China Assumes Central Role in Global Trade Picture

The Dirt

Think about this: China sells 4 times as many products to the U.S. than we sell to China. BUT, the U.S. sells about five times as much food and agricultural products to China than they sell to us. The U.S.-China relationship is complicated and fraught with geopolitical issues. Will they affect their need for food security?

Global Food

China Assumes Central Role in Global Trade Picture

The Dirt

Think about this: China sells 4 times as many products to the U.S. than we sell to China. BUT, the U.S. sells about five times as much food and agricultural products to China than they sell to us. The U.S.-China relationship is complicated and fraught with geopolitical issues. Will they affect their need for food security?

Trade with China is here to stay. However, this sentence may make you hesitate given all the current geopolitical issues. We have every right to be wary of China: TikTok, Hong Kong, cybersecurity, science & technology theft, Japan/China tensions in East China Sea, China/India border dispute, Huawei. And, not to mention, global GDP is dropping and we are all wearing masks and socially distancing because of a Chinese bat. It is all about a modern-day version of conflict between two political systems: communism and democracy vying for supremacy.

COVID’s effect on global trade

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought a massive chill to global trade, with significant declines in the movement of minerals, metals, petroleum, and many other materials and products playing key roles in our modern lifestyle. But even so, China remains a vibrant participant in the global markets – and none more so than in food and agricultural products.

Rising economic power makes China a major supplier to the world for a wide range of goods – and a major customer for agricultural producers.

Despite these unwanted tensions – and the COVID economic downturn – China is a major import and export market for our farmers and our food. China remains a significant source of many products bought by U.S. consumers, including a range of the foods we consume every day. Just as important, China remains a major market for a long list of commodities and food products grown and processed here in the U.S. that support our domestic farm and rural economies.

China has increased their agricultural imports as they come out of COVID. For the first six months of 2020, year-over-year imports of meat, cereals, and soybeans were up 73%, 9%, and 13%, respectively.

China has increased their agricultural imports as they come out of COVID. For the first six months of 2020, year-over-year imports of meat, cereals, and soybeans were up 73%, 9%, and 13%, respectively.

In part, this is because of the U.S.-China Phase I Trade Deal, where China committed to $36.6 billion of agricultural imports which would provide income for our farmers and ranchers. While they are not on target, there is still some optimism it will be close to budget.

Why should I care about trade at all?

Even though you may have read about the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement, the Trans-Pacific Partnership, and the U.S.- China Trade Agreement, these pacts are not always the first thing on one’s mind when going to the grocery store. But trade is the lifeblood for both our financial health and our dietary well-being. Just about 80% of the calories eaten around the world come in part from another country. When trade lags, our economic interests are at risk, too.

Economists tell us that global trade is 60% of global gross domestic product, or “GDP.” When the GDP rises, it’s a good sign of economic prosperity. When it falls, the news is not so good.

Global food trade is estimated to exceed $1.2 trillion each year. Yes, that is trillion, with a T.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought about a massive downturn in global trade – and projected GDP. The World Bank says the pandemic may create as much as an 8% decline in global GDP – this is of historic proportions. The chart below shows the effect on GDP on the countries hardest hit – those depending on trade.

How important is China in global trade?

China’s role in the international trade picture is enormous, even if it isn’t always recognized by the average person. Since joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, China has grown steadily to become the world’s largest trading nation.

In 2018, China’s combined exports and imports reached $5 trillion, eclipsing the U.S. for the #1 position, further proving their global trading power. Indeed, China is America’s 3rd largest trading partner. As of May 2020, the U.S. exported $40 billion worth of goods to China and imported $144 billion.

It is hard to imagine, but it might be communist China that helps to pull the global economy out of the COVID recession.

The COVID-19 pandemic may have slowed the pace of growth in bilateral and multilateral trade, but it hasn’t completely derailed it.

While the International Monetary Fund predicts a 5% global decrease in GDP, China may be harmed far less than some, at just a 1% projected increase compared to the U.S. at -8% and the EU at a drastic -10%. In 2021, forecasts look brighter, with an 8% spike for China, 6% for the EU, and just 5% in the U.S. once COVID is over.

But can China feed itself?

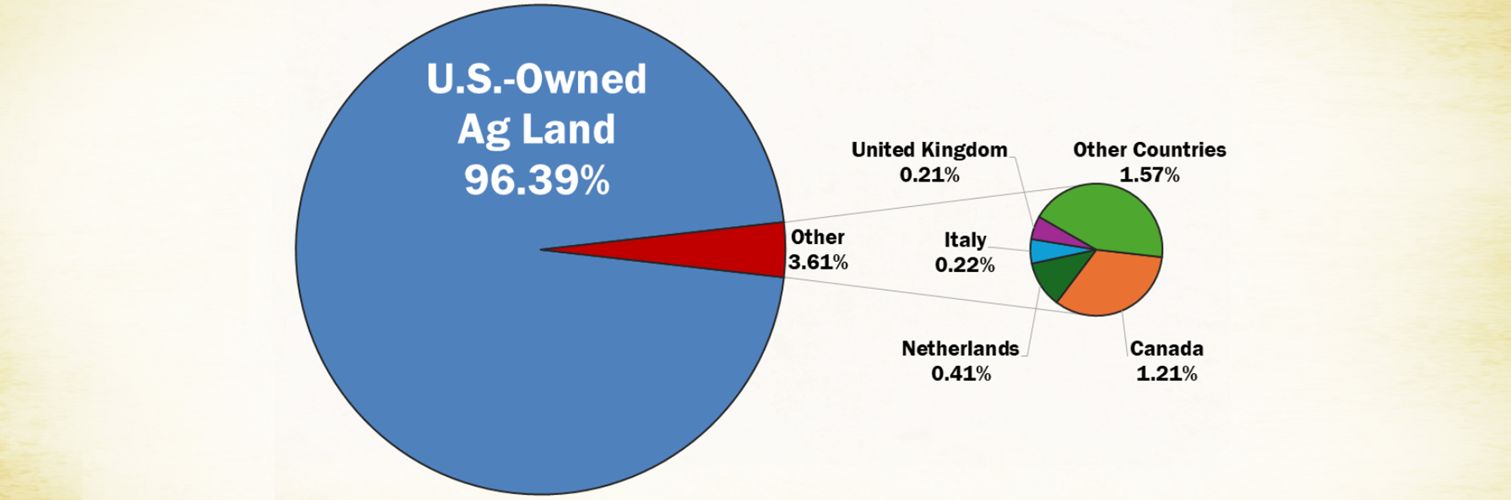

Geopolitical issues aside, the one conversation that keeps the leaders of the Chinese Communist party awake at night is food insecurity. How will they feed a growing population that is moving from the agrarian lifestyle to the cities and suburbs? The U.S. has sold aircrafts, machinery, electronics, optical and medical equipment, and vehicles to China – most of which they can probably make on their own now. But what China does not have is enough arable land.

China has 10% of the arable land, but 20% of the world’s population. Their arable land is 13% of their total land compared to the U.S. at 17%. And, let’s not forget that they have a billion more mouths to feed. This is not to mention that their farming practices are no match for the U.S., as evidenced by their yield per acre and farming efficiency.

Take corn for example: the average Chinese corn producer operates on just a couple of acres or less, with yields of only 90 bushels per acre. Compare that to the average U.S. corn farmer who plants on more than 400 acres and yields about 170 bushels per acre. Some larger, more efficient U.S. commercial corn farms have thousands of acres that hit yields closer to 250 per acre. At this rate, China’s farming efficiency cannot match their population growth.

Agricultural exports to China totaled $25 billion, led by sales of soybeans, cotton, hides and skins, pork, and feed grains. In turn the United States imported almost $5 billion in agricultural products to the United States in 2018, making it the third-largest foreign provider of food and agricultural products. In this case, the trade imbalance is on the side of the United States. Yet we still buy some grocery staples like seafood, juices, garlic, and pet food from China.

So far in 2020, despite the geopolitical issues, China seems prepared to act on that more optimistic economic outlook. But let’s not forget that China has a choice. They do not have to import from the U.S.; they can pivot their soybean, corn, and beef imports over to Brazil and other parts of South America. As you can see, in 2017, China imported more from Brazil than the U.S.

Imports of food and feedstuffs remain a significant factor in global trade, despite the continuing trade bickering between China and the U.S. From a historical perspective, tensions between nations for various forms of superiority and security are nothing new. But tensions between the U.S. and China have serious implications; there’s a great deal at stake for both sides.

The Bottom Line

Geopolitical issues aside, China need the U.S. and other countries to feed their growing population. China’s willingness to continue a vibrant trade relationship in agriculture and food can be seen as a hopeful sign that both nations will continue to find a way out of the highly-publicized trade disputes. There’s just too much at stake.