Energy, Food Costs: The Unexpected Pain of Ukraine Invasion

The Dirt

The world’s attention remains focused this week on the unfolding drama in Ukraine. Many unanswered and unpredictable outcomes for the world regarding geopolitical relationships, energy prices, and grain prices. Most of those questions won’t be fully answered for some time to come. But we do know that while it is uncertain whether the war will have serious immediate consequences for U.S. food consumers, it could have profound longer-term implications for food costs, the global supply chain and the global trading system that makes our modern lifestyle possible.

Global Food

Energy, Food Costs: The Unexpected Pain of Ukraine Invasion

The Dirt

The world’s attention remains focused this week on the unfolding drama in Ukraine. Many unanswered and unpredictable outcomes for the world regarding geopolitical relationships, energy prices, and grain prices. Most of those questions won’t be fully answered for some time to come. But we do know that while it is uncertain whether the war will have serious immediate consequences for U.S. food consumers, it could have profound longer-term implications for food costs, the global supply chain and the global trading system that makes our modern lifestyle possible.

On the run? LISTEN to our post!

For more information on Ukraine’s ag system, check out our recent post, Ukraine: Quiet Pawn in Quest for Food Security

Putin and Russia are being canceled, to say the least. The most immediate and visible effect of the Russian invasion of Ukraine – beyond the awful carnage inflicted on the Ukrainian people – is a massive shift in global international relations. The world is watching Putin try to transform an independent nation into a satellite state loyal to Moscow — a transparent effort to re-establish the model of the old Soviet Union. And the world, except China, is stepping up to defend Ukraine.

The West has been fairly swift in launching a widespread and coordinated effort to inflict economic costs on Russia for its actions. Russia’s exports totaled $39b in November 2021. If every country cancels the bulk of their imports, it would be financially difficult for Russia to survive.

- Restrictions on Russian banking have made doing business more difficult and costly for them, with likely further declines in the Russian ruble.

- Further economic sanctions against the Putin regime and his oligarch cronies will add targeted economic penalties. The EU and the U.S. are even chasing these supporters out of countries where they have their yachts, as well as freezing some of their assets.

- Germany is cutting its dependence on Russia’s natural gas and coal and rethinking the timing of its green carbon-neutral strategy.

- Turkey is limiting Russian ships through the Bosporus from the Mediterranean to the Black Sea.

- A long list of European countries and the U.S. have banned Russian aircraft from their airspace.

- The U.S. banned exports of high-tech goods, such as semiconductor microchips, to curtail Russian defense production.

- Daimler Truck Holding, Volvo Car, General Motors and Harley-Davidson are all reconsidering their business dealings with Russia.

- Apple, Google and Nike, and energy companies such as BP, Shell, Equinor, and TotalEnergies, are starting to pull out of Russia.

- Norway’s sovereign wealth fund is freezing and eventually exiting from its $2.8 billion in Russian assets.

The list grows every day, and the overall effect is to make Putin and his oligarch pariahs in the larger community of nations, and to highlight what many see as a growing international polarization that pits democratic, market-oriented Western economies against the controlled societies built around socialist and communist principles.

As the conflict continues and the world’s attention remains focused on the day-to-day events, average citizens in the United States are likely to see the beginning stages of the consequences of conflict. The most apparent signal will likely come in higher energy costs, notably at the gas pump.

Russia’s top export category is fuel and energy, representing just over half of its total export value of $335 billion in 2020. Imports in May 2021 reached a record 26.2 million barrels, second only to Canadian shipments (over 125 million barrels in May 2021) and ahead of Mexico (22.6 million barrels in May 2021).

By February 2022, Forbes reported that Russia had eclipsed Canada as the largest supplier of imported gasoline for all of 2021. Russia’s Federal Customs Service also noted the United States purchased almost one-fifth of the country’s heavy-oil products, making it Russia’s largest single buyer.

In advance of the invasion, petroleum prices already had peaked above $100 per barrel. As of March 2, the AAA National regular gas price was $3.66 a gallon, up from $2.71 last year. California is now over $5.00 in some spots. Energy experts can’t agree on just how high prices will go – but agree that further increases are on the way.

Source: Forbes, US Gasoline/Energy Imports, 2-24-22.

U.S. efforts to expand domestic energy production could help bring more balance to the supply-demand picture. But expanding domestic energy production will take some time to ramp up and already faces numerous concerns from the green energy group.

Ag in the Energy Crosshairs

Higher energy costs will have a ripple effect across the entire U.S. (and global) economy, and agriculture promises to be among the hardest hit. Energy costs represent as much as 15 percent of total production costs for farmers, according to the Department of Agriculture.

Much of the energy is consumed as fuel for all the various machinery and equipment that drive the efficient production of crops and animals. But another factor becomes especially important for the ag sector: the enormous energy component of the fertilizers farmers around the world depend upon. Rising costs of diesel and gasoline will have an immediate effect on the economics of farming and ranching. But the longer-term implications for fertilizer costs may prove even more serious.

Russia’s major role in global fertilizer markets often goes unnoticed by the average consumer. The country produces and exports petroleum, natural gas and other energy products.

In fact, its leading export category is mineral fuels, worth more than $143 billion each year, or just over 42 percent of all exports.

Russian natural gas is a key source of ammonia that serves as a building block for many nitrogen fertilizers. To add to its prominent role in global fertilizer markets, Russian exports of potash represent 21 percent of the entire global market for the product. (Neighboring Belarus accounts for another 21 percent of potash market.)

The prospect of losing access to these important energy sources concerns the entire ag sector – especially after a year of extraordinary increases in fertilizer costs, even before the threat of invasion fully emerged. Farmers already had seen anhydrous ammonia prices rise by 300 percent, urea by 214 percent and liquid nitrogen by 250 percent over the year before. Potash prices had increased by 213 percent, as well.

Such dramatic increases in energy-related prices – and the prospect of still higher costs to come – can’t be ignored. They threaten significant increases in the cost of production for cornerstone crops such as corn and soybeans, indicating that the food price inflation consumers have seen for the past year is likely to continue. The extent of those inflationary pressures – and the speed at which they spread through the food system – remain the subject of intense debate among economists around the world.

The significance of energy in determining the fallout from the Russian invasion on the average person reflects a bigger truth in modern international relations. We are seeing first-hand just how interconnected all nations have become in a global economy built around a global trading system.

It’s increasingly difficult – and perhaps practically impossible – to function in a vacuum, in which the economic links we have built can be ignored.

A military threat can easily make a normally invisible economic relationship highly visible – and highly important to consumers everywhere. This economic interdependence may offer a powerful tool to resolve the conflict.

It’s all about the trade

The outlook for U.S. farmers and consumers isn’t totally bleak, however. The response to the Russian invasion is built around the significant economic advantages enjoyed by the United States and its allies – and the leverage these advantages can apply to resolving the conflict and restoring more-normal international relations.

The value of Russian exports dipped in 2020, falling from $423 billion the previous year to $335 billion, according to Russian customs data. Statistics also show a mutual trading dependence between the United States and Russia. U.S. imports of Russian energy and minerals create a significant trade deficit in goods. But Russian demand for U.S. services creates a trade surplus that helps offset the deficit.

Overall, Russia remains only the 20th largest trade partner for the United States – and only 40th in terms of the total goods imported into this country.

In contrast, the United States is the sixth-largest trading partner of Russia.

Because we have lost our energy independence, the United States – and the EU – needs Russia’s energy offerings notwithstanding this invasion. But Russia needs U.S. machinery, automotive, aircraft, sophisticated electronics and medical equipment – over $9 billion in 2019, according to the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC). Total imports from the United States reached $13.4 billion in that same year, according to the World Bank. Russia needs and wants what the United States has for sale.

Other statistics suggest the Russian economy needs the West – including the United States – far more than Putin would like to acknowledge. On average, the United States generally imports more from its trading partners than it exports to them – roughly 62 percent imports, to 38 percent exports, according to the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative. However, the U.S. exports far more to Russia than it imports – roughly 82 percent exports, only 12 percent imports.

In other words, Russia needs the United States – and other western markets. The potential loss of trade promises to hit hard on a broad spectrum of Russian interests. (The notable exception is China, which remains Russia’s largest single trading partner.)

How Does U.S. Agriculture Fit into the Picture?

U.S. farmers also stand to benefit from the disruption to key global agricultural markets created by the invasion. Markets for wheat, barley and certain oilseeds may be among the commodities most affected by the invasion and its after-effects.

Russia is the third-largest producer of wheat in the world, with Ukraine rising rapidly in the mix. Together, the two countries also account for more than one-quarter of all global wheat trade and about 70 percent of the world’s total trade in sunflower oil. Ukraine also supplies 13 percent of the world’s corn exports, much of it bound for China, according to USDA. Agricultural export sales from Ukraine have been rising in recent years, climbing to $22.2 billion in 2020. Russian wheat exports mainly go to Egypt and Turkey but the rest of the countries such as Ethiopia, Cameroon, and Kazakhstan will be hard-pressed to afford rising wheat prices.

Trade at-a-glance – 2019 Russia/Ukraine Percent of Global Export Market Share:

- Sunflower Oil: 70%

- Wheat: 25%

- Coal: 14%

- Corn: 13%

- Crude Petroleum: 13%

- Mineral Fuels (coal, petroleum, natural gas): 11%

- Liquified Natural Gas: 6%

Disruptions to Ukraine’s exports of these and other farm commodities could open the door for U.S. growers, especially if restrictions on Russian trade emerge. Rising world prices would help offset the continuing rise in energy and input costs facing the U.S. and other producers. U.S. wheat production and exports have declined slowly in recent years, in part due to significant growth in wheat production around the Black Sea area. The conflict could be the trigger to reverse that trend.

Today, U.S. farmers account for about 6 percent of total world production and 12 percent of export markets. But with wheat prices currently at their highest levels since 2008 and the invasion promising to add fuel to the upward trend, the economic incentive to capture more of the world demand is very strong. Should the conflict expand beyond Ukraine, the risks become even higher.

Increased reliance on the United States as a major source of supply for wheat, corn, oilseeds and other farm commodities also could have another ancillary benefit to the global food system. As the conflict further complicates the regional and global export picture and the associated logistics, the relative stability and continuity of the U.S. food chain might help mitigate further disruptions to the global supply chain.

The U.S. farmer may well prove to be the global food consumer’s best ally in holding the line on further food price inflation.

The Bottom Line

The conflict in Ukraine continues to create more questions than answers for concerned citizens everywhere. But some disruptions to a global food system are inevitable, notably in the flow of several key commodities in the international marketplace on which consumers everywhere depend. The longer the conflict persists, the greater the risk of upward pressures on the prices paid for our food. How much the conflict will contribute to bigger food bills for consumers in the United States and elsewhere can’t be predicted with any degree of certainty.

Latest in other news...

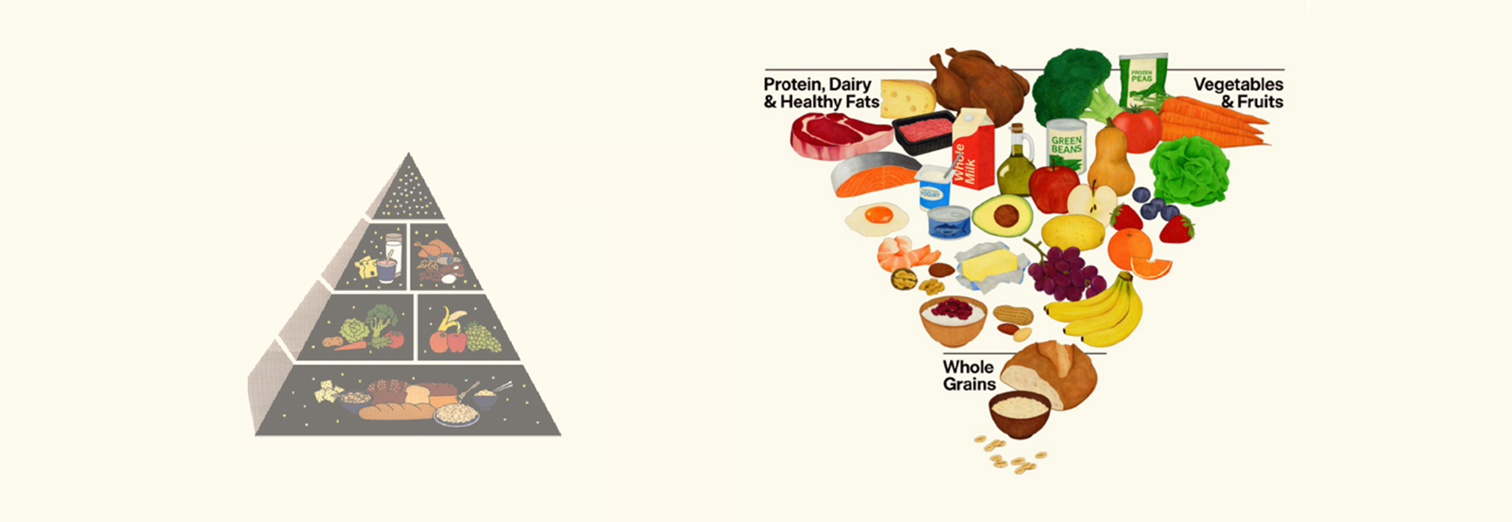

Transcript: The ‘Real Food’ Reset

This is a transcript for the podcast episode, "From Guidelines to Groceries: The Real Food Reset". The new USDA/HHS dietary guidelines marks a “historic reset” in U.S. nutrition policy with a straightforward message: eat real food. But how does this differ from current guidelines?