If you’ve tuned into The Joe Rogan Experience with FoundMyFitness’ Dr. Rhonda Patrick, or the Eat Move Think podcast with Dr. Stuart Phillips, a professor of kinesiology at McMaster University, you’ve likely heard experts discussing the muscle-preserving power of protein and the appetite-suppressing effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists.

While GLP-1 medications, like Ozempic and Wegovy, are revolutionizing weight loss, their ability to curb hunger raises an important question: Are you eating enough protein to maintain muscle and metabolic health? With leading researchers like Dr. Phillips and Dr. Patrick highlighting the risks of protein deficiency—especially as we age—understanding how to balance GLP-1 therapy with proper nutrition is more crucial than ever.

In this article, we’ll break down what the headlines aren’t telling you about GLP-1 and protein intake, how to avoid muscle loss while using these medications, and science-backed strategies for maintaining your strength and long-term health.

The Role of GLP-1 Medications in Chronic Illness & Obesity

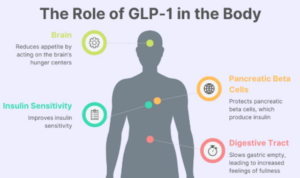

GLP-1 receptor medications, previously just a drug for diabetes, have now emerged as effective treatments for obesity. They function by enhancing insulin secretion, inhibiting glucagon release, and slowing gastric emptying, thereby stabilizing blood glucose levels and promoting weight loss, thus resulting in reduced appetite, decreased food cravings, and lower energy intake.

Clinical trials have shown that liraglutide, the primary compound in GLP-1 medications, resulted in a 3.4% to 6.1% greater mean weight loss compared to placebo, with 50% to 73% of subjects achieving at least a 5% reduction in baseline body weight. As weight drops, the good news is – so does fat. The bad news is – so does muscle.

However, the appetite-suppressing properties of GLP-1s leads to caloric reduction, including less protein consumption. This can have significant health implications if not properly managed.

Why Protein is Essential for the Body

Protein plays a crucial role in various physiological functions:

- Muscle maintenance and growth: Protein provides the amino acids necessary for muscle repair and preservation, especially vital during weight loss or aging.

- Immune system function: Proteins are fundamental components of antibodies, which defend the body against infections.

- Metabolic regulation: Enzymes and hormones, many of which are proteins, regulate critical bodily functions, including metabolism.

- Tissue repair and healing: Protein is essential for the regeneration of tissues, aiding in wound healing and skin health.

- Weight management: consuming adequate protein can reduce appetite, curb cravings, and promote feelings of fullness, leading to a natural decrease in calorie intake.

- Preserving lean muscle mass: muscle tissue burns more calories than fat, even at rest. A study highlighted that individuals who increased their protein intake to 30% of their daily calories consumed 441 fewer calories per day and experienced significant weight loss over 12 weeks.

The Impact of GLP-1 on Caloric and Protein Intake

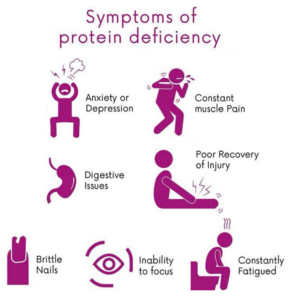

When protein intake is too low, muscle loss becomes a serious concern. Since muscle tissue requires continuous protein intake for maintenance, a deficit in dietary protein can cause muscle atrophy, leading to reduced strength, endurance, and metabolic rate. This can make it harder to sustain long-term weight loss.

Brands like Nestle, Medifast’s Optavia Ascend, Biocare’s high-protein snacks, Herbalife’s GLP-1 Nutrition Companion Protein powders, Smoothie King’s GLP-1 Support Menu, and more have carved out an entirely new food sector to address this issue—protein deficiencies from GLP-1s.

Brands like Nestle, Medifast’s Optavia Ascend, Biocare’s high-protein snacks, Herbalife’s GLP-1 Nutrition Companion Protein powders, Smoothie King’s GLP-1 Support Menu, and more have carved out an entirely new food sector to address this issue—protein deficiencies from GLP-1s.

Inadequate protein intake also weakens the immune system, as the body struggles to produce enough antibodies to fight infections.

Low protein levels can also contribute to chronic fatigue and sluggishness, as protein is essential for blood sugar regulation and energy production.

Those with insufficient protein may experience delayed wound healing, slow muscle and tendon repair, and poor skin health. Protein is a crucial component of collagen production, which aids in skin repair and tissue regeneration.

Given these risks, individuals on medications like Ozempic must take proactive steps to prioritize their protein intake. But how to go about it, and how much do you need?

How Much Protein Do You Need?

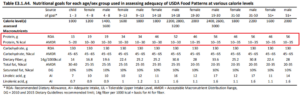

The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) suggests 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight for sedentary adults. This translates to approximately 56 grams daily for men and 46 grams for women.

However, listening to the podcasts outlined above, this baseline is sufficient for everyone. For instance, active individuals or those aiming to build muscle mass often require more protein. Recommendations for such populations range from 1.2 to 2.0 grams per kilogram of body weight.

To illustrate, a 165-pound (75-kg) active male might need between 90 to 150 grams of protein daily. To make it simple, think of eating at least 75% of your body weight in grams.

If you weigh 150 lbs, then eat at least 112 grams of protein.

With Dr. Rhonda Patrick emphasizing the importance of adequate protein intake, especially as individuals age. She notes that the current RDA for protein is insufficient for maintaining muscle mass. Both Dr. Patrick and Dr. Phillips concur that consuming 1.2 to 1.6 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight is likely optimal for muscle protein synthesis, particularly in older adults.

Differences in Protein Needs for Various Age Groups

Protein requirements evolve across the lifespan, much like the changing needs of a growing plant. In children and adolescents, protein supports rapid growth and development.

As individuals enter adulthood, maintaining muscle mass and supporting bodily functions remain priorities. However, in older adults, protein becomes even more critical. Aging is associated with sarcopenia, the gradual loss of muscle mass and strength.

A recent study from Stanford’s Longevity Center emphasizes that adults over 50 should consume at least 1.2 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight daily—higher than previously recommended—to preserve muscle mass and prevent frailty.

For instance, Mr. Thompson, a 70-year-old retiree, noticed a decline in his strength and mobility.

By increasing his protein intake and engaging in resistance training, he improved his muscle mass and overall quality of life.

Identifying and Overcoming Protein Deficiency on Ozempic

Recognizing protein deficiency signals underlying issues that require attention.

Common symptoms include swelling (edema), particularly in the abdomen, legs, feet, and hands, as well as muscle weakness, fatigue, hair loss, and brittle nails.

So what are some ideas for those cutting calories to lose weight to ensure they are getting enough protein?

Especially for those on GLP-1s who have a higher risk of inadequate protein intake?

For example, Emily, a patient managing her type 2 diabetes with GLP-1 therapy, noticed decreased hunger levels.

By consciously adding foods like Greek yogurt, lean meats, and legumes to her diet, she maintained her protein levels and overall health.

Strategies to Ensure Adequate Protein Intake

Ensuring sufficient protein intake while on GLP-1 therapy or otherwise requires deliberate planning. Here are some strategies:

- Prioritize protein at each meal: Start meals with protein-rich foods to ensure consumption before reaching satiety.

- Incorporate protein-rich snacks: Keep convenient options like nuts, cheese sticks, or protein bars accessible for between-meal nourishment.

- Utilize protein supplements: Consider adding protein powders to smoothies or recipes to boost intake without increasing volume.

- Plan balanced meals: Combine proteins with fiber-rich vegetables and whole grains to enhance nutrient intake and promote fullness.

- Monitor intake: Keep a food diary to track protein consumption and identify areas for improvement.

To mitigate the risks mentioned in this article, individuals on Ozempic and similar therapies should actively prioritize protein consumption by structuring meals around high-quality protein sources, utilizing high-protein snacks and supplements, and spreading intake evenly throughout the day.

Special attention should also be given to age-specific protein requirements, as older adults are at greater risk for muscle loss and frailty if protein intake is insufficient. Furthermore, ensuring adequate protein intake post-weight loss can play a key role in maintaining fat-free mass and preventing weight regain.

While we have emphasized eating enough protein, muscles will not build on their own. It is important to do resistance training at least 2-3 hours a week to ensure your muscles don’t decline. As we mentioned in an earlier post, grip strength is an indicator of longevity. It means that you are strong and have muscles to manage your daily activities, plus more.

Ultimately, sustainable weight loss and optimal metabolic health require more than calorie restriction alone—they demand a well-balanced approach to nutrition.

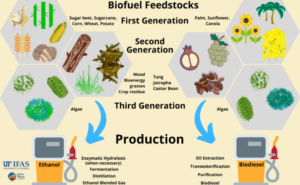

It doesn’t just kill weeds; it kills anything green, including farm crops such as corn, soybeans, cotton, canola, sugar beets, and alfalfa. These crops have all been genetically modified so that the farmer can spray glyphosate after the crop emerges from the ground and kill the weeds, but not the crop.

It doesn’t just kill weeds; it kills anything green, including farm crops such as corn, soybeans, cotton, canola, sugar beets, and alfalfa. These crops have all been genetically modified so that the farmer can spray glyphosate after the crop emerges from the ground and kill the weeds, but not the crop.

While there were different views on its effect on soil health, all agreed that it is the least toxic of the herbicides on the market.

While there were different views on its effect on soil health, all agreed that it is the least toxic of the herbicides on the market.

One farmer invented

One farmer invented

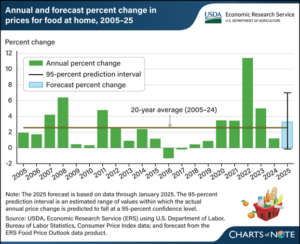

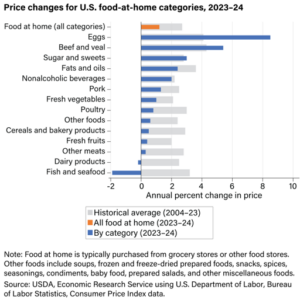

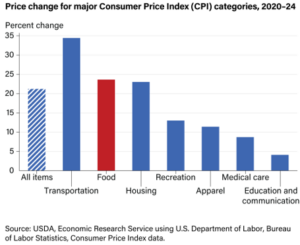

Mostly I look for sales. If it’s a good deal, that’s what we eat.

Mostly I look for sales. If it’s a good deal, that’s what we eat. What do you think? Of course they are going to keep going up. Nothing I can do about that.

What do you think? Of course they are going to keep going up. Nothing I can do about that.  We’ll go out on weekends now and then, but not during the week. And we try to leave the kids home when we do. That saves us a lot of money.

We’ll go out on weekends now and then, but not during the week. And we try to leave the kids home when we do. That saves us a lot of money.

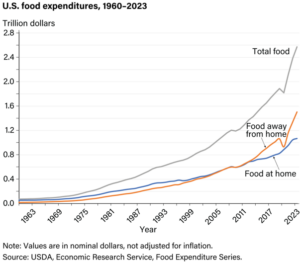

In 2023, over

In 2023, over