A University of California, Berkeley professor stands at the front of the room, delivering her invited talk about the potential of genetic engineering. Her audience, full of organic farming advocates, listens uneasily. She notices a man get up from his seat and move toward the front of the room. Confused, the speaker pauses mid-sentence as she watches him bend over, reach for the power cord, and unplug the projector. The room darkens and silence falls. So much for listening to the ideas of others.

Many organic advocates claim that genetically engineered crops are harmful to human health, the environment, and the farmers who work with them. Biotechnology advocates fire back that genetically engineered crops are safe, reduce insecticide use, and allow farmers in developing countries to produce enough food to feed themselves and their families.

Now, sides are being chosen about whether the new gene editing technology, CRISPR, is really just “GMO 2.0” or a helpful new tool to speed up the plant breeding process. In July, the European Union’s Court of Justice ruled that crops made with CRISPR will be classified as genetically engineered. In the United States, meanwhile, the regulatory system is drawing distinctions between genetic engineering and specific uses of genome editing.

I am a plant molecular biologist and appreciate the awesome potential of both CRISPR and genetic engineering technologies. But I don’t believe that pits me against the goals of organic agriculture. In fact, biotechnology can help meet these goals. And while rehashing the arguments about genetic engineering seems counterproductive, genome editing may draw both sides to the table for a healthy conversation. To understand why, it’s worth digging into the differences between genome editing with CRISPR and genetic engineering.

What’s the difference between genetic engineering, CRISPR and mutation breeding?

Opponents argue that CRISPR is a sneaky way to trick the public into eating genetically engineered foods. It is tempting to toss CRISPR and genetic engineering into the same bucket. But even “genetic engineering” and “CRISPR” are too broad to convey what is happening on the genetic level, so let’s look closer.

In one type of genetic engineering, a gene from an unrelated organism can be introduced into a plant’s genome. For example, much of the eggplant grown in Bangladesh incorporates a gene from a common bacterium. This gene makes a protein called Bt that is harmful to insects. By putting that gene inside the eggplant’s DNA, the plant itself becomes lethal to eggplant-eating insects and decreases the need for insecticides. Bt is safe for humans. It’s like how chocolate makes dogs sick, but doesn’t affect us.

Another type of genetic engineering can move a gene from one variety of a plant species into another variety of that same species. For example, researchers identified a gene in wild apple trees that makes them resistant to fire blight. They moved that gene into the “Gala Galaxy” apple to make it resistant to disease. However, this new apple variety has not been commercialized.

Scientists are unable to direct where in the genome a gene is inserted with traditional genetic engineering, although they use DNA sequencing to identify the location after the fact.

In contrast, CRISPR is a tool of precision.

Just like using the “find” function in a word processor to quickly jump to a word or phrase, the CRISPR molecular machinery finds a specific spot in the genome. It cuts both strands of DNA at that location. Because cut DNA is problematic for the cell, it quickly deploys a repair team to mend the break. There are two pathways for repairing the DNA. In one, which I call “CRISPR for modification,” a new gene can be inserted to link the cut ends together, like pasting a new sentence into a word processor.

In “CRISPR for mutation,” the cell’s repair team tries to glue the cut DNA strands back together again. Scientists can direct this repair team to change a few DNA units, or base pairs (A’s, T’s, C’s and G’s), at the site that was cut, creating a small DNA change called a mutation. This technique can be used to tweak the gene’s behavior inside the plant. It can also be used to silence genes inside the plant that, for example, are detrimental to plant survival, like a gene that increases susceptibility to fungal infections.

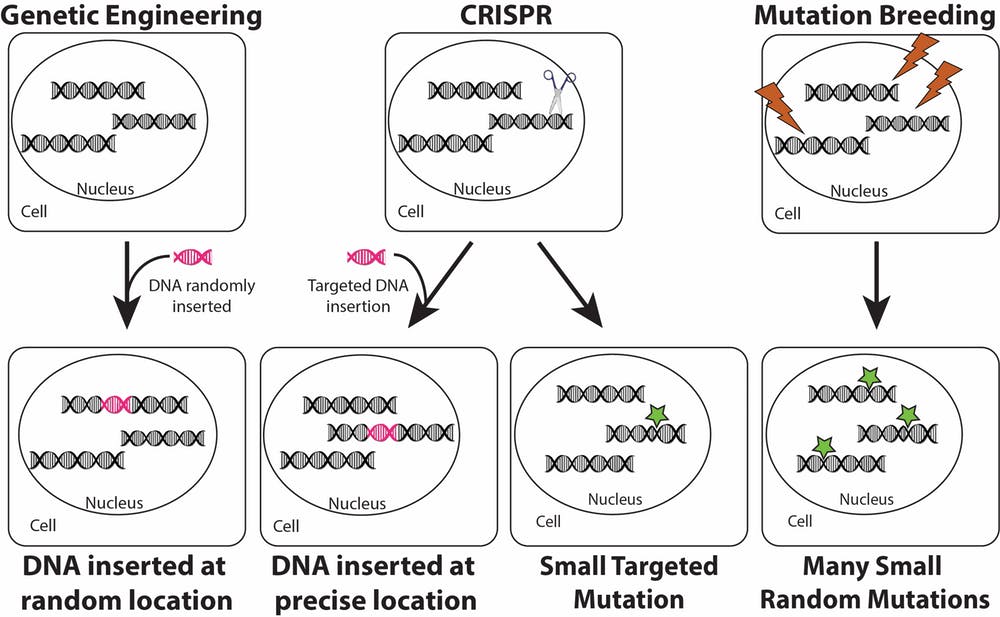

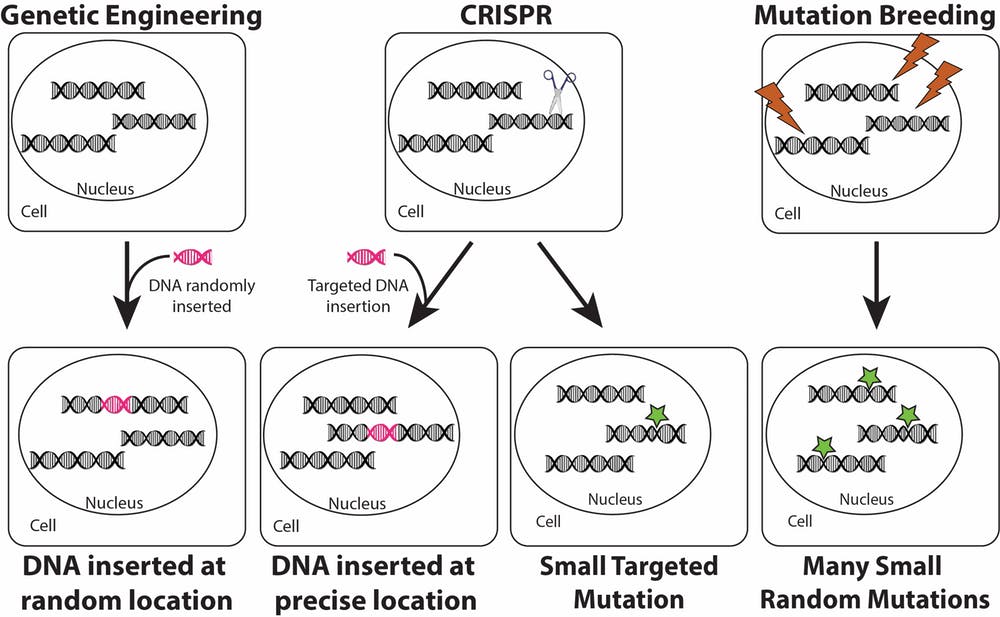

In genetic engineering, a new gene is added to a random location in a plant’s genome. CRISPR for modification also allows a new gene to be added to a plant, but targets the new gene to a specific location. CRISPR for mutation does not add new DNA. Rather, it makes a small DNA change at a precise location. Mutation breeding uses chemicals or radiation (lightning bolts) to induce several small mutations in the genomes of seeds. Resulting plants are screened for beneficial mutations resulting in desirable traits. Rebecca Mackelprang, CC BY-SA

Mutation breeding, which in my opinion is also a type of biotechnology, is already used in organic food production. In mutation breeding, radiation or chemicals are used to randomly make mutations in the DNA of hundreds or thousands of seeds which are then grown in the field. Breeders scan fields for plants with a desired trait such as disease resistance or increased yield. Thousands of new crop varieties have been created and commercialized through this process, including everything from varieties of quinoa to varieties of grapefruit. Mutation breeding is considered a traditional breeding technique, and thus is not an “excluded method” for organic farming in the United States.

CRISPR for mutation is more similar to mutation breeding than it is to genetic engineering. It creates similar end products as mutation breeding, but removes the randomness. It does not introduce new DNA. It is a controlled and predictable technique for generating helpful new plant varieties capable of resisting disease or weathering adverse environmental conditions.

Opportunity lost – learning from genetic engineering

Most commercialized genetically engineered traits confer herbicide tolerance or insect resistance in corn, soybean or cotton. Yet many other engineered crops exist. While a few are grown in the field, most sit all but forgotten in dark corners of research labs because of the prohibitive expense of passing regulatory hurdles. If the regulatory climate and public perception allow it, crops with valuable traits like these could be produced by CRISPR and become common in our soils and on our tables.

For example, my adviser at UC Berkeley developed, with colleagues, a hypoallergenic variety of wheat. Seeds for this wheat are held captive in envelopes in the basement of our building, untouched for years. A tomato that uses a sweet pepper gene to defend against a bacterial disease, eliminating the need for copper-based pesticide application, has struggled to secure funding to move forward. Carrot, cassava, lettuce, potato and more have been engineered for increased nutritional value. These varieties demonstrate the creativity and expertise of researchers in bringing beneficial new traits to life. Why, then, can’t I buy bread made with hypoallergenic wheat at the grocery store?

Loosening the grip of big agriculture

Research and development of a new genetically engineered crop costs around US$100 million at large seed companies. Clearing the regulatory hurdles laid out by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, EPA and/or FDA (depending on the engineered trait) takes between five and seven years and an additional $35 million. Regulation is important and genetically engineered products should be carefully evaluated. But, the expense allows only large corporations with extensive capital to compete in this arena. The price shuts small companies, academic researchers and NGOs out of the equation. To recoup their $135 million investment in crop commercialization, companies develop products to satisfy the biggest markets of seed buyers – growers of corn, soybean, sugar beet and cotton.

The costs of research and development are far lower with CRISPR due to its precision and predictability. And early indications suggest that using CRISPR for mutation will not be subject to the same regulatory hurdles and costs in the U.S. A press release on March 28, 2018 by the U.S. Department of Agriculture says that “under its biotechnology regulations, USDA does not regulate or have any plans to regulate plants that could otherwise have been developed through traditional breeding techniques” if they are developed with approved laboratory procedures.

If the EPA and FDA follow suit with reasonable, less costly regulations, CRISPR may escape the dominant financial grasp of large seed companies. Academics, small companies and NGO researchers may see hard work and intellectual capital yield beneficial genome-edited products that are not forever relegated to the basements of research buildings.

Common ground: CRISPR for sustainability

In the six years since the genome editing capabilities of CRISPR were unlocked, academics, startups and established corporations have announced new agricultural products in the pipeline that use this technology. Some of these focus on traits for consumer health, such as low-gluten or gluten-free wheat for people with celiac disease. Others, such as non-browning mushrooms, can decrease food waste.

The lingering California drought demonstrated the importance of crop varieties that use water efficiently. Corn with greater yield under drought stress has already been made using CRISPR, and it is only a matter of time before CRISPR is used to increase drought tolerance in other crops. Powdery mildew-resistant tomatoes could save billions of dollars and eliminate spraying of fungicides. A tomato plant that flowers and makes fruit early could be used in northern latitudes with long days and shorter growing seasons, which will become more important as climate changes.

The rules are made, but is the decision final?

In 2016 and 2017, the U.S. National Organic Standards Board (NOSB) voted to exclude all genome-edited crops from organic certification.

But in my view, they should reconsider.

Some organic growers I interviewed agree. “I see circumstances under which it could be useful for short-cutting a process that for traditional breeding might take many plant generations,” says Tom Willey, an organic farmer emeritus from California. The disruption of natural ecosystems is a major challenge to agriculture, Willey told me, and while the problem cannot be wholly addressed by genome editing, it could lend an opportunity to “reach back into genomes of the wild ancestors of crop species to recapture genetic material” that has been lost through millennia of breeding for high yields.

Breeders have successfully used traditional breeding to reintroduce such diversity, but “in the light of the urgency posed by climate change, we might wisely employ CRISPR to accelerate such work,” Willey concludes.

Bill Tracy, an organic corn breeder and professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, says, “Many CRISPR-induced changes that could happen in nature could have benefits to all kinds of farmers.” But, the NOSB has already voted on the issue and the rules are unlikely to change without significant pressure. “It’s a question of what social activity could move the needle on that,” Tracy concludes.

People on all sides of biotechnology debates want to maximize human and environmental outcomes. Collaborative problem-solving by organic (and conventional) growers, specialists in sustainable agriculture, biotechnologists and policymakers will yield greater progress than individual groups acting alone and dismissing each other. The barriers to this may seem large, but they are of our own making. Hopefully, more people will gain the courage to plug the projector back in and let the conversation continue.

Rebecca Mackelprang is a postdoctoral scholar at the University of California, Berkeley. This article originally appeared on The Conversation.