When the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) last month reported food price inflation of only 3.7 percent, few seemed to notice. That figure is almost double the food inflation rate since the early 1990s but still way below the numbers posted following the COVID-19 pandemic and the enormous disruption to the food system that followed.

As the Washington Post observed, “Overall, inflation is trending in the right direction.”

In the Covid era, food manufacturers and retailers had a single over-riding priority: Do whatever it takes to keep the pipeline of food as full as possible. Find whatever supplies of the food products consumers wanted and expected of the most modern and efficient food system in human history. Pay whatever needed to be paid to secure those products and see them delivered. Maintaining supply became the universal mantra.

Without a doubt, our food system did a magnificent job of rising to the challenges posed by the Covid era – and the demands of the public. Spot shortages and supply disruptions captured a lot of attention, but by and large, they remained the exception far more than the rule and an inconvenience more than a threat to consumer well-being.

A Sign of the Times

But rising to the challenge came with a cost: food inflation at record or near-record levels. Consumers seemed more than willing to ante up for the food we all want – at least for a while. We’re now seeing early signs that willingness to pay more and more for our food is giving way to a new consumer attitude – one of cost-consciousness that is leading more and more food manufacturers and retailers to shift gears.

Consumers are showing increasing resistance to inexorable food price increases. More and more of us are turning to store brands… price shopping across suppliers… taking more advantage of sales and promotions… simply choosing to look at less-expensive meal alternatives…and more. Some disgruntled food shoppers have even resorted to – gasp – doing without.

In simple terms, price has become an increasingly important consideration for consumers.

A May 2022 study by Ernst & Young found that nearly three of every five consumers say price is their foremost purchase consideration. Two of three consumers say it will become the most critical consideration in the next three years.

The food sector seems to have taken this shift in attitude to heart. They are asking hard questions of suppliers, seeking to bring more pricing discipline to all aspects of their operations. Food manufacturers and retailers report spending more and more time examining opportunities for cost-reducing innovations and making smart investments in new technologies that enhance productivity.

But the single factor of unpredictability most often cited in Dirt to Dinner: the human element. And the portion of our food system most vulnerable to this unpredictability: transportation, and in particular, the trucking industry.

Trucking’s Consequential Labor Issues

Managers and operators across the food chain have reported a widespread lack of the people needed to do many of the fundamental manual tasks demanded by the entire food chain. Work crews are needed to do the hard, often back-breaking work of harvesting and initial transportation of commodities and food products. Farm managers complain bitterly of a lack of willing workers to do the daily arduous tasks that come with daily farm and ranch life, especially in dairy. Even farm-service suppliers report shortages of mechanics, service technicians, and others vital to maintaining routine farm and ranch operations.

No labor shortage provides greater cause for concern than the trucking sector.

No labor shortage provides greater cause for concern than the trucking sector.

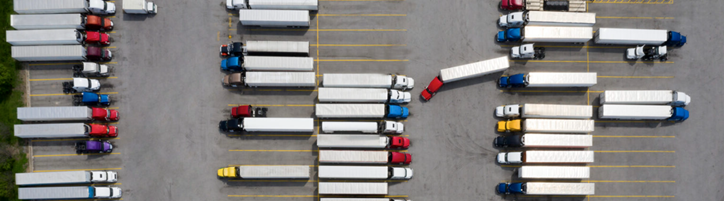

The statistics can be mind-numbing. According to the American Trucking Association (ATA), trucks move about 73 percent – yes, almost three-quarters – of the nation’s freight. That’s about 11.5 billion tons. Nearly 14 million trucks are on the road today, traveling over 327 billion miles.

The U.S. Department of Transportation reports over 750,000 active U.S. carriers. More than 95 percent of those operate ten or fewer trucks. The industry employs 8.4 million individuals as drivers or in support roles, with about 1.4 million actual drivers.

As impressive as the trucking industry statistics may be, they don’t explain the cause for concern from the food industry.

Trucks provide the common element across the entire food chain, providing the connective glue that brings food from dirt to dinner. Trucks bring farm inputs, transport commodities, animals, and ingredients from farm to collection points to food plants and production facilities. They carry finished food products to distributors and retailers and increasingly, to home delivery. A half-dozen trucks – or more – may be involved in the journey from dirt to dinner. When trucking services fail at any link in the chain, the likely result is system disruption – and supply interruption, and higher costs.

During the Covid pandemic, reports of a shortage of truck drivers were common. Food industry and transportation experts contacted by Dirt to Dinner report common problems with securing reliable truck services and cite this uncertainty as a significant factor behind the food sector’s efforts to secure contractual commitments from larger, proven, reliable suppliers.

Managers at large food companies report delays in service delivery and the growing issue of simple communications. “More and more of the drivers simply don’t speak English,” as one logistic manager explained. “You can imagine the problems that can create.”

Driver Shortage…or Driver Retention?

Those comments point to the debate within transportation circles about the existence of a “driver shortage.” Some prefer to call it a “driver retention” problem.

According to this point of view, the real problem is the simple unwillingness of people to accept the harsh demands of the profession. Extended periods of time away from home, constant travel, unfamiliar food, long spells of downtime, and boredom in strange locales have proven unattractive to prospective truckers. Even those anxious to find work and attracted to the ‘open road and personal freedom’ of trucking seem to become disillusioned and move on to work that offers something closer to the quality of life they seek – time at home, with family and friends, especially.

The industry has no choice but to adapt to these changing worker expectations, according to trucking industry figures. It begins with economics – meaning more pay. BLS reports an 2020 average truck driver salary of $48,710, rising to $49,920 in May 2022.

The agency agrees with food industry executives that demand for professional heavy and tractor-trailer drives will continue to grow, at a projected 4 percent per year through 2032. That works out to roughly 241,000 openings per year.

Observers of the trucking industry acknowledge the aggressive and creative efforts of the industry to improve driver conditions and adapt to changing expectations of potential drivers. They also note the special effort being made to attract more women to the profession – and more married driver teams.

But they also emphasize the need to move quickly – or see the recovery of our overall economy (and our food sector) sputter.