Can food packaging & global health coexist?

The Dirt

No matter where you live, plastic is everywhere. This sneaky polymer has woven itself into our daily lives. Every day, plastic’s value shines through by keeping our global food system safer while reducing transport costs and decreasing food waste. But is it too much too late for us to correct unrecycled waste’s disastrous trail across the globe?

Global Food

Can food packaging & global health coexist?

The Dirt

No matter where you live, plastic is everywhere. This sneaky polymer has woven itself into our daily lives. Every day, plastic’s value shines through by keeping our global food system safer while reducing transport costs and decreasing food waste. But is it too much too late for us to correct unrecycled waste’s disastrous trail across the globe?

On the run? LISTEN to our post!

Look around you – how many plastic products do you see? For someone who’s trying to limit plastic use, I already count 12 products in my living room… and I haven’t even gotten to the kids’ toys yet.

But we can’t help it. Plastic makes our lives super convenient and our products cheaper, safer, and longer-lasting. Sadly, this material is also clogging up our waterways and shorelines, killing off species, and devastating our planet. With its approximate 400-year lifespan, most plastics have nowhere to go but up, whether heaped onto a towering pile or incinerated into greenhouse gases.

And almost half of the plastics we go through are from packaging, with food packaging being the largest contributor. This isn’t hard to believe, especially among those of us who order our groceries online.

The last time I received a grocery delivery, I opened up a box lined with a thin plastic film to find my produce individually wrapped in plastic bags. And my more delicate produce was even in a Styrofoam-like sheet within a plastic clamshell within the bag. Talk about Pandora’s box of mismanagement.

And yet, there is a reason for it. In fact, there are several.

A case for plastics

When growing up in a functional food system, it’s easy to overlook the many benefits we take for granted. Take, for instance, food safety. Contaminants like allergens, foodborne pathogens and safety hazards abound as food travels across the globe, so we must mitigate exposure when and where necessary.

With plastic, our global system has made food far less of a threat to our health than before its advent, with practices and procedures that keep our products safer and storing its nutritional content for longer. These coordinated efforts have made food distribution possible during even the worst of times (like during a pandemic).

Packaging also increases the shelf-life of perishable foods, giving us a chance to enjoy fresh raspberries in February and cook fresh Chilean and Norwegian salmon around the world. Without plastic, the raspberries would quickly grow mold and the salmon would harbor a dangerous amount of pathogens. See the chart to the right for more demonstrated benefits of food packaging advancements.

Plastic packaging also lowers transportation costs and fuel needs. Plastic containers can be impossibly thin and infinitely stackable. They’re also more supportive and water-resistant than cardboard, less rigid than tin, and far lighter and more durable than glass.

But isn’t plastic inherently bad? And made from things it supposedly offsets, like fuel and gas? This is where it gets hard to balance plastic’s omnipresence in global commerce.

Oh, it’s definitely bad…

In 2018, food containers and packaging generated more than 82 million tons of waste in the U.S. alone. With 122 million households in the U.S. at that time, that comes to 1,350 pounds of plastic waste per household in a single year.

And unfortunately, it’s only gotten worse. While supermarkets and manufacturers began implementing rigorous greenhouse gas-reducing strategies in the 2010s, the pandemic hit. This event alone reversed the course of seeing sizeable gains in slowing single-use plastic production.

During Covid, plastic production increased by 30% to meet CDC requirements for heightened hygiene efforts and consumer demand for online orders from supermarkets and retailers. Even more concerning, online grocery shopping spend isn’t slowing down anytime soon (see the projection through 2025 below).

To offset this increase in plastics production, Americans are recycling more than ever. Unfortunately, the issue extends beyond our immediate control — it’s in the hands of our municipal recycling programs. And some of these programs are more diligent about recycling than others.

The U.S. has historically sent approximately one-third of its recyclable waste abroad. Since 2018, when China stopped accepting shipments of our plastic waste, the U.S. redirected most of its recyclables to other countries, including Canada, Mexico, and Malaysia.

But as more countries refuse shipments, we are forced to use our own domestic recycling facilities more often. With sudden overuse and little to no budget allocated, these municipal plants grow in disrepair, resulting in only 9% of total recyclables currently getting recycled.

Recycling: breaking down a complicated process

Though the majority of plastic waste isn’t recycled because of lack of proper facilities, it’s also because recycling requires a very precise sorting process. For instance, even the smallest bit of food “contaminates” a potentially recyclable container.

Materials we assume are easily recyclable turn out to be the opposite. Take polymer films, like plastic wraps, grocery bags, and sandwich bags. Throw those into regular recycling bins and they can ruin the whole load. Low-quality, non-recyclable plastic film (often labeled as #4 LDPE plastics) contaminates higher-quality polymers and, due to sorting costs, the entire bin will likely be routed to the landfill or incinerator. So we must pay attention to those recyclable numbers on the bottom of a package.

On the other end of the packaging spectrum is highly complex, multi-layered packaging. Think that organic applesauce pouch or shelf-stable oat milk is recyclable?

On the other end of the packaging spectrum is highly complex, multi-layered packaging. Think that organic applesauce pouch or shelf-stable oat milk is recyclable?

The revolutionary yet complex design is anything but, as this illustration shows. Just recycle the plastic top (not included in this diagram, by the way), and throw the pouch or carton out. Even if it were recyclable, the residue inside can render it “contaminated”.

Some companies freely use the ubiquitous green triangle on their packaging, or tout their products as “organic” or “natural” without any further information or instruction (we’re looking at you, plastic bags and yogurt pouches).

This misleads many of us so we assume that these kinds of containers are universally recyclable. Until companies correct misleading recycling labels, this kind of packaging, plus the load of recyclables they’re combined with, are less likely to get recycled.

“You look at an organic, gluten-free kale chip package and it’s wrapped in seven plastics with undefined inks and metallized polymers. It doesn’t have a recycling symbol on it because you could never recycle it.

Isn’t it astonishing that we would have that much focus on what’s inside the package and so little focus on what’s outside?”

What can all of us do?

While the market is growing for green packaging materials to replace many common plastics, we are still a ways off till we see widespread implementation, especially among common consumer goods. So what can we do to move this process along faster?

As regular grocery store customers, we have an impact and can reroute demand to improve channels and packaging. Even just implementing one or two of these tips can have a meaningful impact on your local recycling system, as well as the greater good of the environment:

- Look for packaging that has the green triangle with the numbers 1, 2 & 5 in it, otherwise it’ll most likely end up in the landfill or incinerated.

- Limit use of thin plastic films (#4 LDPE in above image), like plastic wrap and single-use resealable bags. And instead of recycling these at home, bring these products to grocery stores that recycle the menacing films.

- Refrain from buying products with multiple materials, especially pouches and lined paper products. This includes milk and juice cartons with the screw-top and to-go containers and cups.

- Just because a product is “organic” or “all natural” doesn’t mean it’s recyclable, so be sure to check the recycling label.

- Avoid products with “pointless packaging”, like baby spinach that’s in a clear bag within a plastic clamshell. Packaging like this hurts the whole system.

- Thoroughly wash out all recyclables. Even a small piece of food can render it “contaminated.”

- Buy products with packaging that clearly states that it’s made from recycled materials.

- When ordering food for takeout or delivery, ask the restaurant to exclude cutlery, packets, etc.

- Consider composting, but don’t recycle compostable plastics – that will contaminate the whole load of plastic. Want to compost but afraid of pests or don’t have the space? Some Whole Foods stores have composting available.

- Opt for glass food containers that you’ll use forever, instead of plastic ones.

The best thing we can do for global health?

Only buy what we know we’re going to consume. It’s a holistic solution that decreases food waste and packaging, lessens transport, reduces energy use and greenhouse gases, and improves our health and well-being while being mindful of the next generation.

Remember: everything comes at a cost. It’s tough to put into practice but here are some helpful grocery-store shopping tips.

The Bottom Line

Plastic is here to stay, but hopefully newer, greener materials will offset its production in the coming years. In the meantime, try to create less demand for overpackaged goods and support your municipal recycling facility by properly taking care of the recycling you have. Finally, to prevent food - and thus plastic - waste, skip the unnecessary sales and bulk items and try buying only what you need till your next visit to the grocery store.

Transcript: Why Isn’t Cultivated Meat on Our Dinner Plates?

This is a transcript for the podcast episode, "Why Isn't Cultivated Meat on Our Dinner Plates?" It explores the perplexing limbo of cultivated meat, a technology that remains largely absent from store shelves despite receiving federal safety approval and billions in investment.

Latest in other news...

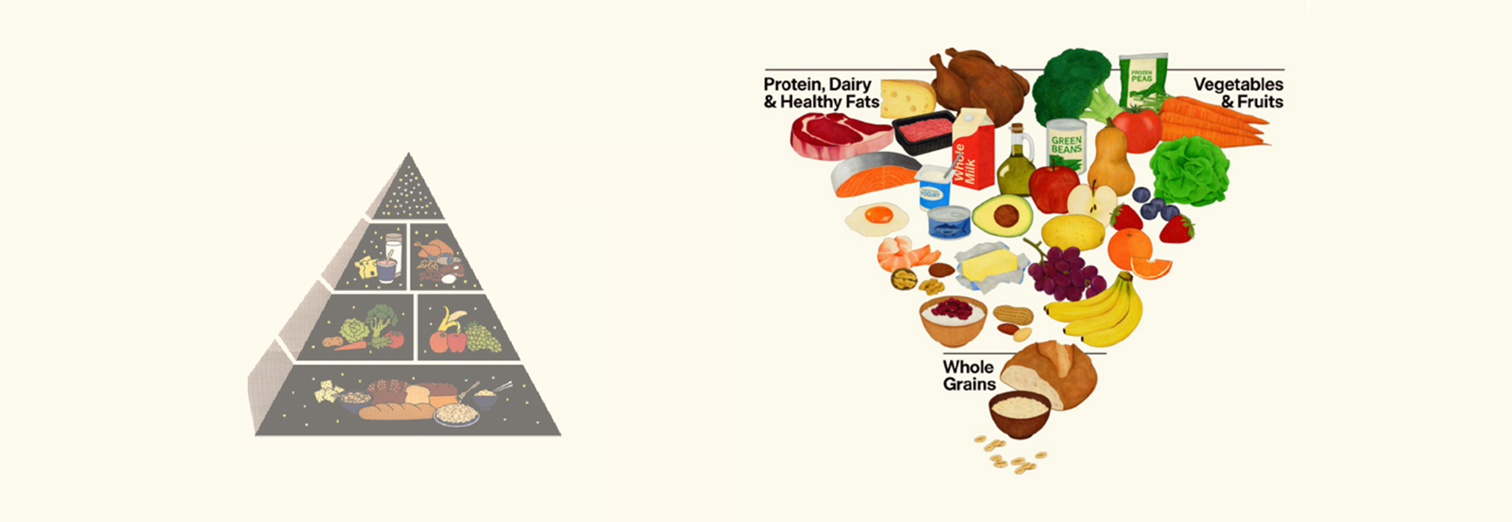

Transcript: The ‘Real Food’ Reset

This is a transcript for the podcast episode, "From Guidelines to Groceries: The Real Food Reset". The new USDA/HHS dietary guidelines marks a “historic reset” in U.S. nutrition policy with a straightforward message: eat real food. But how does this differ from current guidelines?