Is Ag the Key to Future U.S.-China Relations?

The Dirt

Tariffs on Chinese goods have become the quiet political rage in Washington. Behind all the talk is an even bigger subject: What’s the future for U.S.-China relations? Just how aggressively does the U.S. challenge China on the world stage? Or can our successful trade relationship in agriculture and food products help teach us another way of thinking about what’s best for both countries?

Global Food

Is Ag the Key to Future U.S.-China Relations?

The Dirt

Tariffs on Chinese goods have become the quiet political rage in Washington. Behind all the talk is an even bigger subject: What’s the future for U.S.-China relations? Just how aggressively does the U.S. challenge China on the world stage? Or can our successful trade relationship in agriculture and food products help teach us another way of thinking about what’s best for both countries?

On the run? LISTEN to our post!

We can’t live with them, and we can’t live without them.

We are sure you have heard this expression before – but not related to an important country with a $17 trillion GDP trying to close in on the U.S. $23 trillion GDP.

Tenuous relations with China

The issues between our two countries are vast: trade imbalance, Covid shutdown, supply chain shortages, intellectual property theft, tariff agreements, Xi-Putin relationship, human rights abuses, Chinese military buildup in South China sea, and worry regarding the Chinese invasion of Taiwan.

“As we face a complex and severe situation in agricultural development and food security worldwide, I firmly believe that China and the U.S., as major agricultural producers, consumers and traders, should meet challenges together, maintain stable development of agriculture, enhance the resilience of agricultural supply chains, ensure food security domestically, and promote cooperation for international food security. This will certainly be helpful for maintaining world peace, promoting global economic development and social stability, and delivering sustainable development.

Let’s bear in mind: no food, no stability, no peace.”

– Qin Gang, Ambassador to the United States, People’s Republic of China

Can our agricultural trade relations put the U.S. on a more equal footing?

The simple facts of mutual self-interest in food are obvious.

China needs a reliable supply of the food and feeds needed to offer improved diets for a burgeoning, increasingly affluent populace.

American farmers need markets for the incredible bounty produced by the most advanced, efficient food system on earth.

And in 2020, China was the largest market for U.S. agricultural exports. For instance, soybeans are 11% of U.S. total exports to China.

The history of U.S.-China trade in commodities and food products reflects those realities.

Phase One of Trump’s Trade Agreement called for China to purchase and import an average of $40 billion annually in food, agricultural, and seafood products for two years (2020 and 2021).

Chinese officials claim the actual 2020 purchases of $26.5 billion reflected the special circumstances facing the world as Covid took hold. In that environment, food and agricultural imports of that amount are noteworthy and still constitute the largest single export market for U.S. agriculture. The U.S. also happened to be China’s largest import market.

Can agriculture help bring our two countries together? It seems that we are at a standoff. Both countries have initiatives in place to be dominant global leaders. China has the Made in China 2025 plan where they have selected key technologies that they strive to dominate globally.

The U.S. Congress has a bill outstanding called the America Competes Act of 2022 which is aimed at reducing long-term dependence on China. The bill includes everything from providing massive subsidies supporting U.S. semiconductor manufacturing to prohibiting federal funding for the Wuhan Lab.

Trade imbalance and tariffs on Chinese imports

The trade imbalance puts the U.S. at risk. U.S.-China trade has increased in value since China joined the World Trade Organization in December 2001. Today, trade between the two countries is $650 billion, give or take a boatload or two of soybeans, compared to $120 billion just two decades ago.

But the U.S. trade deficit has grown quickly, too, along with worries that the imbalance is costing the United States jobs and economic growth. In 2021, the total trade imbalance was $355 billion. The U.S. exported $151 billion to China versus imports totaling $506 billion.

The Economic Policy Institute estimates the trade deficit accounts for as many as 3.7 million lost American jobs between 2001 and 2018. Already in January and February of 2022, the trade deficit was 67 billion, up from 501 billion during the same period in 2021. That alone helps explain Washington’s growing interest in tariffs.

Now let’s combine inflation, a trade deficit, and tariffs. With prices at their highest level in four decades, politicians are grasping for any and all options for reducing the price pain felt by voters in an election year. As more than one public figure has opined, tariffs may be a good negotiating tool, but they serve no strategic purpose and are essentially a tax on consumers.

The most recent Covid shutdown has only exacerbated high prices and inflation. Once again China is in the spotlight for holding up the global supply chain. In their quest for zero Covid tolerance, 26 cities are in lockdown including Shanghai and soon to be Beijing. Citizens are quarantined, factories are partially shut down with employees living on floor mattresses, and global supply chains are suffering.

The United States imports 18 percent of all products from China and 33 percent of electronics. Looks like that new car you might have ordered might not be here by summer.

Timing is everything

But is this the right time to increase tariffs? Psaki and other officials emphasized that the entire question of tariffs remains under discussion within the Biden Administration. They also emphasize that the tariff-reduction and tariff-elimination talks involve “non-strategic goods.”

U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen helped bring the issue out into the open last month in testimony before Congress. Reductions in tariffs on U.S imports from China were “worth considering,” she told lawmakers and the assembled media. White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki later added that the Biden Administration indeed is evaluating the inflationary effects of the tariffs on imports from China imposed by the Trump Administration.

The idea has considerable bipartisan support on Capitol Hill. But efforts to link the issue with further reductions or elimination of tariffs – especially for popular “non-strategic” consumer goods – have proved more contentious.

The political picture has grown more complicated by the much-publicized public polling that shows many Americans still favor the use of tariffs as a lever in building better relations with China. As Forbes reported on a survey from Morning Consult:

“61 percent of voters believe that increased imports have caused the U.S. to become dependent on China for goods that are critical to the U.S. economy and U.S. national security…73 percent of survey respondents said they support the U.S. government using trade remedies on China to protect U.S. industries and American workers with a similar high number – 71 percent – supporting the trade war tariffs imposed on $250 billion worth of China imports during the Trump Administration.

– Kenneth Rapoza, Forbes, April 24, 2022

Take for instance the excitement around emission-reducing electric cars. The world is expected to drive about 400 million of these in the next 20 years. Which country is responsible for extracting rare earth minerals and processing lithium-ion batteries? You guessed it: China. While the cobalt, nickel, and manganese might come from Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile – Chinese state-run companies have a hold on extraction and dominate the processing.

Many politicians agree with those sentiments and argue for the continuation of aggressive tactics to deal with the perceived problems arising from a “one-sided” trade relationship. Some argue against further tariff reductions or exemptions and instead favor ramping up pressure on China to do more to correct the trade imbalance.

One solution would be to bring back manufacturing to the U.S. and reduce our reliance on Chinese imports. This would also address U.S. concerns over intellectual property rights, human rights issues, investment policy, and a host of other matters.

The debate over tariffs fits nicely into the simmering question of how best to revamp U.S. policy toward China. The continuing questions about the direction of U.S. strategy toward relations with China promises to be animated and protracted.

Amid all the arguments, two important points in that debate should be considered…

China is far more inclined to embrace trade in goods essential to citizens’ well-being than in non-essential products. Chinese leaders will look for suppliers who can reliably deliver essentials such as food. With arguably the most efficient and productive agricultural and food system in the world, the United States has the potential to be an important agent in shaping a more constructive relationship between the two countries.

Recognizing and accommodating China’s expanding food needs and objectives – and encouraging a competitive farm and food system to serve those needs and objectives – seems like a more productive approach than mandated quotas and fixed sales commitments.

The Bottom Line

China needs our food. We need markets to improve our trade balance. U.S. agriculture can be a driving force in the new China strategy sought by Washington – one based on mutual benefit rather than overt conflict. “Let's bear in mind: no food, no stability, no peace.”

Latest in other news...

Transcript: The ‘Real Food’ Reset

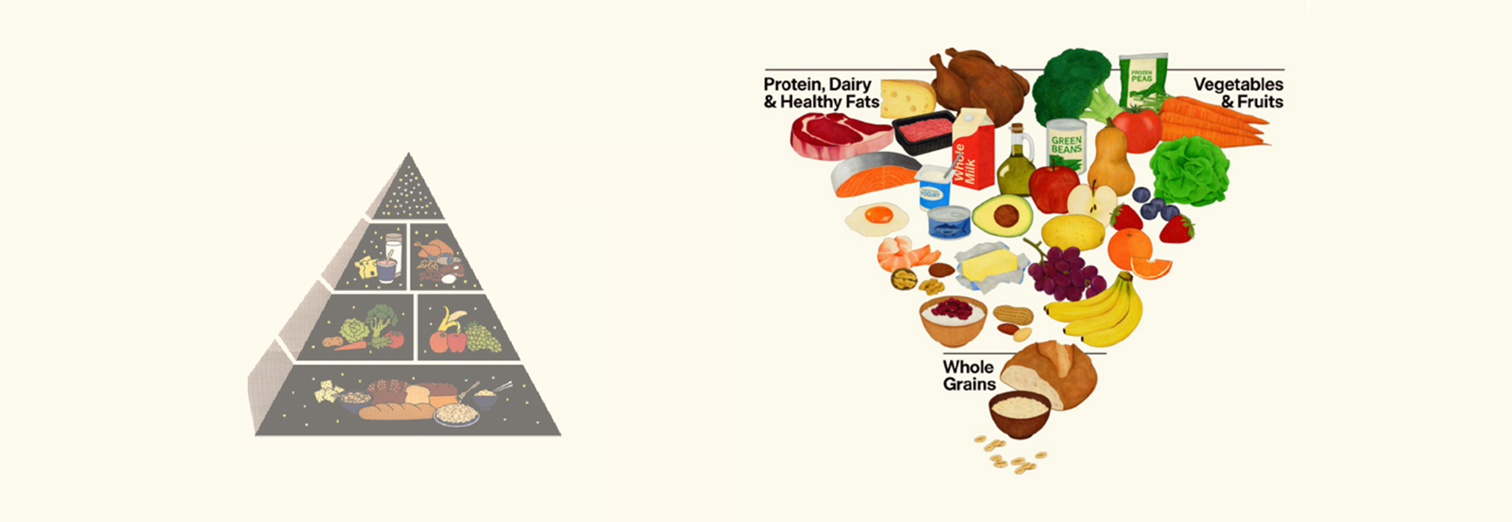

This is a transcript for the podcast episode, "From Guidelines to Groceries: The Real Food Reset". The new USDA/HHS dietary guidelines marks a “historic reset” in U.S. nutrition policy with a straightforward message: eat real food. But how does this differ from current guidelines?