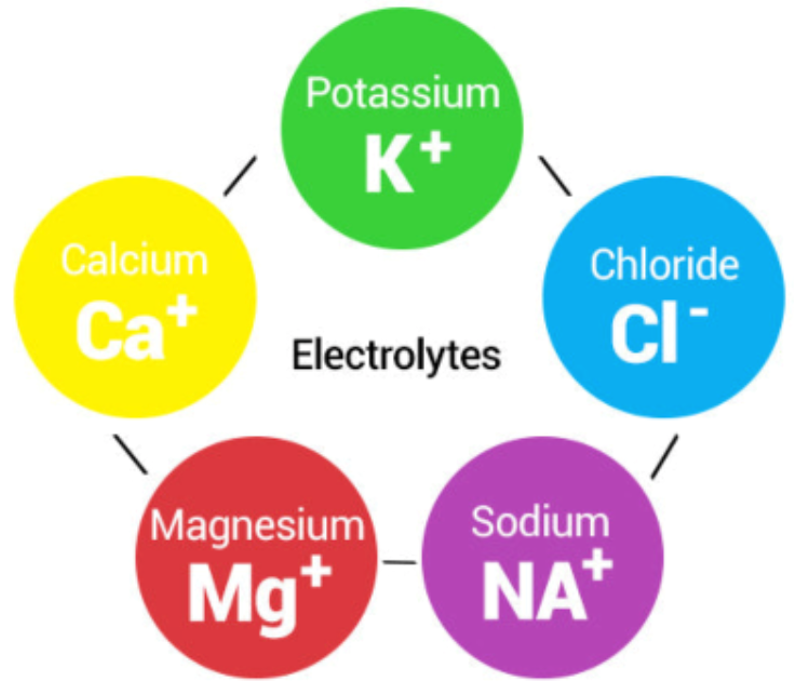

Electrolytes are minerals—like sodium, potassium, magnesium, calcium, chloride, and phosphate—that carry an electric charge when dissolved in bodily fluids.

These charged particles are critical to maintaining fluid balance, enabling nerve signals, and powering muscle contractions, including the heart itself.

Why We Need Electrolytes

Think of electrolytes as traffic signals for your body’s communication network. Without enough signals, nerve impulses stall, muscles falter, and blood flow gets stuck—leading to dehydration despite drinking plenty of fluids.

“Electrolytes are absolutely essential for normal function of nerves and muscles,” says Dr. Lawrence Armstrong, professor emeritus of physiology at the University of Connecticut. “Without them, we simply couldn’t move, think, or keep our hearts beating.”

The American College of Sports Medicine, echoed by experts like dietitian Holley Samuel, RD, sums it up: losing sweat means losing sodium and other minerals. If you only drink plain water, it doesn’t absorb well—your body drains it quickly, making you dehydrated all over again.

However, for most everyday activities, our balanced diets supply enough electrolytes: bananas for potassium, dairy or leafy greens for calcium, nuts and seeds for magnesium, salty foods for sodium.

“For the vast majority of people, water and a balanced diet are more than adequate to maintain electrolyte balance,” says Dr. Benjamin Levine, professor of medicine and cardiology at UT Southwestern. “Sports drinks are heavily marketed but often unnecessary outside of prolonged, intense exercise.”

In short, electrolytes are essential, but sports drinks and powders are often unnecessary unless your body is working really hard or sweating profusely.

How Much Do We Actually Need?

Let’s get specific. For general health, the standard Dietary Reference Intakes recommends:

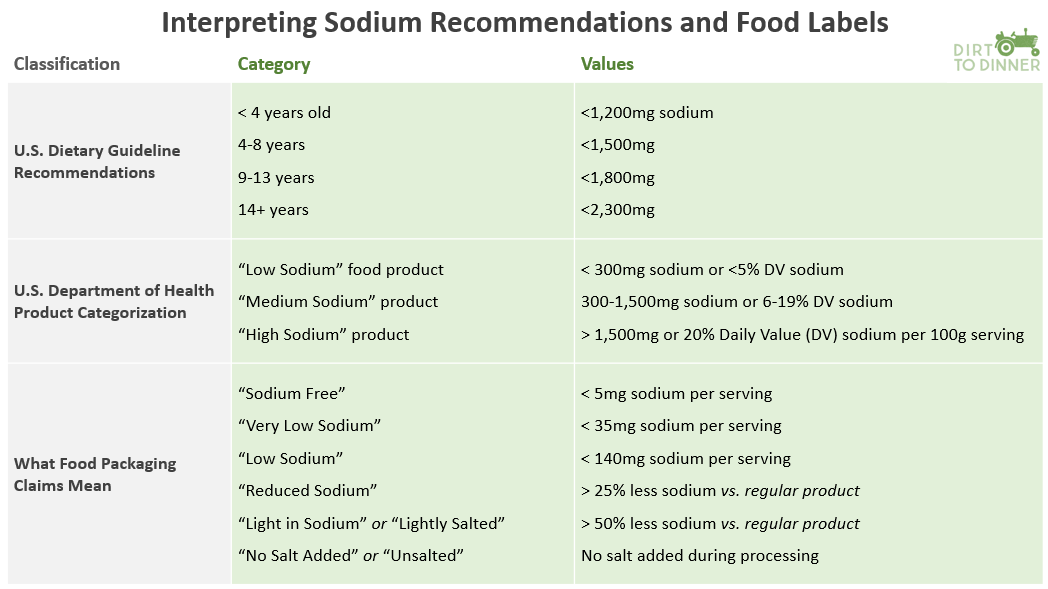

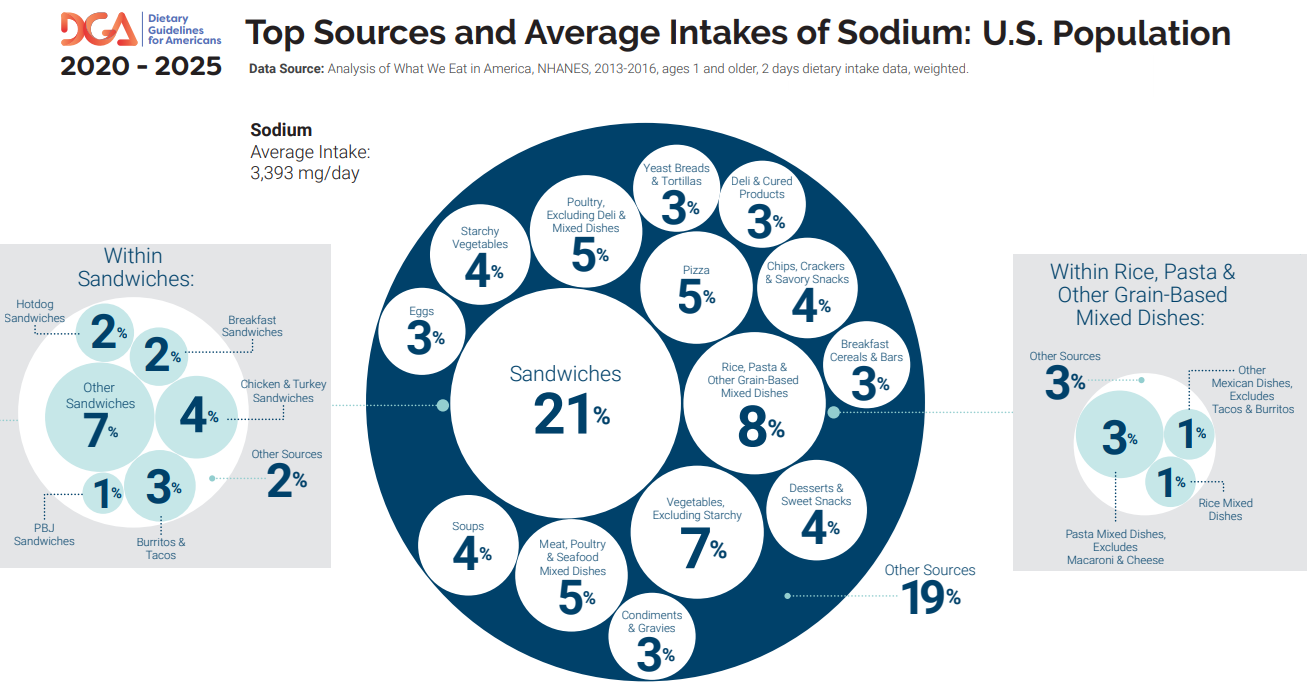

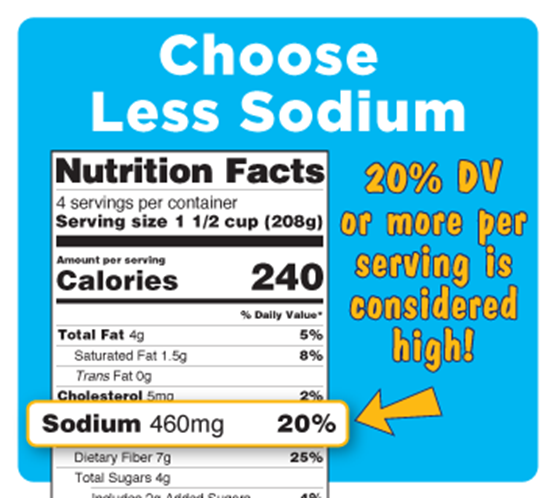

- Sodium: Up to 2,300 mg per day (but average diets often exceed this)

- Careful with sodium! 2 slices of pepperoni pizza = ~2,300 mg

- Potassium: ~2,600–3,400 mg daily

- 1 banana + 1 baked potato + 1 cup spinach = ~2,200 mg

- Calcium: ~1,000 mg daily

- 1 cup milk + 1 yogurt + 1 oz cheese = ~800 mg

- Magnesium: 310–420 mg per day

- 1 oz almonds + 1 cup beans + 1 cup spinach = ~350–400 mg

For athletes, needs differ. One study notes pre-training hydration should include ~500–600 mL of water or sports beverage 2–3 hours before activity, plus another ~200–300 mL shortly before. During exercise, aim to limit body weight loss to under 2% by matching fluid (and electrolyte) losses.

In endurance sports, sodium loss can skyrocket with intensity.

For example, experts note sodium loss increased by 150% as intensity ramped up in a 2019 cycling study. Sports dietitian Kala Reister recommends 300–600 mg of sodium per hour for intense, hot, or prolonged workouts.

Particularly in hot or prolonged events, these athletes benefit from electrolyte-carbohydrate mixes. A review of hydration science underscores the dual risk of dehydration and overhydration during long-duration workouts—and the pivotal role of fluids with electrolytes.

Personalization is key, too. “Athletes vary dramatically in how much sodium they lose, anywhere from 200 milligrams to over 1,000 milligrams per liter of sweat,” explains Dr. Douglas Casa, CEO of the Korey Stringer Institute at UConn. “That’s why personalized hydration plans are so critical.”

A randomized trial found that hydration plans tailored to sweat rate and sodium loss improved anaerobic performance, cognitive focus, and heart rate recovery—compared to ad lib hydration.

Maltodextrin: The Carby Sidekick

Maltodextrin is a starch-derived carbohydrate, easily dissolved and rapidly converted to glucose, earning a place in everything from baked goods to energy gels. It has a high glycemic index—meaning it spikes blood sugar quickly.

In sports drinks, maltodextrin provides an energy boost. This quick source of fuel is particularly useful in endurance contexts. Maltodextrin also helps improve hydration. In carbohydrate–electrolyte solutions (like Gatorade), maltodextrin enhances water absorption in the gut.

Think of maltodextrin as the “courier” in a postal system—it helps deliver water and electrolytes from your digestive tract into your bloodstream, just like a driver delivering packages to your house. Without the courier, deliveries (hydration) happen, but slower and less reliably.

A study of maltodextrin–fructose beverages showed improved exogenous carbohydrate oxidation and fluid delivery during sustained moderate-intensity exercise, suggesting better fuel and fluid absorption compared to other options.

“Carbohydrate–electrolyte drinks, especially those with maltodextrin, can improve fluid absorption and endurance performance,” notes Dr. Asker Jeukendrup, a leading researcher on sports nutrition. “But they are tools for athletes, not everyday consumers.”

It is important to note that outside of immediate athletic use, maltodextrin is processed by the body just like sugar. It doesn’t always show up under “sugars” on a nutrition label, but it still acts like one in your bloodstream—causing sharp glucose spikes. For those not actively burning through energy (such as endurance athletes mid-race), frequent consumption can contribute to the same metabolic concerns as eating sugary foods.

Marketing vs. Reality—What Consumers Should Know

Electrolyte products have flooded the market with packets promising “instant hydration,” bottles touting exotic mineral blends, “hangover cures,” and more. A SELF article reminds us: electrolyte drinks help rehydrate faster than water alone, but overuse can lead to fluid retention or high blood pressure.

Nor are electrolyte supplements a cure-all. Stanford researchers found they didn’t prevent illness in endurance runners—especially in hot weather—highlighting that factors like overhydration and long training loads were more relevant. And the British Medical Journal emphasizes that non-elite athletes often don’t need sports drinks—and that overconsumption may even be harmful due to sugar and electrolyte excess.

“Overuse of electrolyte supplements can lead to imbalances just as much as underuse,” warns Dr. Tamara Hew-Butler, associate professor of exercise science at Oakland University. “Hyponatremia—dangerously low sodium—can actually result from drinking too much fluid, even if it contains electrolytes.”

Electrolyte supplements are popular even beyond athletics, but most people meet needs via food and water; supplements help in intense activity or fluid loss scenarios—but excess can be harmful, especially for salt-sensitive individuals.

Practical Takeaways for Readers

- Casual exercise, daily hydration: Water plus a balanced diet is enough.

- Long, intense, or hot workouts (>1–2 hrs): Use an electrolyte–carbohydrate drink—or at least ingest something with sodium and drink some water. A good starting point is 300–600 mg sodium per hour.

- Illness with vomiting/diarrhea: Rehydration solutions (like Pedialyte or maltodextrin–electrolyte mixes) are appropriate.

- Personalized hydration: Measure your sweat rate and sodium loss to tailor fluids to your body’s needs. Sweating through multiple shirts? Dripping at the end of a cardio workout—this may translate into excess water loss and thus a need for higher electrolyte intake.

- Risks or restrictions: If you have hypertension, kidney issues, or dietary sodium restrictions, consult a healthcare provider before adding electrolyte products.

Electrolytes are non-negotiable for nerve, muscle, and fluid balance, but for most people, everyday diets provide all that’s needed for regular hydration. Supplements and sports drinks can be helpful in specific situations—such as for endurance athletes, excessive sweating, body fluid loss, or during intense activity in hot climates—but they are rarely necessary otherwise.

Research consistently shows that personalized hydration plans, tailored to individual sweat rate and sodium loss, work better than one-size-fits-all guidelines. And while electrolytes are essential, more isn’t always better: overconsumption of sports drinks adds excess sugar and may harm cardiometabolic health.

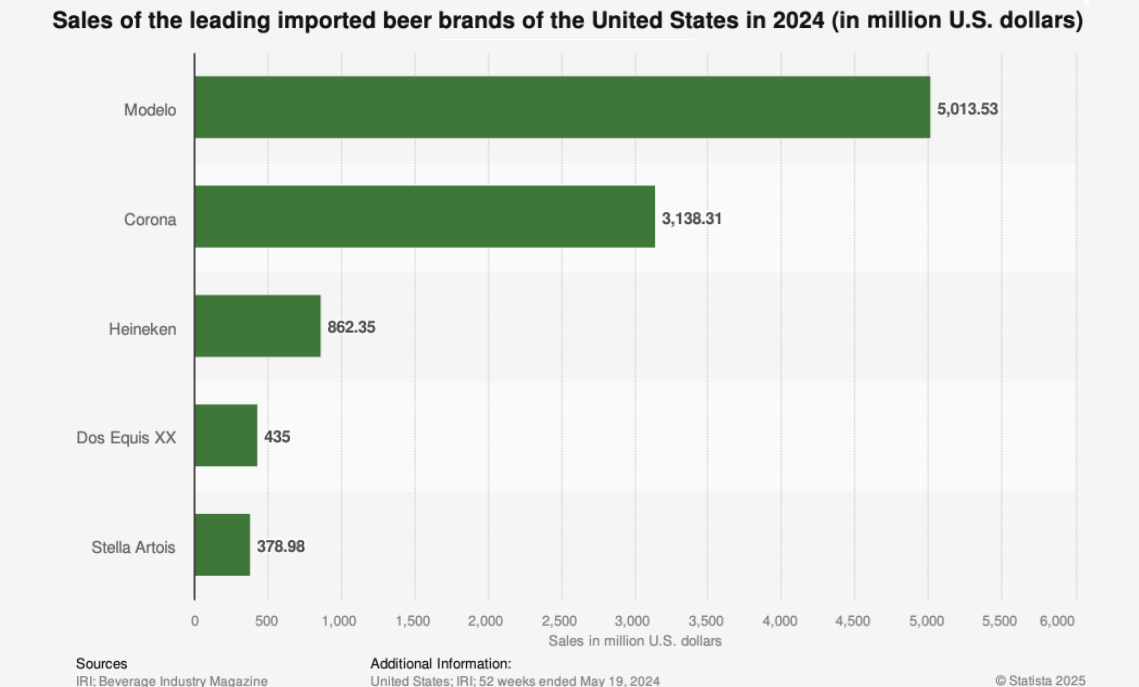

Perhaps of surprise to many consumers, tariffs on imports of aluminum play an important role in the potential price run-up for beer drinkers and other consumers.

Perhaps of surprise to many consumers, tariffs on imports of aluminum play an important role in the potential price run-up for beer drinkers and other consumers. Two of the most significant suppliers of imported beer – Canada, and even more so Mexico – enjoy a special exemption from the brunt of the tariff costs because of pre-existing trade agreements with the United States.

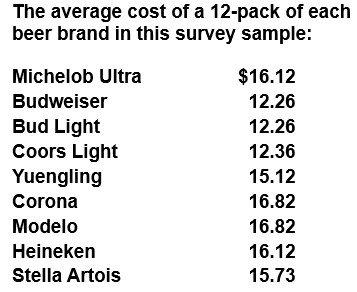

Two of the most significant suppliers of imported beer – Canada, and even more so Mexico – enjoy a special exemption from the brunt of the tariff costs because of pre-existing trade agreements with the United States. In this sample, the disparity between domestic and imported averaged roughly $3 per 12-pack at $2.96.

In this sample, the disparity between domestic and imported averaged roughly $3 per 12-pack at $2.96.