Around the World at My Local Restaurant

The Dirt

As I sit here in my favorite local restaurant for the first time in nearly six months, I should be thinking about how much I enjoy this. Even with the social distancing, masks and gloves on the wait staff, and the occasional look of worry and concern I see on the faces of the people around me. After a half-year or more of Covid-19 separation from my old and beloved way of life, this feels really good. And then I take a step back to see the larger picture, even beyond Covid...

Global Food

Around the World at My Local Restaurant

The Dirt

As I sit here in my favorite local restaurant for the first time in nearly six months, I should be thinking about how much I enjoy this. Even with the social distancing, masks and gloves on the wait staff, and the occasional look of worry and concern I see on the faces of the people around me. After a half-year or more of Covid-19 separation from my old and beloved way of life, this feels really good. And then I take a step back to see the larger picture, even beyond Covid...

Finally getting out for a meal makes me appreciate our amazing food system even more than usual – and marvel at how important trade is to it, and to the consumers who depend upon it.

But once again, I realize that I am a junkie. I take great pride in being a true “global food junkie.” I LIKE it. I’ve eaten in fine Parisian restaurants, a mud hut in Ethiopia, a vendor’s stall in Nigeria, a city square in Bangalore, a BBQ shack in Lexington, North Carolina, the famous Carnivore in Nairobi, a Soviet hotel ‘restaurant’ before the fall of the wall, a village festival outside Sevilla, a field workers’ shack in Zimbabwe, a university food hall, a Singapore food market, a Boundary Waters’ campfire…and somehow, I’m still alive.

And here I am in my local restaurant. I’m not so much enjoying the excellent food, marveling at the choices available to me on this menu, slavering in anticipation of the sheer epicurean joy in what I will be served, or savoring the sweet satisfaction of seeing other people again. I find myself thinking that here in a small town in the rural south, in a modest typical country restaurant, I’m really dining out in a much bigger, more diverse world than I’ve ever fully appreciated. I’m truly dining out – dining out not on the town, but on the great big world.

You see, in this modest meal at a small eating place on North Green Street in zip code 28655, I’m consuming food that connects to an entire world of food. What I’m eating and drinking here tonight has links around the globe.

I don’t mean that I’m fascinated by the thought of eating Italian food, or maybe something from a Latin culture or maybe even Icelandic. What amazes me as I sit here and think about it are all the farmers, ranchers, processors, manufacturers, merchants, distributors, and countless other people that make up all the links and combinations possible in a food system that has become amazingly international.

Let your mind wander with me as we select our dinner….

To start…

Okay, I’ll pass on the pre-dinner cocktail. But on a warm summer evening in the south, a Mimosa sure would have been nice. If I had one, I’d be drinking orange juice from Florida. Or maybe Brazil. Brazil exports more than $1 billion in OJ each year – about 10 times what the United States sells abroad. Even some European countries export more orange juice than we do, so who knows where the juice in that particular drink might come from.

But I will have a nice salad. I know this restaurant likes to feature locally produced foods, especially the fresh vegetables that grow so abundantly around here. But when they aren’t available, where does it come from? Maybe California, or Arizona, or Florida. But it also could be from lush fields in Mexico, or maybe Canada. We import cucumbers, tomatoes, peppers, asparagus, onions, squash, and a lot of other vegetables every year, from all across Latin and South America, and even China. If I add fresh and frozen fruit, the list of international suppliers is even longer. It’s a huge part of our food supply picture – about $9 billion each year in vegetables and produce, another $15 billion in fresh and frozen fruits.

I could have a small cup of gumbo to start instead, or maybe some of the fish stew this place is known for. That could include shrimp or bits of fish from across Asia or any number of other suppliers in the northern Atlantic and southern Pacific waters. The chunks of salmon in it might come not from Alaska but farms in the Nordic area. The sea bass could be from Chile. China, Norway, Sweden, Chile, Indonesia, India – all are major fish exporters to the world. We import about 90% of our seafood each year.

The dinner rolls in the basket on the table are made from wheat. I’d like to think the flour originated in the vast fields I’ve seen in the American Midwest. But the world trades just over 180 million tons of wheat each year. (Just for fun I did a quick mental calculation – that would give everyone in the world about 40 loaves of bread) so it must mean that wheat from the United States and a lot of other countries finds its way into bread everywhere. Consumers sitting at restaurants like I am tonight – or at home most other nights — could be eating wheat from Australia, Argentina, Canada, France, or Russia, or any of the 15 countries that account for over 90 percent of global wheat trade. Now the really mind-blowing part…

What should I have as my entrée?

I could go for the grilled salmon. That takes me back to the same international connections I made when contemplating the gumbo and fish stew. Salmon is the most-traded seafood in the world, after all. Almost $4 billion worth of salmon moves in international trade each year, as hungry consumers look for fresh and farmed supplies from Norway, Scotland, Chile, Russia, Canada, Japan, and other sources.

If I go for the nice sirloin on special tonight, I most likely will be eating a U.S.-produced cut of meat. But the Department of Agriculture acknowledges that perhaps 8 percent of our beef supply – and maybe a touch more, according to some — comes from outside our borders, probably Canada or Mexico, or Australia or lean meat from New Zealand.

If I go for the pork medallions, the international picture is even stronger. The United States imported $1.1 billion worth of pork in 2019. (Japan and China together imported over $9 billion worth, out of a global total of pork imports of $32 billion.) Any way you look at it, that’s a lot of pig meat, so I can’t be surprised if some of it winds up on my plate.

If I go for the roasted chicken, the picture is more than a little convoluted. The United States is very good at producing poultry, and we export a lot of what we produce. Poultry is comparatively easy to produce in most parts of the world, albeit sometimes very inefficiently compared to our modern methods. But as much as 12 percent of global poultry meat consumption still depends on trade, according to USDA statistics.

Feeding what kind of mouths?

Which reminds me… the global food system really provides for a lot more than my needs or just human needs.

Our food system has to feed a lot more than human mouths, you realize. Corn and soybeans flow in an almost endless stream around the world to feed the cattle, pigs, chickens and other animals people demand for their tables. More than 70 billion – yes, billion – animals go to market each year around the world, not counting fish and other aquaculture. Corn, soybeans, and other feed grains and oils from the United States, Europe, South America, and other regions around the world keep their food flowing, too. And without that flow, providing the animal protein everyone wants simply wouldn’t be possible. I very likely wouldn’t have the choices available to me on this menu.

But let’s get back to my dinner…

Even the salt and pepper on the table have their global links. The world trades pepper worth over $4 billion each year. The United States is the largest pepper importer in the world, most coming from Vietnam, the largest exporter. If I want more exotic spices – say, those hot peppers I like so much, or even vanilla or oregano or sesame seeds or cinnamon, I have to look to suppliers outside the United States, too. My mind paused as I am now going way back to 130 BCE, thinking of the Silk Road which opened up trade between the East and West.

The global salt trade is even larger, although much of that is used in de-icing and industrial uses, not just for food purposes. The world’s leading exporter of salt is the Netherlands, selling about $278 million worth of salt into export markets in 2018. Germany sold another $206 million, Chile $189 million. This simple staple of life, which I so easily can take for granted, could have originated from 20 different countries, including my own.

The sugar and sweeteners in front of me tell a similar story. Sugar can come from beets or cane and is produced around the world. India and Brazil duke it out most years for the top-producer spot, but the European Union and various sub-tropical countries also contribute to a global sugar trade that normally runs about 55 million tons each year. I am going back to my mental math and figured all that sugar would give everyone in the world 164 cans of Coca-Cola. Demand for sugar is so strong that China still imports large quantities every year, despite being the fifth largest sugar producer in the world (an estimated 10.6 million tons in 2019.)

Even if I grab the Stevia on the table as an alternative, I’m using a product that originates from the leaves of a shrub that grows in Argentina – or even China.

It all makes my head spin. So maybe I’ll skip the dessert, as enticing as the marble cake and its legendary chocolate icing (from cocoa beans that could be grown in Ghana, the Ivory Coast, Indonesia, Nigeria, Brazil, or even Mexico) may be.

Instead, I’ll go for a nice, soothing cup of tea to cap the meal. But do I select a tea grown in India or China? Maybe Japan or Sri Lanka, or Indonesia?

Maybe the main point I should focus on is actually fairly simple. As much as we depend on our local food supplies, for a variety of practical and personal reasons, we live in an inter-connected global food system. The vast majority of the foods we consume every day have some direct or indirect connection to the world of global food trade. I’m really dining OUT!!!

What Trade Makes Possible

How did this happen? Why did we create such a complex and amazingly efficient way of feeding ourselves?

It comes down to economics. International markets assure a steady supply of whatever food we want, whenever we want it, at the best price. It exists so everyone can have exactly what they want, when they want it, without regard for the local growing season or capacity to produce everything such a robust food offering demands. It makes it possible for me to have such an incredible selection of great food, year-round, at affordable prices, right here on North Green Street, or in my home.

We created a marvelous interlocking system of continuous gratification made possible by trade. Trade is the backbone of our modern food system, whether we think about it or not.

No wonder I’m a food junkie. No wonder my head spins. The global food system puts such a variety and quality in front of me every single day. Who could resist?

The Bottom Line

While looking to local food sources is practical and personal, we live in a global food system that is deeply interconnected, and each country and entity plays a role in feeding the world. I bet the next time you dine out, you’ll be thinking, "Man, I traveled much farther than down the block for this delicious meal."

Stalled Trade Deal Threatens U.S. Food System Gains

A carefully negotiated trade agreement between the United States and the European Union could open the door to expanded market opportunities for U.S. farmers and ranchers. But can both sides find a way around the other political disputes that threaten completion of the deal?

Latest in other news...

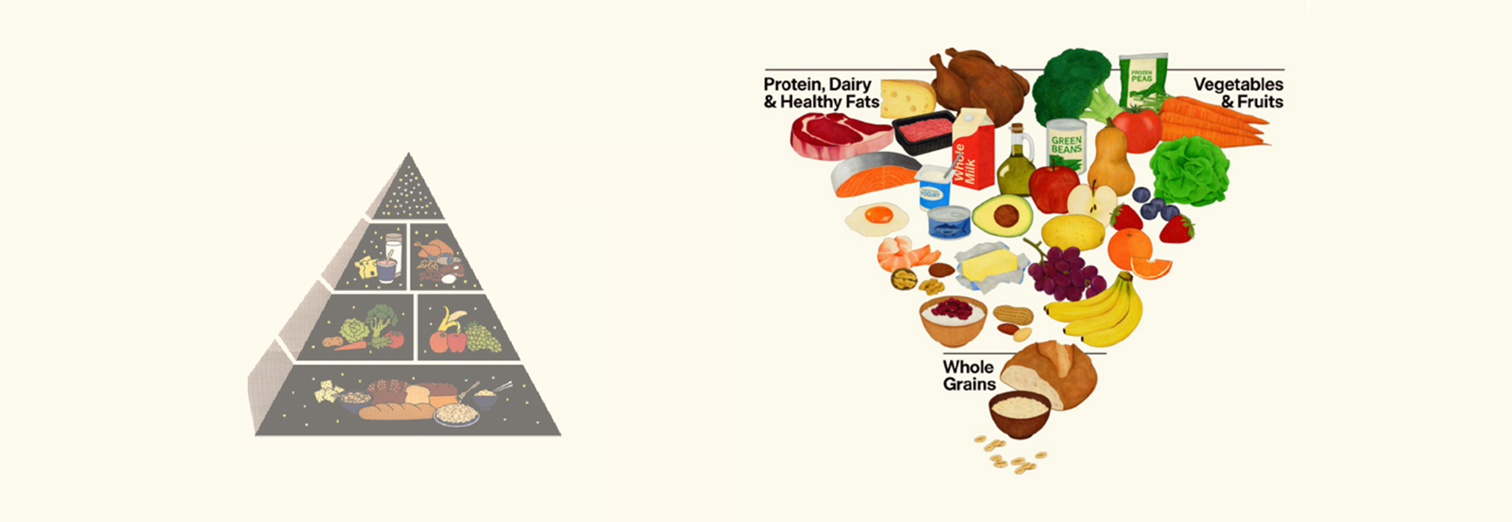

Transcript: The ‘Real Food’ Reset

This is a transcript for the podcast episode, "From Guidelines to Groceries: The Real Food Reset". The new USDA/HHS dietary guidelines marks a “historic reset” in U.S. nutrition policy with a straightforward message: eat real food. But how does this differ from current guidelines?