Why produce aisles look so barren right now…

Global Food

Why produce aisles look so barren right now…

Dirt to Dinner is pleased to have Richard Owen contribute his knowledge and expertise to our site. Richard is Vice President at the Produce Marketing Association, where he has worked since 2009. Richard’s career includes serving as Director of Agricultural Affairs at the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative where his portfolio included Russia, Eastern Europe, India, Indonesia, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, South Africa, and Israel. Richard also served as head of the Airline Passenger Experience Association, Montana Grain Growers Association, and National Association of Wheat Growers Foundation.

The Dirt

Many of us see the lack of fresh fruits and veggies in some of our supermarkets, but we hear on the news about produce wasting away in the fields. How is this happening? And will it get better?

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, you may have gone into your local grocery store and noticed that the full range of fresh produce you’re accustomed to seeing is no longer available. It could be limited supplies of some apple varieties, only one type of lettuce, or no table grapes. What you are experiencing is the disruption of a very complicated supply chain that brings a highly perishable agricultural product from all corners of the world to your local supermarket. All made much more challenging by the multi-faceted complications of COVID-19.

The issue is made more challenging when you consider that in 2018, Americans spent $678 billion on food from full-service and fast-food restaurants, compared to the roughly $628 billion spent at grocery stores, according to USDA. Furthermore, Politico reports that about 40% of fresh produce grown in the country goes to food service, and the remainder to retail.

So in reality, you have two unique supply chains: one serving retail, and one serving the food service sector.

The Produce Supply Chain

According to Nielsen, U.S. fresh produce sales at the retail level was $61 billion in 2018. The product, whether it’s fruit or vegetable, originates on a farm. That farm could be in the U.S, Mexico, Canada or another country in the world. Starting almost at the time of harvest, if not before, the product is picked and, in some cases, grown with the end destination in mind.

Take a banana for example. If it’s going straight from the farm to a restaurant, it will be picked close to ripeness. If it’s going to the grocery store, it will be picked well before ripeness so it has a chance to ripen in the home. Even the container size is different. If it’s going to a food-service distributor like Sysco, it will go in a bulk container without specialized packaging. Broccoli is a good example where it will be bagged for a restaurant and just loose for the consumer in a grocery store.

Or, for instance, the frozen blueberries used in Wyman’s brand of products are bred to be hardier to last through the freezer period. On the other side, you have a different variety of blueberries from Driscoll’s that are made to last in the clamshell packages you find at the market.

Distribution along the Chain

For retail, it’s often branded along the way, whether that be a prominent name familiar to many consumers, or a retail store brand. Retailers often have their own specs for size and quality of certain produce items. For example, Walmart might even have a different grade for different markets based on demographics. As a side note, a system for tracing the product through the supply chain for food safety purposes is similar whether it’s for retail or food service.

Large brands, such as Driscoll’s or Sunkist, typically have contracts to supply retailers and major food-service distributors with their products. They assure product supply by either operating their own farms, but often have contracts with many growers to produce and deliver specified products directly to the major brands. The specs typically include the variety and quantity to be grown, time frame for delivery, and compliance with food safety and specific Good Agricultural Practices.

Mid-size, smaller, and independent growers may sell to multiple distributors, or even directly to retailers. Local retail markets are especially important when produce is in-season. For example, locally grown tomatoes, blueberries and peaches are delivered to retailers less than 100 miles away, as is the case with Heinen’s grocery stores in the Midwest. Also, seasonally, an important outlet for produce are local farmers markets.

How has COVID-19 Impacted Produce?

The impact of COVID-19 on the procurement process is manageable. Most relationships for purchasing are grounded in contracts, along with the need to communicate by phone and e-mail, something that can easily be done from a home office or other alternative.

But a bigger challenge is the highly perishable nature of fresh produce. When a product, say tomatoes, are ripe in the field, they need to be harvested within a short window of several days. If the retailer or food-service distributor is not able to take delivery, you can’t just put the crop on hold and pick it up in a week.

The product needs to be harvested, or the entire crop will deteriorate.

It then carries over into the planting window for the next crop going on the same piece of ground.

Labor for harvesting the crop is also carefully timed to match the predicted ripening and picking date. If a crop is delayed for harvesting due processing delays or closures, the crew may already be scheduled to move to the next crop or farm.

Transportation plays a huge role in the fresh produce supply chain. In the United States, most fresh produce moves by truck. The most perishable of products, like raspberries, can move by air if the market demands it and the customer is willing to pay for it.

At the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak, trucks were in tight supply and freight prices were elevated as many industries competed for a limited number of trucks in the system. Most fresh produce requires refrigerated trailers to travel longer distances, which are always in demand. The supply and demand of trucks are now in more equilibrium as the supply shifts have become more transparent.

Directing Supply to Those in Need

The government also regularly procures fresh produce for military institutions, schools, universities, and aid agencies. With the passage of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act in mid-April, the government will play an even larger role by providing $100 million per month to fund produce distributors and growers to deliver directly to food banks, food pantries, churches, and non-profit organizations serving citizens in need.

The purpose is to provide an alternative way of getting food directly from the field to the neediest at this time of lost jobs, furloughs and disrupted economies. This is a completely new venture for the U.S. government, and everyone will be watching closely to see if this can take some pressure off the current supply chain.

And speaking of food banks, the COVID-19 pandemic has created unprecedented demand on food donation agencies. Reports of a 70-100% increase in the number of food bank customers are common in almost all regions of the country. But many food banks have no or limited ability, if any, to store perishable fresh produce in refrigerated storage for ongoing distribution.

And food banks are now operating with fewer volunteers due to social distancing requirements intended to prevent further spread of the coronoavirus. So, this combination of lack of storage and staffing means that not all produce that is left in the field can make its way to food banks or related distribution routes. The industry has been stepping up and providing refrigerated trucks for use at food banks where possible.

Will the Waste Continue?

So, all this brings us back to a hard truth. The distribution of fresh fruits and vegetables is a complicated endeavor, made even more difficult by the many constraints added by the COVID-19 pandemic. While there are some incidences of produce going to waste in the field, these will only be temporary as the supply chain adjusts to whatever this ‘new normal’ turns out to be, similar to what the meat industry is experiencing, as well.

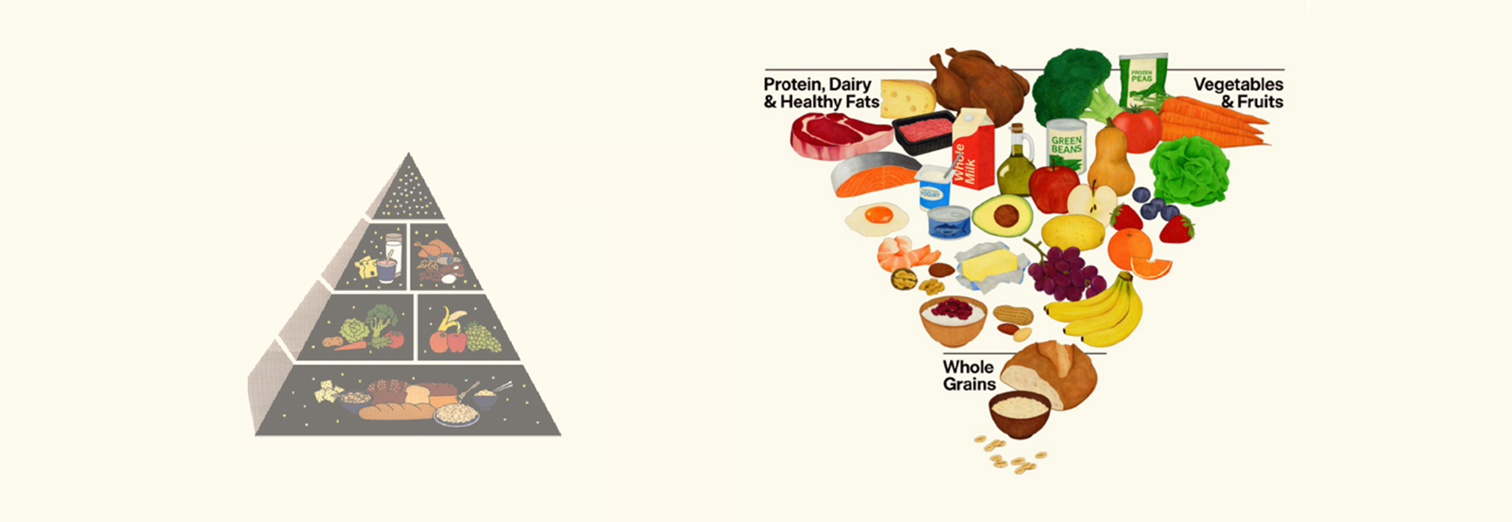

But our part in helping the produce industry during this time is by eating your 5-7 servings of fruits and vegetables every day. Not only does this help the industry to better find its supply-demand equilibrium, but it’s unquestionably good for us, as well. Strengthening our immune systems with healthy, nutrient-dense foods is more important now as it’s ever been. Just make sure not to fall into the panic-buying trap so there’s enough for everyone in your community.

The Bottom Line

Fresh produce demands a production and distribution cycle unlike anything else in the industry. Its perishability, crop timing, and demanding distribution guidelines make it a challenge to balance supply with demand. But by adding more fruits and vegetables to your diet, you can simultaneously help our farmers better manage supply while improving your body’s immune function during this time.

Stalled Trade Deal Threatens U.S. Food System Gains

A carefully negotiated trade agreement between the United States and the European Union could open the door to expanded market opportunities for U.S. farmers and ranchers. But can both sides find a way around the other political disputes that threaten completion of the deal?

Latest in other news...

Transcript: The ‘Real Food’ Reset

This is a transcript for the podcast episode, "From Guidelines to Groceries: The Real Food Reset". The new USDA/HHS dietary guidelines marks a “historic reset” in U.S. nutrition policy with a straightforward message: eat real food. But how does this differ from current guidelines?