Venezuela: A Study in Economic Mismanagement

The Dirt

The ouster of Venezuelan dictator Nicolas Maduro has attracted global attention, signaling enormous change and uncertainty for Venezuelans and the country’s relations with the United States and other countries. Food security is at the top of the list of concerns, both to Venezuelans and U.S. agriculture. After decades of government mismanagement of the economy, can Venezuela get back on the road to real food security?

Global Food

Venezuela: A Study in Economic Mismanagement

The Dirt

The ouster of Venezuelan dictator Nicolas Maduro has attracted global attention, signaling enormous change and uncertainty for Venezuelans and the country’s relations with the United States and other countries. Food security is at the top of the list of concerns, both to Venezuelans and U.S. agriculture. After decades of government mismanagement of the economy, can Venezuela get back on the road to real food security?

The situation in Venezuela is indeed a royal mess. Decades of failed government socialist policies have had dire economic consequences for its citizens, including food consumers.

To really begin to understand what’s going on in Venezuela today, we need a little background — just a brief update so we can focus on what’s going on today.

What is behind the crisis in Venezuela?

After more than two centuries of Spanish rule, Venezuela declared independence in 1810 and embarked on the development of its infrastructure and basic economic sectors. Education, along with farming and agriculture, blossomed in the mid and latter 1800s.

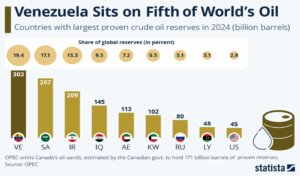

By the beginning of the twentieth century, the country had emerged as one of the world’s largest oil exporters, drawing upon proven reserves larger than any others in the entire world.

With all that oil, it is no surprise that military leadership figured prominently in the political picture, despite the presence of democratically elected governments. The enormous value of oil became both an economic blessing – and a political curse.

With all that oil, it is no surprise that military leadership figured prominently in the political picture, despite the presence of democratically elected governments. The enormous value of oil became both an economic blessing – and a political curse.

Still today, Venezuela has one-fifth of the world’s oil reserves.

In the 1990s, military strongman Hugo Chavez twice attempted government coups before finally succeeding in being elected president in 1998.

Chavez capitalized on widespread public economic frustrations, much of it generated by years of corruption, and lack of economic development benefiting anybody but the elite. In response, he began an aggressive program of greater government control and management of key economic sectors, including food. A small ruling elite – not the marketplace, or sound economics – became the ruling master of the national economy.

Price controls on basic goods – such as food – disrupted markets and led to supply shortages. Land reform in the name of equality took a serious toll on long-standing, successful private farms and ranches. Nationalization of private enterprise spread across not just the food sector but also banking, communications, and especially the oil industry.

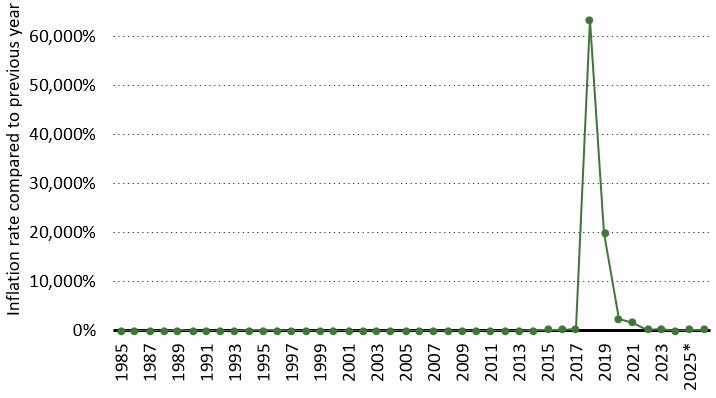

Double- and triple-digit inflation spiraled ever-upward. Market forces were non-existent and government control squeezed capitalism into nothing.

Double- and triple-digit inflation spiraled ever-upward. Market forces were non-existent and government control squeezed capitalism into nothing.

More and more oil dollars were used to fund numerous social programs designed to appease an unhappy public. Sadly, investment in new and better infrastructure wasn’t high on the list of government priorities.

That decision had long-term economic consequences – none of them good. Old, outdated, and inefficient infrastructure across major sectors of the economy would require huge expenditures over a protracted period of time to modernize.

Decades of economic mismanagement and political agendas have created a nightmare environment of inflation and massive price increases, shortages of food and other staples, and significant decline into widespread poverty and despair.

In the early Chavez years, price controls on chicken, beef, pork, grains, sugar, coffee, sugar and other commodities ignored the actual costs of production and fell well below actual market prices. Subsidies from oil income were intended to negate this economic unreality and appease frustrated and angry citizens. Important trade was restricted, shut off, or rendered economically impossible.

Chavez intended his aggressive land-distribution scheme to encourage greater production among smaller landholders. However, his plan failed to appreciate the counter-productive effects of limited access to credit, essential farm inputs and supporting infrastructure. Once again, good intentions (and perhaps a touch of political expediency) ran into the brick wall of economic reality.

When Chavez at last went to his eternal reward in 2013, Nicolas Maduro stepped into power to continue a decidedly socialist approach to economic management. International relations continued to flounder. Election fraud and intimidation ran rampant. Economic sanctions increasingly complicate foreign trade.

And then came perhaps the worst blow of all – a global collapse in oil prices from 2014-2016, falling from $108 a barrel to $57 a barrel. The economic spigot didn’t run completely dry – but a once-torrential flow of petrodollars slowed to a comparative trickle. Barter of oil for services and goods expanded, notably with Cuba.

And then came perhaps the worst blow of all – a global collapse in oil prices from 2014-2016, falling from $108 a barrel to $57 a barrel. The economic spigot didn’t run completely dry – but a once-torrential flow of petrodollars slowed to a comparative trickle. Barter of oil for services and goods expanded, notably with Cuba.

The money simply was no longer there to try to appease discontented – and often hungry – citizens.

Now with our history mini-lesson complete, let’s deal with the real-world issues the different missteps in political leadership have created for everyday Venezuelans – and all the people who play a role in contributing to their food security.

Surprise! The American farmer and rancher are very high on that list.

What does this mean for Venezuelans?

To appreciate just how dire life had become for the average Venezuelan, consider this simple statement from the Human Rights Watch:

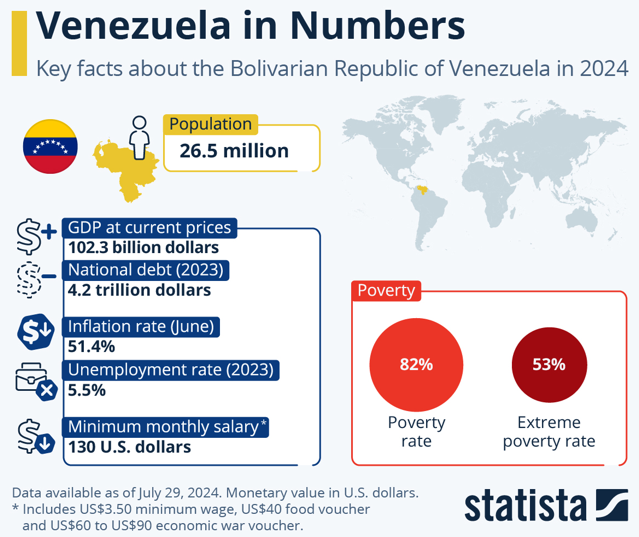

Over 20 million Venezuelans live in multidimensional poverty with inadequate access to rights – essential goods and services, including food and essential medicines.

Many are forced to adopt extreme survival strategies, including fleeing the country.

Today’s population is about 30 million but there has been significant exodus over the past 10 years.

Almost one-quarter of Venezuelans have chosen simply to leave the country since 2014. The United Nations estimates the exodus at 7.9 million people, with an average of 2,000 individuals leaving every day.

Think of it this way… imagine the street you live on. Now think of it with every fourth house suddenly vacant. Imagine the entire population of my small hometown gone – disappeared into thin air – in just eight days.

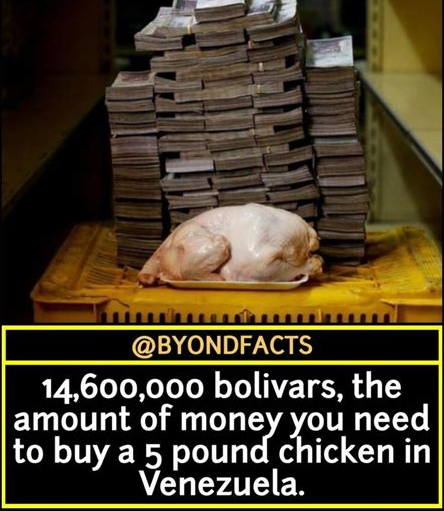

The availability of food – or more accurately, its unavailability or inflated price – has been one of the most significant adverse manifestations of misguided economic policy.

YoY Inflation Rates: Venezuela

Inflation makes it impossible to purchase goods and save money. Inflation today is around 225%. Terrible, but not as bad as it was in 2018.

Shortages run rampant, and prices soar beyond the capacity of average citizens to pay. And to add icing to the cake, the drug trade flourishes, with all the corruption, violence, and social unrest that it brings with it.

Why can’t they just feed themselves?

Historically, Venezuela is not self-sufficient in food. The country has been highly productive and largely self-sufficient in tropical commodities such as coffee, fruits, vegetables, and rice. But vast areas of the country remain undeveloped for modern farming, with only about 3 percent of its total land area used for farming.

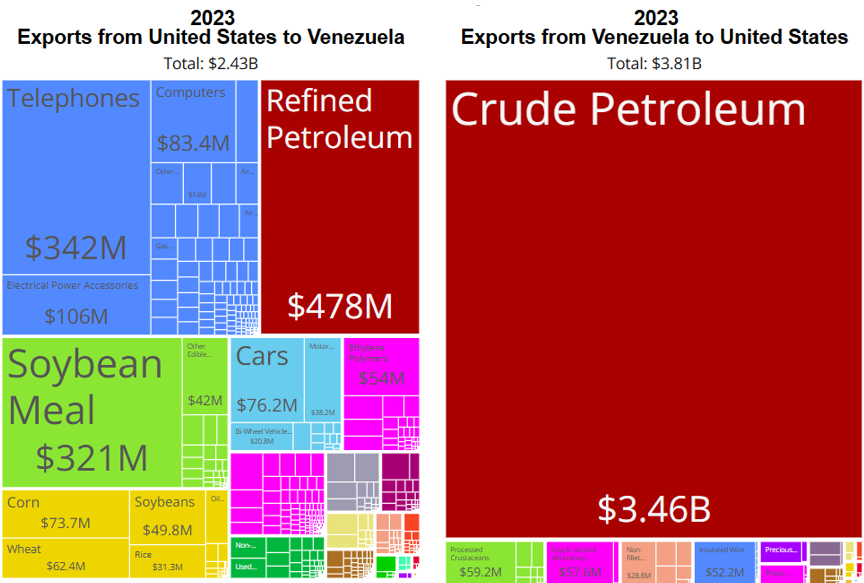

Agriculture accounts for only 5 percent of the country’s entire Gross Domestic Product (GDP). About 70 percent of its cereals and 98 percent of its needed oilseeds are imported. In September 2025, the top exports from the U.S. to Venezuela were soybean meal, wheat, and cars.

Agriculture accounts for only 5 percent of the country’s entire Gross Domestic Product (GDP). About 70 percent of its cereals and 98 percent of its needed oilseeds are imported. In September 2025, the top exports from the U.S. to Venezuela were soybean meal, wheat, and cars.

Price manipulations by the government have been a strong disincentive to many producers. Economic instability has scared off serious investment in developing productive capacity. The government’s blatant seizure of private enterprise only exacerbated the fears. In such an environment, imports have played an important role – arguably a critical role — in helping feed the population of almost 30 million.

What about the poor Venezuelan food consumer?

Failed government policies created shortages and hugely inflated food prices, which have only begun to moderate slightly and begin the tough task of rebuilding food production and consumption.

The economic mess in Venezuela has hit food consumers hard. The United Nations estimates that 82 percent of its citizens live in poverty and 40 percent experience moderate to severe food insecurity.

The main culprit in this sad situation is not the Venezuelan farmer as much as the bad decision-makers dominating the Venezuelan political and economic scene for almost four decades. The country’s animal protein sector provides a good example of how well-intentioned but economically disastrous governmental policies and actions filter down to create an average empty dinner table.

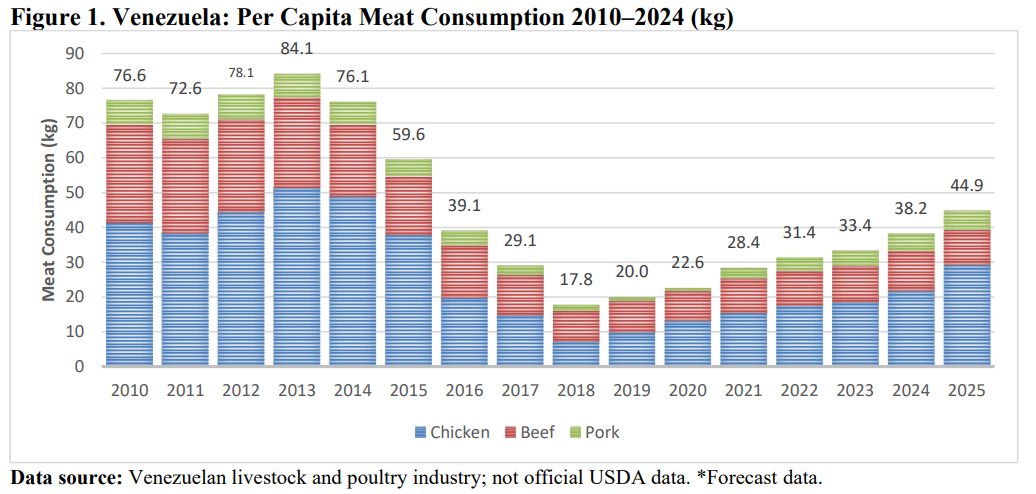

Globally, pork and poultry traditionally provide the most popular sources of animal protein, at roughly one-third each of personal meat consumption. The National Institute of Health Library of Medicine reports that animal protein makes up 70 percent of total daily protein intake for Venezuelans (similar to the percentage for Argentina, and above the roughly 60 percent levels in Peru and Chile).

In the period roughly 2017 to 2019, the full negative effects of attempts to control the food system had become readily apparent. Production and consumption levels for proteins reached a nadir, from which the country is trying to slowly claw its way back to normalcy by allowing the animal protein sector to operate with comparatively fewer governmental controls and dictates.

In the period roughly 2017 to 2019, the full negative effects of attempts to control the food system had become readily apparent. Production and consumption levels for proteins reached a nadir, from which the country is trying to slowly claw its way back to normalcy by allowing the animal protein sector to operate with comparatively fewer governmental controls and dictates.

Reductions in price controls have been a major factor in the rosier sector outlook. The ability of poultry producers to adapt, innovate and invest amid price and control gyrations also has been very important.

Misguided economic policies have severely compromised their ability to fully develop their productive capacity.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates total Venezuelan per-capita meat consumption at 45 kilos (roughly 100 pounds ), up significantly from its 2018 record low. Pork production is projected to rise by about 12 percent, and poultry meat consumption is growing even more quickly — by 40 percent. In contrast, beef consumption is projected to continue its slow decline.

Venezuela boasts a modern, efficient poultry industry, with the potential to meet the needs of the country’s citizens, if allowed to do so.

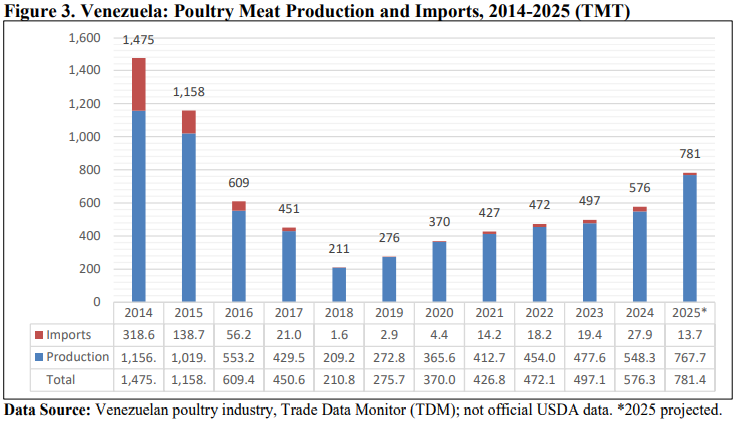

Poultry meat production in 2014 – the year of Maduro’s ascension to power – reached almost 1.5 million metric tons.

By 2018, that figure had declined to 211,000 tons. Poultry meat imports fell from the mid-2000’s levels (318,000 tons at its peak) to virtually zero.

Imports this year are forecast to reach only 14,000 tons. (Historically, most poultry imports come in as processed chicken from Turkey and various forms of poultry from Brazil, Colombia and the European Union.) Industry investment suffered, and more and more people went hungry.

Mark Twain popularized the common quote on the existence of “lies, damn lies, and statistics.”

Venezuelan protein consumption data may well reflect the truth behind the comment.

On a global basis, Venezuela ranks near the bottom quartile in global per-capita consumption of chicken — with at least 111 countries boasting a higher per-capita consumption figure. While we in the U.S. consume almost 120 pounds a year of chicken, Venezuelans are lucky to eat 35 pounds a year.

As positive as the most recent market outlook for animal protein in Venezuela may seem to some, the country faces a long, tough road to joining the front ranks of countries providing consumers with this critical element of a healthful diet.

Where does the U.S. farmer figure into this?

Venezuela relies on the United States for many of its important food and commodity needs. USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service notes that U.S. farmers and ranchers in 2024 had a 39 percent share of the country’s market, worth $800 million.

Venezuela remains an important market for U.S. agriculture, most notably providing many of the grains and oilseeds on which the Venezuelan animal protein sector depends.

Thanks to special exemptions from key trade sanctions, soybean meal, corn, wheat, and rice are top imports – and major factors in the ability of the animal protein industry to recover and expand protein availability for a hungry populace. U.S. trade officials and farm interest all express optimism that the elimination of the Maduro regime will open the door for further growth in Venezuelan market opportunities.

It could well be yet another example of the happy marriage of improved food security (for Venezuelans, in this case) and greater financial opportunity for U.S. farmers.

For more detail on Venezuela, its history and culture check out these sources of information:

BBC Country Profile: Venezuela

The Bottom Line

Venezuela has taken some important steps in addressing the causes of hunger and food insecurity. But the depth and extent of damage from decades of mismanagement are substantial, and they will demand time and money to correct. And in that time, the international community can have an important role to play in assuring that Venezuelan food consumers have the commodities and food products they need to cope and rebuild their country and their lives.

Transcript: Why Isn’t Cultivated Meat on Our Dinner Plates?

This is a transcript for the podcast episode, "Why Isn't Cultivated Meat on Our Dinner Plates?" It explores the perplexing limbo of cultivated meat, a technology that remains largely absent from store shelves despite receiving federal safety approval and billions in investment.