for customers to blast spray or mow through the vineyards and orchards.

And then we had an example of that same technology being applied to earth marine business with dump trucks being autonomously maneuvered through a job site. And so that’s the power I think of what Deere is able to provide is making some investments around one customer segment but then leveraging that across many and creating a whole new stream of value for them.

That’s incredible. So you have the same technology for a lawn mower that you do for a huge combine and then for cutting down trees. And how is that programmed and how do you teach the machine what to look out for or what not to run into where to go? And you’re using satellite imagery or using Blue River technology?

So, we’re using an acquisition that we made back in 2017, Blue River. It is a machine learning capability that combined with the camera system that we’re developing to place on each of the machines, those images that are being captured, we’re really looking at what’s in front and around the machine. And if we see people or animals, we stop and then determine if the area is now free and then allow the machine to proceed forward. And again, like I talked about in the CNS spray opportunity where we’re educating the algorithms to discern what is weed and what is crop in all of the various crops.

We’re doing the same thing from an autonomy perspective to learn more about what do obstacles look like in a corn field, what do obstacles look like on a golf course, what do obstacles look like on a job site. So that we educate that to understand when those obstacles arise, stop the machine. and then allow it to clear and then allow it to be. And so that’s really the work that we’re doing, not too dissimilar from what automotive industry is doing.

And I think what’s unique is we’re sharing a lot of the same challenges automotive has, but we’re also having additional complexity because we’re doing jobs. We’re not just moving people from point A to point B. We’re out tilling the soil. We’re planting the seed. We’re spraying the crop. We’re mowing the turf. So we’ve got to also ensure that the job is being done to the level of satisfaction that the customer expects and that’s an additional complexity we have in this whole new autonomous world.

I think that’s just absolutely incredible and I think you’re way more advanced than automated driving because driving you have all these nuances. What does the stop sign look like? What if the stop sign is bent…is it still a stop sign? You have to put so many other inputs into the driving aspect, but you still have a lot of inputs on the farmer.

The difference between a farm and my backyard and the golf course – there’s just a huge variety. So, the technology, did you have to buy or acquire or hire a lot of programmers to do this? I mean, how did you come about just going from making a machine, thinking about a great engine to now programming the machine to do everything that one can do without someone sitting in the cab?

It’s been a journey building the technology capabilities I would say over 20 plus years. It started with initial investment we made in a company called NavCom in 1999 that gave us the global positioning capabilities to drive really basic what we call autotrack and that was just driving the machine straight through the field and reducing the overlap of the implements that increase productivity and then we fast forward to today or in the near term where we talked about the Blue River acquisition in 2017 that gave us machine learning capabilities.

In 2019, we bought a company called Bear Flag that also was working in the autonomy space and in 2020 we purchased a company called Harvest Profit that helps customers identify really their P&L income statements for their operations and that those are some of the basic tenants of elements of our technology stack in addition to our own development opportunities of us going out and hire ing software engineers to do the work of embedding a lot of the electronic capabilities into the machines.

Building the capability of getting the data from the field into the cloud and then a team of folks to help us analyze the data and help support customers in decisioning and managing their operations from their phone. And like you mentioned at the very beginning of this question, I’ve been in numerous conferences where the customer I’m talking to will show up with his phone. He’ll say, I’ve got my operations going on. And they’ll open up their operation center and they’ll show me where their tractors are and their combines and what they’re doing. And it’s changing the game for many of our producers that they don’t need to be in the farm every single day. They can do it remotely.

And so it’s really freeing up their time to do other things that are more productive for them or more value added for them. But it ensures that the job is still getting done. We’ve really, I would say, been on a very long-term journey that we’re accelerating here. within the past five or six years but and we’ll continue to accelerate that as we see more and more opportunities for customers.

So what are you going to do with artificial intelligence and how are you going to utilize that going forward? I mean you certainly are using it to an extent right now for machine learning and trying to program the machines for today. But what do you do with all the data and how do you do any predictive analysis or where are you taking that?

AI is relatively new and I think companies are trying to figure out exactly how to make the best use of it and what questions to ask and again how to do predictive analysis. We are at the forefront of our artificial intelligence. You know the key opportunities that we see right now is how do we help do the job better.

You know the See & Spray capabilities, the autonomy capabilities, other automation of job steps is another application for us to take advantage of. You know you mentioned about the customer’s data. We’ve been very firm in saying that the data that that we’re collecting is the customer’s data and so they choose who they want to share that data with and we enable that sharing of data to happen but it’s all at the decision of the customers.

where does AI go in agriculture? I think we’re still trying to figure that out. We have an enormous amount of data and insights and so how do we help customers at the end of the day make better decisions in their operations? How do they better optimize their machine performance? We have an enormous amount of data just on the machines themselves. in terms of regular maintenance engagement with their dealer.

We have data around the execution of the job and ultimately the yields that come out of all of those job steps during the course of a growing season. And so we’re starting to work with customers to say what are you looking for in your future? What are the problems that you’re facing? And how can we work with you with the data to help solve those problems? And I would say we’re at the infancy of that right now, but it’s definitely going to be impactful for customers. And it first starts with building a robust data set that I think we’re uniquely positioned to have to be able to then create those insights for the long term.

I would think it would be helpful when it comes to variant weather patterns, flooding, droughts, you could reprogram or you’d have to reprogram your machine to adhere to very wet circumstances but still get the same yield that you would want to get for just a regular year.

Yeah, it’s interesting. We just were at a recent farm show and using the data in a macro level, we’ve actually been able to help educate customers that if you plant soybeans earlier, it actually has a positive impact on yield and by 5%. And so, and that’s meaningful for producers, especially in today’s environment, that just the day or the planting window that you start has a meaningful impact on what your actual yield outcome is.

And we’ve done that based on us looking at the data to say, “Hey, there’s an opportunity here, customer, for you do something different. And that’s one example of how we’re using data to help customers do the job better.

Or if it’s a very wet spring and it’s planting season, maybe you would reconfigure the tractor to plant differently. So, why would a farmer choose John Deere over your competitors? You’ve given us all sorts of advantages, but your competition must be doing some of the same things that you’re doing.

That’s a great question, and I have a great deal of respect for the competitors that we compete with in our industry. You know, we’re all out trying to serve our customers, but I think why the customers choose Deere and I think it’s really a combination of several factors.

One, it’s the quality and the performance of our products that are in the field day in day out. It’s the technology that we have incorporated into those machines. It’s the seamless flow of data into the John Deere operations center that helps them manage their operations more efficiently and effectively. And I think the final piece is really around our dealers and the dealer network that we’ve established around the world is I believe second to none in terms of how we support our customers in the field.

And at the end of the day, we can have all the great technology and we can do all great things, but the machine has got to work in the field. And that’s what our dealers do every day is ensure that the customers have the product and the technology they need to do the job. And they’re there if something happens, they reduce the downtime and ensure that customers are up and running, especially during critical times during the course of the year, planting, harvest, spraying, and customers rely on those dealers. They’re one of their trusted advisers.

So, I think that combination of product, technology, and channel really differentiates Deere in the markets that we serve, and that’s what helps us garner the support from customers, and I’m very thankful for the customers that do business with us.

Is there any question that I didn’t ask you that you would like to answer or leave our listeners with any other key insights?

You know, I say deer’s been around for nearly 200 years. We want to be around for at least another 200 years and we’re going to do that by staying maniacally focused on the customers and how do we continue to reinvent ourselves year-over-year to understand the challenges that customers face.

We’re committed to make the investments necessary to create that value for them. We want to continue to be their trusted partner on this journey of helping them create the value in their operations. We want to do that through the products that we create, the technologies, and the combination of those together supported by our channel that at the end of the day gives them the confidence they need to do out and do the job.

And especially in challenging times, we’re there for them to help them be more productive and more sustainable for the future. And at the end of the day, we got a growing population to feed and we want we are excited to be a part of that and more importantly to partner with our customers to make that happen.

Well, thank you very much, Aaron, for making the world a better place through our farmers and through sustainability and having everyone have a better yield and enable us to feed a growing population on existing land. We won’t need to put more land under plow because of John Deere.

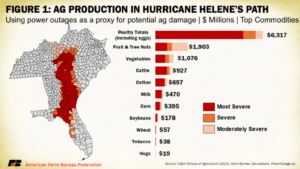

My part of North Carolina was hit especially hard, with epic flooding and devastation that simply wiped away many of the small towns here and left cities like Asheville reeling from destruction almost beyond description. The photo on the right shows Helene’s impact on my hometown.

My part of North Carolina was hit especially hard, with epic flooding and devastation that simply wiped away many of the small towns here and left cities like Asheville reeling from destruction almost beyond description. The photo on the right shows Helene’s impact on my hometown.

The U.S. Labor Department’s

The U.S. Labor Department’s

Russell and Brandy work hard to make a go of it in the demanding world of cattle production. It’s hard work keeping tabs on the cattle 24/7, protecting them from predators, and doing it all in a way that preserves the delicate balance that protects the natural resources they and their predecessors have relied upon for more than a century. It’s a rugged life made even more so by dealing with desperate immigrants passing through.

Russell and Brandy work hard to make a go of it in the demanding world of cattle production. It’s hard work keeping tabs on the cattle 24/7, protecting them from predators, and doing it all in a way that preserves the delicate balance that protects the natural resources they and their predecessors have relied upon for more than a century. It’s a rugged life made even more so by dealing with desperate immigrants passing through.