Will reducing beef save our planet?

The Dirt

At the recent COP28 Climate Summit, the UN stated that wealthy nations should reduce red meat and dairy to avert a global health crisis. But aren't ranchers and dairy farmers proactively reducing its effects already?

Global Food

Sustainable Agriculture

Will reducing beef save our planet?

The Dirt

At the recent COP28 Climate Summit, the UN stated that wealthy nations should reduce red meat and dairy to avert a global health crisis. But aren't ranchers and dairy farmers proactively reducing its effects already?

Are cows really a major cause of climate change? Wealthy nations are not pushing people to switch to a plant-based diet. Will that really work to reduce emissions? What would an all-plant diet for 8 billion people do for the environment? Not to mention that we need 30% of our diet in protein. We investigated this two years ago when Epicurious decided not to include meat recipes and we thought we would post it again given the recent COP28 initiatives.

Every day we choose what to eat. This never used to be a big deal. But today food has become synonymous with politics. I get it. My sister’s family and mine are a close-knit bunch who have mixed views on eating meat. Among our group of children, we have two vegans, two vegetarians, and four meat-eaters.

We love each other a lot and we don’t ask vegans to cook steaks, or the meat lovers to make only plant-based dishes. Instead, we work together to make sure there is enough food for everyone’s plate. Then, we spend our time caring about each other as people, not poking about what we are eating. It is a matter of respect and support for everyone’s choice.

What’s the beef with the UN FAO’s stance on red meat?

At the recent COP28 Climate Summit in Dubai, the United Nation’s Food & Agricultural Organization (FAO) stated that developed nations will need to reduce red meat and dairy production to avert a global health crisis.

I have casual conversations with friends and acquaintances who are diligently participating in ‘Meatless Mondays’ or even skipping red meat altogether because they think they are doing a good deed for the climate.

“According to a new roadmap from the world’s peak food security body, wealthy countries will need to cut back meat and dairy consumption to hit health and environmental targets.

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the UN roadmap outlines a way to feed the world over the next 25 years without increasing the emissions and land clearing that drive climate change and biodiversity loss.”

So, is this true? If we significantly reduced beef and dairy output, would we also significantly reduce emissions? Here is a better question: what if everyone knew that meat can be part of a broader climate solution instead of a climate problem?

We want to give you a more nuanced, data-driven perspective so you can come to your own conclusion.

Cows solving climate change?

Raised in Minnesota, I can tell you there is no more beautiful sight than the grasslands. In the late ‘60s, my bedroom window overlooked a wetland prairie. Whether you think of them as prairies, pampas, steppes, or savannas, about one-third of our global land is open grasslands…tall grasses blowing in the wind, full of deer, elk, songbirds, wildflowers, and cattle.

In a recent post, The Nature Conservancy highlighted a metanalysis, “Reducing Climate Impacts of Beef Production”, showing that ranchers, particularly in the U.S. and Brazil, who own both grasslands and beef can cut emissions by 50%.

As a 1,000-acre rancher in South Carolina told one of us at D2D, “I am really a grass farmer.” When cattle roam freely, their hooves dig up the earth, seeds drop in from neighboring plants, manure adds fertilizer, and the grasslands thrive. The open land thrives because it is a carbon sink.

As Meredith Ellis, a cattle rancher from Texas told us, “our ranch is sequestering 2,500 tons of carbon (after enteric emissions) each year – equivalent to taking 551 cars off the road.”

Grass-fed and feedlot finished?

Did you know that about 95% of all cattle start their lives on grass and then finish the last third of life in the feedlot? Many argue that once cattle are in the feedlot, they contribute to the atmospheric methane, but it is actually the opposite: grass-fed cattle emit approximately 20% more methane because it takes them about a year longer to reach market weight.

Because of the tremendous environmental benefits of grassland, we are not saying that all cows should be raised in a feedlot, but to point out that corn-fed cattle simply produce less methane.

Additionally, many animal nutrition companies are currently researching for the ‘holy grail’ in animal feed to further reduce the release of methane anywhere from 3% to 50%. The reason? More belching occurs when cattle eat the roughage in the grass versus a highly nutritious and tailored feedlot diet. It is when the roughage breaks down that methane is produced.

Moooving over for dairy to digest methane

Dairy farmers also find ways to contribute to a more sustainable environment, too. The dairy industry has benefited from anaerobic methane digesters for years. Dairy farms collect the cow manure and plow it into rubber-lined ponds right next to the barns.

Each of these coverings looks like a dome and helps capture methane. And then, to make a long story short, methane is used as electricity for the farm or sold back on the grid.

These farms have cheap electricity and are greenhouse gas (GHG)-negative because they use methane rather than fossil fuels. In fact, California has committed to a 40% reduction of dairy methane emissions by 2030 just by using digesters alone.

Just to give you an idea of the importance of animal feed, let’s take a look at India…

Just to give you an idea of the importance of animal feed, let’s take a look at India…

They have 56 million dairy cows, more than the E.U., Brazil, U.S., and Russia — combined. Of course, they don’t eat their cows; they just use them for dairy products.

Because their feed and milking systems are not as sophisticated, a cow only produces 2,600 pounds of milk a year versus the U.S.’s 21,000 pounds per cow, on average.

Therefore, India needs eight more cows to give the same amount of milk as one U.S. cow. And at 6 million head, China’s dairy cows have a similar production rate as India.

That is a lot more methane!

What if we don’t eat beef at all?

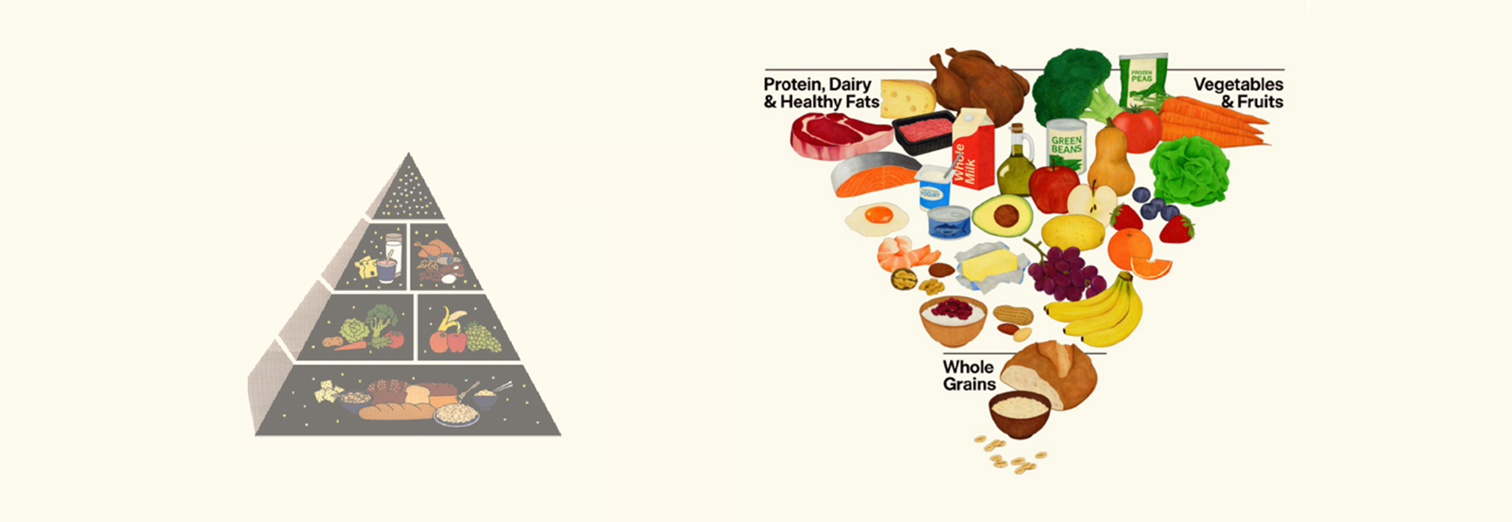

Lean meats and plants are critical for our health. (Have you had your 3-5 servings of fruits and vegetables today?) But the nutrients that meat provides are critical, too. What would happen if all we had to choose from were only plants and grains? To find out what an animal-free country would look like, Robin White and Mary Beth Hall of the Department of Animal and Poultry Science at Virginia Tech and U.S. Dairy Forage Research Center, studied the impact of a vegetarian country on U.S. emissions, economics, and nutrition.

In short, White and Hall found a reduction in emissions of 2.6%, or 28% of agricultural emissions. They explain that there would be 23% more food but deficiencies in U.S. nutritional requirements of minerals, vitamins, and fatty acids. For example, eating a lean 8-oz. piece of steak provides you with 45 grams of protein, versus eating a cup of black beans with only about 15 grams. You get more protein with fewer calories.

There would also be an economic impact. What do we tell the ranchers, farmers, feeders, processors, marketers, and more who have invested billions of dollars creating protein for human health, not to mention the trickle-down effects on local economies?

Cows are carbon neutral. Really!

Despite popular thinking, the reality is that cows are neutral carbon emitters! How? Over time, they do not emit more carbon than they eat. It is undisputed that plants pull carbon dioxide (CO2) out of the air and then combine it with water and sunlight to make carbohydrates and oxygen. The plants use carbohydrates as fuel for growth and emit oxygen into the air as a byproduct. Very handy for us as we need that to breathe.

When a cow eats a plant, it consumes carbohydrates – which contain carbon. It swallows the plant into their four-chambered stomach. The first chamber is massive and holds enough food to fill your bathtub – about 50 gallons. After the plant enters their stomach, they bring it back up to chew some more – “chewing their cud.” The food then goes back down to the stomach to be digested by the microbes, called methanogens.

When a cow eats a plant, it consumes carbohydrates – which contain carbon. It swallows the plant into their four-chambered stomach. The first chamber is massive and holds enough food to fill your bathtub – about 50 gallons. After the plant enters their stomach, they bring it back up to chew some more – “chewing their cud.” The food then goes back down to the stomach to be digested by the microbes, called methanogens.

This is when they belch a portion as methane which is then released into the atmosphere. This methane is the culprit, as it is 28 times more potent as a GHG than CO2.

The good news is that it only lasts for about eight to ten years before it converts into one part CO2 and two parts H2O via hydroxyl oxidation.

Here is where it gets interesting: according to Frank Mitloehner, Ph.D., Professor and Air Quality Specialist at the University of California, Davis:

“If you are not adding additional cattle or cows to the earth, then there will be no additional methane and no additional global warming.”

As long as more cows are not introduced on the planet, then no additional CO2 is added. For the past ten years, global cattle population has been steady at around 1 billion, yet the average annual presence of methane has steadily increased. Dr. Mitloehner continues, saying “We in agriculture have to do our part but must not be singled out as the 800-pound gorilla we are not.”

Sources for chart: noaa.gov, U.S. Department of Agriculture; USDA Foreign Agricultural Service; ID 263979.

Putting this in perspective

So where does agriculture stand in relationship to global GHG contribution? According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, it is about 12%.

There is no doubt that methane is a powerful GHG that we want to keep out of the atmosphere. But it does not all come from animals. According to NASA, the methane sources can be broken out as follows: 30% wetlands, including ponds, lakes, rivers; 30% related to oil, gas, and coal extraction; 20% by agriculture, including livestock, waste management, and rice cultivation; 20% wildfires, biomass burning, permafrost, termites, dams, and the ocean. Here are more detailed breakdowns:

Freedom to Choose

We are already so divided as a country on a variety of political and social issues. Why are we doing this with food and our climate? Yes, cattle emit methane. That is a fact. It is also true that humans have creatively adapted to a life of comfort and health for thousands of years. Let’s use methane reduction for cattle as a lesson in innovation to make our food and our planet better. Let the science speak for itself and not let emotions get carried away.

I quickly recall my family and I debating issues at the dinner table, but at the end of the day, we respect each other’s thinking. We are environmentalists. We are fierce advocates of sustainable food, innovation, and making the world a better place while also being pragmatic about protecting humans and animals. And we also realize how incredibly fortunate we are to choose what we eat each and every day.

The Bottom Line

Eliminating an entire industry where millions of people around the world depend on cattle and dairy to provide protein is not necessarily the answer. The climate roadmap can include better genetics, improved animal feed, better animal health, and restore grazing on pastureland. The success around climate policy includes ‘thinking outside the box’.

Stalled Trade Deal Threatens U.S. Food System Gains

A carefully negotiated trade agreement between the United States and the European Union could open the door to expanded market opportunities for U.S. farmers and ranchers. But can both sides find a way around the other political disputes that threaten completion of the deal?

Latest in other news...

Transcript: The ‘Real Food’ Reset

This is a transcript for the podcast episode, "From Guidelines to Groceries: The Real Food Reset". The new USDA/HHS dietary guidelines marks a “historic reset” in U.S. nutrition policy with a straightforward message: eat real food. But how does this differ from current guidelines?