Let’s set the stage with a scene from a modern marriage:

Me: Honey, your birthday is next week, and it’s a big one. Let’s do something really, really special to celebrate.

My wife: Sounds great! What do you have in mind?

Me: Well, I was thinking of taking you out and buying you the biggest omelet in the city. Three, four, maybe even five eggs.

My wife: Really? Are you sure we can afford it?

Me: We’ll find the money. And besides, I’ve been putting a few bucks aside every week for the past three months just for this.

My wife [eyes filling with tears]: Oh, my dear, dear husband. Do you love me that much?

Me: Yes. Yes, I do.

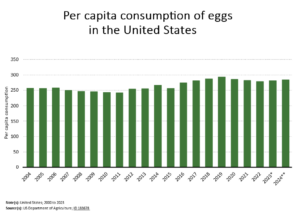

That scene isn’t as far-fetched as it sounds. Eggs are one of the protein staples of the modern diet, with Americans eating about 23 dozen eggs each year. They have soared in price as a nasty strain of avian flu has led to the death of millions of hen layers and other birds across the United States and the rest of the world.

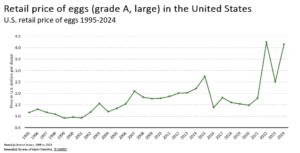

The most pernicious form of avian flu, known as H5N1, is devastating to affected birds. Mortality rates can be as high as 90-100 percent. Even milder forms of the flu can lead to significantly reduced egg production. And with lower yields come reduced supplies and higher prices – per-dozen egg prices now at an average of $4.95…and anticipated to climb 20 percent higher as we move further into 2025.

As noted by www.moneynotmoney.com:

“The absolute price of eggs has increased by $1.54 (80.63%) in the last decade, and $2.61 (310.71%) since 1980.

Even when adjusting prices for inflation, egg prices are still higher than they were in 1980. And not just a bit more expensive, we are talking about a significant increase no matter how you look at it!”

How widespread is avian flu?

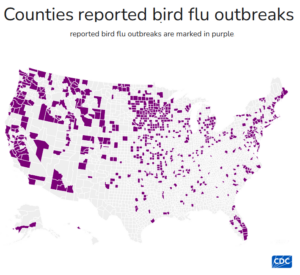

A form of avian flu, called highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), was noted by USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) as far back as February 2022. This particular H5N1 strain was first noted on March 25, 2024, and has been growing ever since.

Last December, USDA said that since 2022 the bird flu had been detected in more than 125 million birds across 569 counties in all 50 U.S. states, in both commercial and private facilities.

Last December, USDA said that since 2022 the bird flu had been detected in more than 125 million birds across 569 counties in all 50 U.S. states, in both commercial and private facilities.

On January 23 of this year, USDA further noted that an additional 98 flocks had been infected in the past month alone, with another 15 million birds affected.

Data from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) also point to the enormous effect of the disease – citing 1,572 reported outbreaks across 641 counties, with 159,307,978 affected in poultry flocks and aquatic birds.

The United Nations says the bird flu has caused the deaths of more than 300 million birds worldwide – involving not just laying chickens but ducks, geese and other kinds of birds as well.

Why are egg layers more at risk than broiler chickens?

The avian flu virus can afflict both egg layers (hens that lay eggs) and broilers (chicken produced for your dinner plate) produced for meat. But so far, the disease has been most damaging to layers, since they live for much longer: a healthy laying hen will start to produce eggs at around 18 weeks old and, on average, five-to-six more years following.

USDA reported in January that avian flu HPAI has been detected in commercial broiler flocks in three states – Georgia, Maryland and Virginia.

USDA reported in January that avian flu HPAI has been detected in commercial broiler flocks in three states – Georgia, Maryland and Virginia.

Broilers also face rigorous testing by APHIS before they leave any farm and additional testing when processed.

The damage to broiler flocks so far has been small enough that supplies closely match demand – meaning minimal price effects. Broiler meat prices are up only about 1 percent from a year ago.

Avian flu’s migration beyond birds

To add to the complicated picture, the virus also can affect other animals.

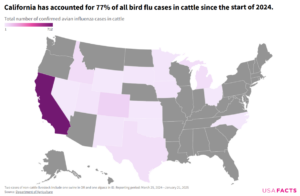

Infection among 929 dairy cattle has been reported across 16 states, with more than three-quarters in California. Isolated and small numbers of infections have also been reported in cats, pigs and even an alpaca.

By any measure, it’s a devastating disease, with resulting concerns about not just the cost of eggs but also the risk to humans and other mammalian species.

Scientific American notes that CDC reports that 67 human cases of H5N1 have been confirmed, most involving mild symptoms. (One case involving the death of a patient with underlying health issues has been recorded in Louisiana.)

CDC notes that such cases involve direct contact between the human and an infected animal, including cows. Cows pass large amounts of the virus in their milk, but pasteurization has been shown to kill the virus.

Is it safe for us to consume eggs right now? Fear not.

As Good Housekeeping reported: “The risk of getting the H5N1 bird flu virus from eggs is minimal to none, and safe storage and cooking of eggs reduces any potential risk,” says Geeta Sood, M.D., ScM, assistant professor of medicine in the Johns Hopkins Medicine Division of Infectious Diseases at Johns Hopkins University in Washington, DC.

What does all this mean for egg prices?

We eat a lot of eggs. USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS) notes that per-capita egg consumption in the United States averaged 284 eggs in 2024. Before the pandemic, the numbers were even higher – in the range of 294.

Swings in egg prices are nothing new. But the most recent increases have been abnormally high, at a time when high food inflation has been a hot topic among consumers and politicians.

Both Joe Biden and now Donald Trump have made control of food price inflation a major goal. The devastating loss of layers – and the significant costs of decontamination, implementing stringent new safety precautions against disease and rebuilding flocks – are adding to the economic pressures facing producers across our food chain.

That’s a Lot of Eggs…

U.S. table egg production totaled 92.6 billion in 2022, a 3 percent decrease from 2021. The U.S. had 308 million commercial laying hens at the end of 2022, down 4.5 percent from 2021. The daily rate of lay averaged 82 eggs per 100 layers in 2022. On average, each laying hen produces 300 eggs per year.

Meanwhile at the grocery store…

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reports that average egg prices in January increased a whopping 19.5 percent from December, rising to an average of $4.95. “This was the largest increase in the eggs index since June 2015 and it accounted for about two thirds of the total monthly food at home increase (in food inflation),” according to BLS.

A local supermarket worker described the retail situation in simple terms: “Eggs come in on Friday’s truck. By Monday, they are pretty much gone.”

A local supermarket worker described the retail situation in simple terms: “Eggs come in on Friday’s truck. By Monday, they are pretty much gone.”

But buying that dozen eggs at the supermarket is only one way the avian flu is contributing to higher food costs.

Eggs are a key ingredient in many prepared foods and an extremely popular food eaten in restaurants, diners and other out-of-the-home dining. Higher egg prices inevitably are passed along in all these venues, adding to the poor consumer’s economic woes.

What’s being done about it?

Avian flu has generated extensive interest from farm to consumer, with a variety of responses.

Layer producers deal with the threat of avian flu with a carefully tiered series of steps worked out with federal and state authorities. When the avian flu is detected, the first step is to quarantine the flock and any equipment that may be around the birds. The flock is then humanely euthanized.

The farm where diseased birds were found is thoroughly disinfected, and the entire farm tested for 21 days to confirm that it is free of the disease. The surrounding area also is monitored and tested for the disease.

The farm community has aggressively sought to get ahead of the disease with extensive prophylactic actions, careful monitoring and testing, and even the personally painful and economically difficult decision to eradicate entire flocks.

Media and industry communications also have sought to raise public understanding of the complex issue and the steps being taken to assure a safe food, in order to avoid over-reaction.

Scientists in various government agencies and the private sector continue to work on understanding the disease and effective methods to combat it. Some of the most aggressive efforts have been focused on development of an effective vaccine against avian flu. That’s not a new idea. But it’s proven to be less straight-forward than it might seem on the surface.

Various avian flu vaccines have been developed since the first avian flu outbreaks in Southeast Asia in 2001-02 and have been used in countries around the world, with mixed success. For example, China and Egypt have used vaccines against the disease, although recurrent outbreaks still happen.

Research in the United States also has produced encouraging results, with one HPAI vaccine produced by Zoetis in February received conditional approval from USDA’s Center for Veterinary Biologics (CVB).

H5N1 & trade implications

But the widespread use of vaccines against the avian flu remains a highly contentious issue. The major reason: use of vaccines could trigger import restrictions for poultry among foreign customers.

Existing and long-standing trade agreements contain stringent requirements for what can and cannot be present in imported foods. Such requirements have been actively used around the world both as a food-safety precaution – and frankly, as a means of protecting national industries.

U.S. agriculture knows this phenomenon all too well. Poultry industry leaders and politicians have been wary of rushing to vaccines, preferring to emphasize prophylactic measures instead.

Poultry is the most-consumed livestock product in the world.

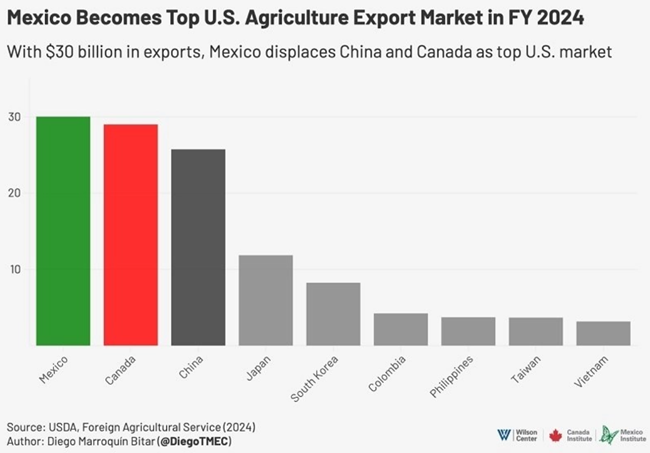

The United States is the world’s largest producer and second-largest exporter of poultry meat. According to USDA data, U.S. broiler exports over the past decade have averaged 7.1 billion pounds per year. USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS) estimates the three-year average of poultry meat and products at $5.66 billion.

Egg exports, including both shell eggs and egg products, last year exceeded 234 million dozen. The three-year average of egg and egg-product exports from the United States is $741 million. Farmers today need the income that comes from poultry and egg trade.

Statista notes that the United States imports about 15 million dozen eggs each year, compared to exports of almost 16 times that amount – and more compared to some other market analysis. Part of the disparity can be traced to simple matters of handling and consumer reaction. In the United States, eggs are carefully cleaned and refrigerated, while most of the rest of the world prefers to leave eggs unrefrigerated.

How long will this go on?

One of the oldest adages in economics (and especially the agricultural world) reads: “the cure for high prices is high prices.”

Egg prices are most likely to moderate when the layer industry has had time to adapt to an extraordinary set of challenges. New facilities must be built and existing ones cleaned, sanitized and modernized with the latest and best sanitary equipment.

Aggressive and where possible better disease control practices must be implemented. High egg prices perversely provide the economic incentives to prompt all those actions.

There also is the issue of the time needed to rebuild flocks. Replacing lost layers will proceed when the remedial protective actions have been completed. It makes no sense to invest in more animals if the proper precautions have not been taken. And once they are replaced, it will take months for the new birds to begin producing eggs.

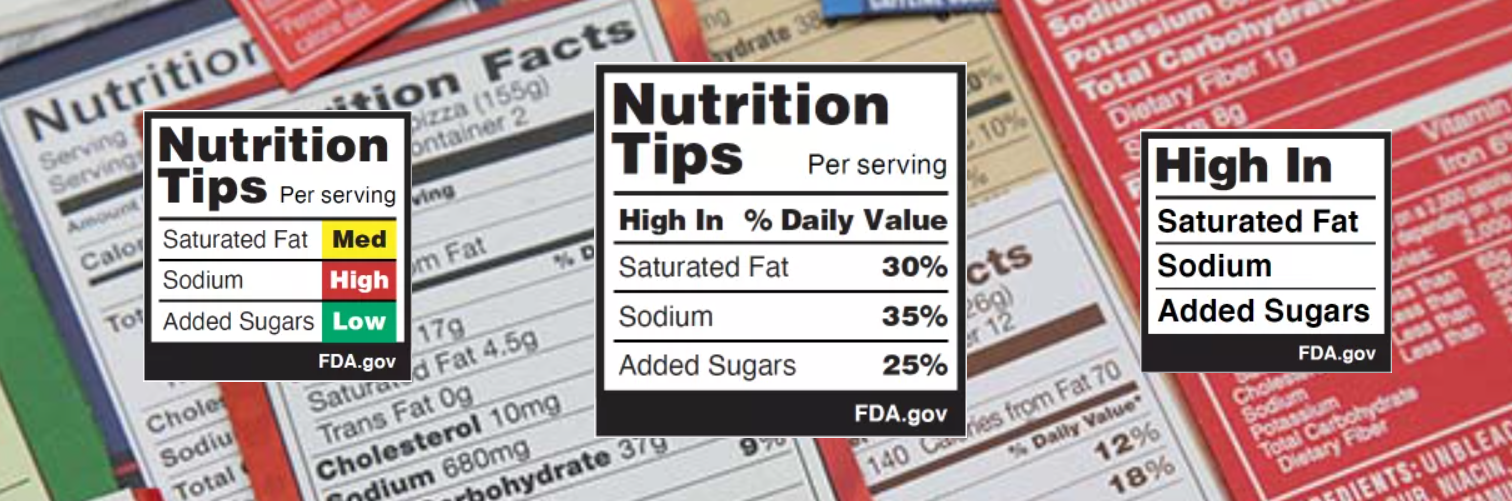

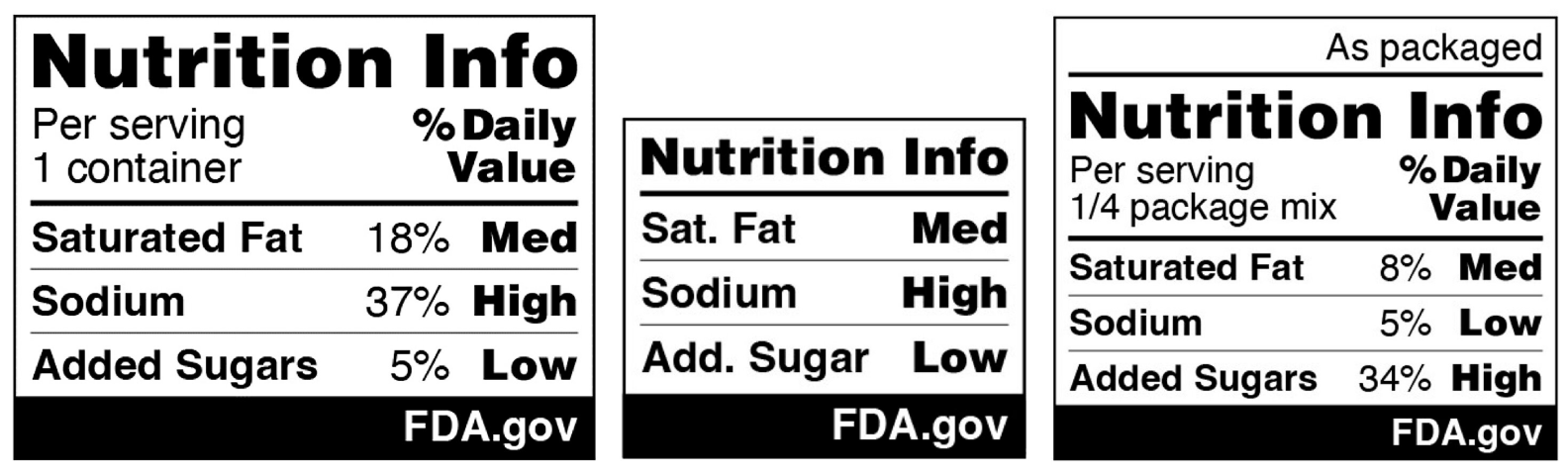

The FDA’s decision to act on Red Dye No. 3 after decades of inaction may signal a shift towards more proactive regulation of food additives.

The FDA’s decision to act on Red Dye No. 3 after decades of inaction may signal a shift towards more proactive regulation of food additives. There are many substitutes for Red Dye No. 3, such as beet juice, purple sweet potato extract, red cabbage extract, carmine, and pomegranate juice. These natural substitutes align with growing consumer preferences for clean-label ingredients. After all, many of us would rather consume pomegranate juice in Jell-o than red dye.

There are many substitutes for Red Dye No. 3, such as beet juice, purple sweet potato extract, red cabbage extract, carmine, and pomegranate juice. These natural substitutes align with growing consumer preferences for clean-label ingredients. After all, many of us would rather consume pomegranate juice in Jell-o than red dye.